John Dales and his team at Urban Movement assessed the modern utility of twelve of these period cycle tracks. Urban Movement’s draft findings [PDF] were submitted to the Department for Transport.

The purpose of this Development Project, which has been undertaken in parallel with the research project by Carlton Reid, is essentially twofold: to explore the potential for some of these historic cycleways to serve as valuable parts of the contemporary cycling network; and to work with willing highway authorities to bring forward proposals, backed where appropriate with initial designs, for the improvement and integration of selected cycleways as part of a modern network that meets the standards of provision for cycling set out in Local Transport Note 1/20 (Cycle Infrastructure Design). The key outcome from the work is that local authority officers will be better able to prepare convincing funding bids for design development and the delivery of better conditions for cycling in due course.

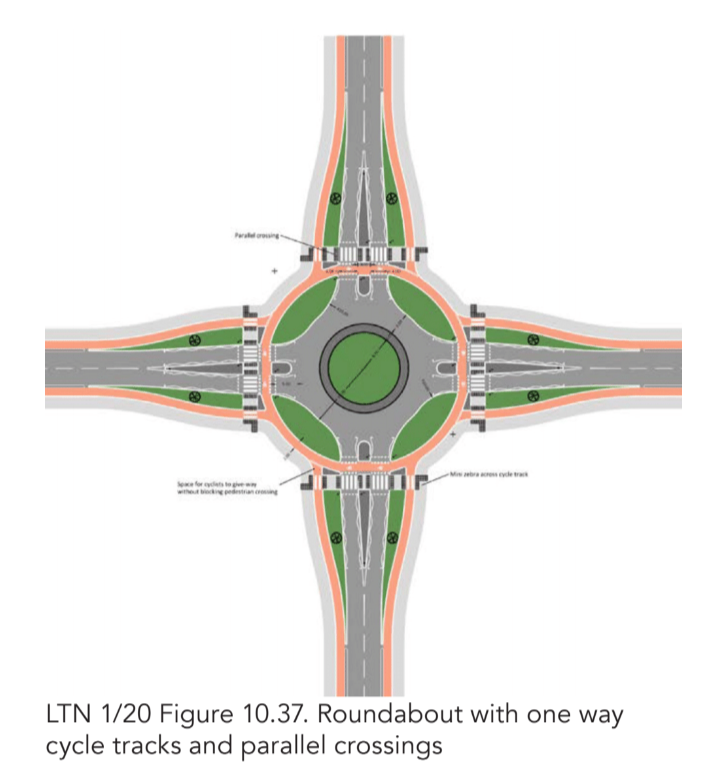

The 1930s cycleways gave a high standard of provision. They were separate, protected and, at almost 3m wide, suitable for bi-directional cycling. Perhaps the key flaw with all the 1930s schemes, however, is that they did not carry priority for cycling through even the smallest junctions. The layout of quiet side street T-junctions are typically bell-mouthed, with large radii that both increase the crossing distance (on foot or cycle) and enable motor vehicles to turn at relatively high speeds. At major junctions, like large roundabouts, the cycleways simply stop altogether, feeding cyclists abruptly into the nearside lane. Another common flaw was that, since they were only constructed as part of a road scheme, the cycleways did not form part of a connected network. Consequently, many of the schemes are relatively short (sometimes less than 1km) and a large number do not connect places between which people might want to travel. Some are alongside bypasses ‘in the middle of nowhere’, while others are in residential areas, but do not link them with any significant employment, commercial or educational centres.

Many of the schemes were built alongside dual carriageways. In such circumstances it is important that cycling is allowed in both directions on both sides of the road. This is because, with crossing the road being difficult and formal opportunities to do so being infrequent, people cannot be expected only to ride ‘with flow’ on one side of the road, against their desired direction of travel, in order to cross to the other side at some point and head back the way they wanted to go in the first place.

Whether or not this was the specific intention, the 9ft width of the tracks enabled bi-directional cycling with reasonable comfort. A variety of historic imagery is presented to illustrate both the way in which the cycleway designs were directly influenced by Dutch precedents and how the schemes looked at or near the time of opening.

PROCESS

The Development Project was undertaken by way of the following three main sequential work stages:

Stage 1. Long-listing of potentially suitable cycleways, based on research by Carlton Reid. This will consider factors including current condition, location, and the relationship (actual or potential) with the other parts of the local cycling network.

Stage 2. Short-listing of the cycleways most suitable for development, through initial discussions with the relevant local authorities. This enabled greater clarity to be achieved concerning the value of the 1930s cycleways in local network-building, and was also a check on the willingness and ability of each authority to commit to pursuing the creation of cycling infrastructure consistent with LTN 1/20.

Stage 3. Preparation of an itemised schedule of improvement measures for each of the selected 1930s cycleways schemes, including – as appropriate – proposals for extending the historic infrastructure to connect better with adjacent parts of the cycling network. Where necessary and helpful, this work was supported by the preparation of concept designs for selected locations.

THE SCHEMES

Links Road — Blyth, Northumberland

The Links — Whitley Bay, North Tyneside

Euxton Lane — Euxton/Chorley, Lancashire

Formby Bypass — Sefton, Merseyside

Harpfield Road — Stoke-on-Trent

Arnold Road — Nottingham

Raynesway — Derby

Melton Road — Leicester

Kenilworth Road — Coventry

Marston Road — Oxford

Uxbridge Road — Hayes, Hillingdon

Mickleham Bypass — Surrey

++++

Links Road, Blyth, Northumberland + The Links, Whitley Bay, North Tyneside

BLYTH

Location: A193 Links Road, Blyth

Original Length: 900m

Authority: Northumberland County Council

WHITLEY BAY

Location: A193, The Links (previously Blyth Road)

Original Length: 800m

Authority: North Tyneside Council

The Blyth and Whitley Bay 1930s cycleways are the second and third most northerly of the schemes so far identified in England. They are somewhat unusual in that, despite being distinct schemes – more than 5km separates them – they are nevertheless both close to one another and are alongside the same road. The road in question is the A193, which runs from Newcastle to Bedlington in Northumberland and, in doing so, follows the North Sea coast from Tynemouth to Blyth via Whitley Bay.

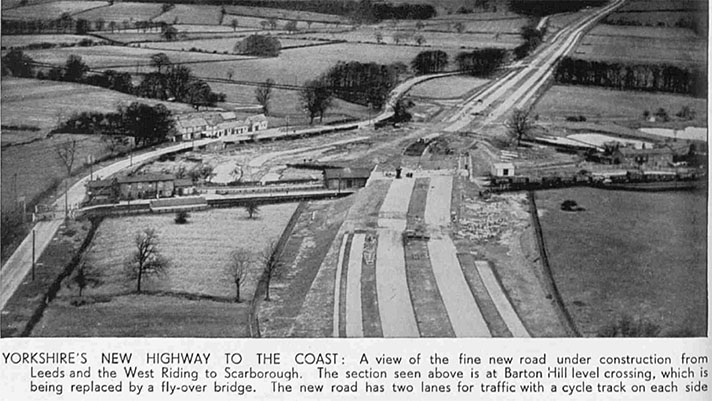

Research has revealed that Blyth Town Council approved plans for the Links Road and its cycle tracks in October 1936. “The Borough Engineer reported … that the proposed scheme was to widen the Links Road to make provision for road 120 feet wide with a two-way motor and cycle tracks, grass verges and footpaths, from the north end of the Promenade to Gloucester Lodge”, said a report in the Morpeth Herald of that year. The layout described was to the standard Ministry of Transport plan of this period for dual carriageways (although the newspaper report said the cycle tracks were to be 10ft wide, whereas the MoT standard was 9ft wide). The Ministry paid 75% of the £31,000 costs.

The relatively short stretch of dual carriageway in question was originally intended to be connected with its almost identical counterpart in Whitley Bay. Vestiges of this planned connection can still be seen: the long, informal linear car park to the east of the A193 north of Seaton Sluice; a stub of road to also to the east of the A193 immediately south of the roundabout junction with the B1325; and a strip of land immediately north of the Whitley Bay Holiday Park, best seen on aerial photos.

However, as with many similar proposals, the new road remained unbuilt because of WWII. According to a report in Blyth News, the dual carriageway, including cycle tracks and footways, was built and operational by May 1939. No comparable reports for the Whitley Bay section have yet been found.

Both schemes are comparatively short, with the Blyth cycleway being in Northumberland and the Whitley Bay section in North Tyneside. The boundary between the two jurisdictions is at the junction of the B1325, on the southern edge of Hartley.

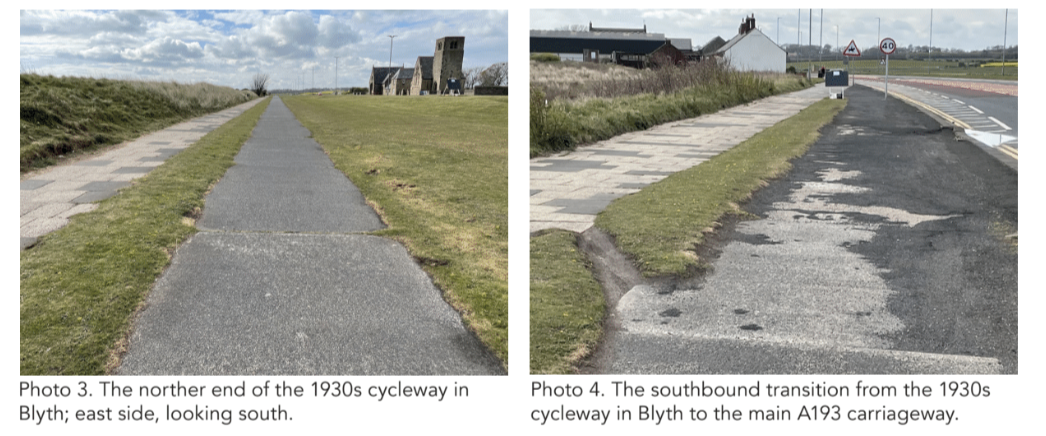

As is characteristic of most 1930s cycleways, both run alongside a dual carriageway and terminate when the road becomes a single carriageway. Both are also virtually intact, on both sides of the main carriageway, and are in a reasonable state of repair. However, both are also like many other 1930s cycleways, in that they never really connected anywhere to anywhere. Partly for this reason, though also for others, observations indicate that the majority of cyclists riding along the A193 where these cycleways exist tend to use the main vehicular carriageway, rather that the separated, protected space provided by the tracks.

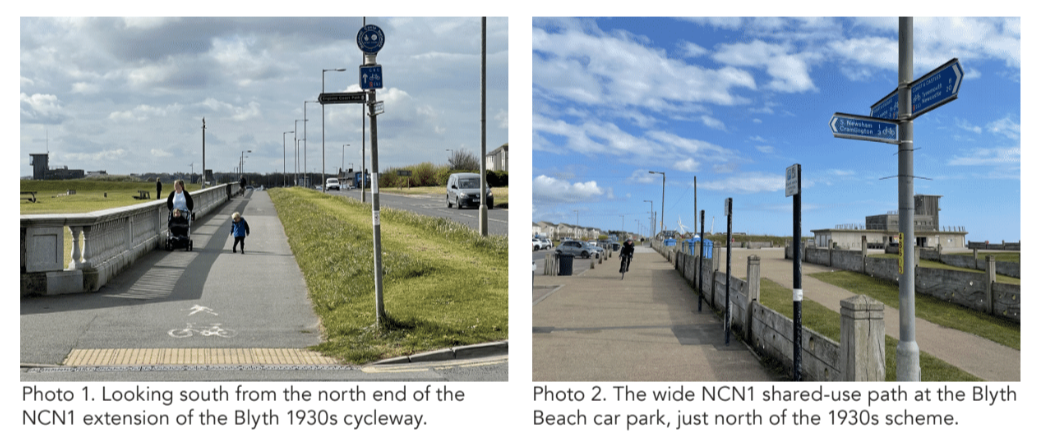

National Cycle Network Route 1 (NCN1) follows the A193 along the coast here, occasionally beingon the A193 itself, but most often (at present) running along parallel off-road paths of different character.

THE CHALLENGES

Both cycleways currently present the generic challenges typical for the 1930s cycleways. As has been mentioned, they don’t connect important origins/destinations and do not currently form part of a cycle link (or wider network) that meets LTN 1/20 standards. Other issues include the physical condition of the surface which, although much better than for many other examples (e.g. there are no major failures, encroachment or tree root damage), is only as good as might be expected from a facility that seems to have been subject to the minimum of maintenance since it was constructed (e.g. sweeping and edge trimmimg).

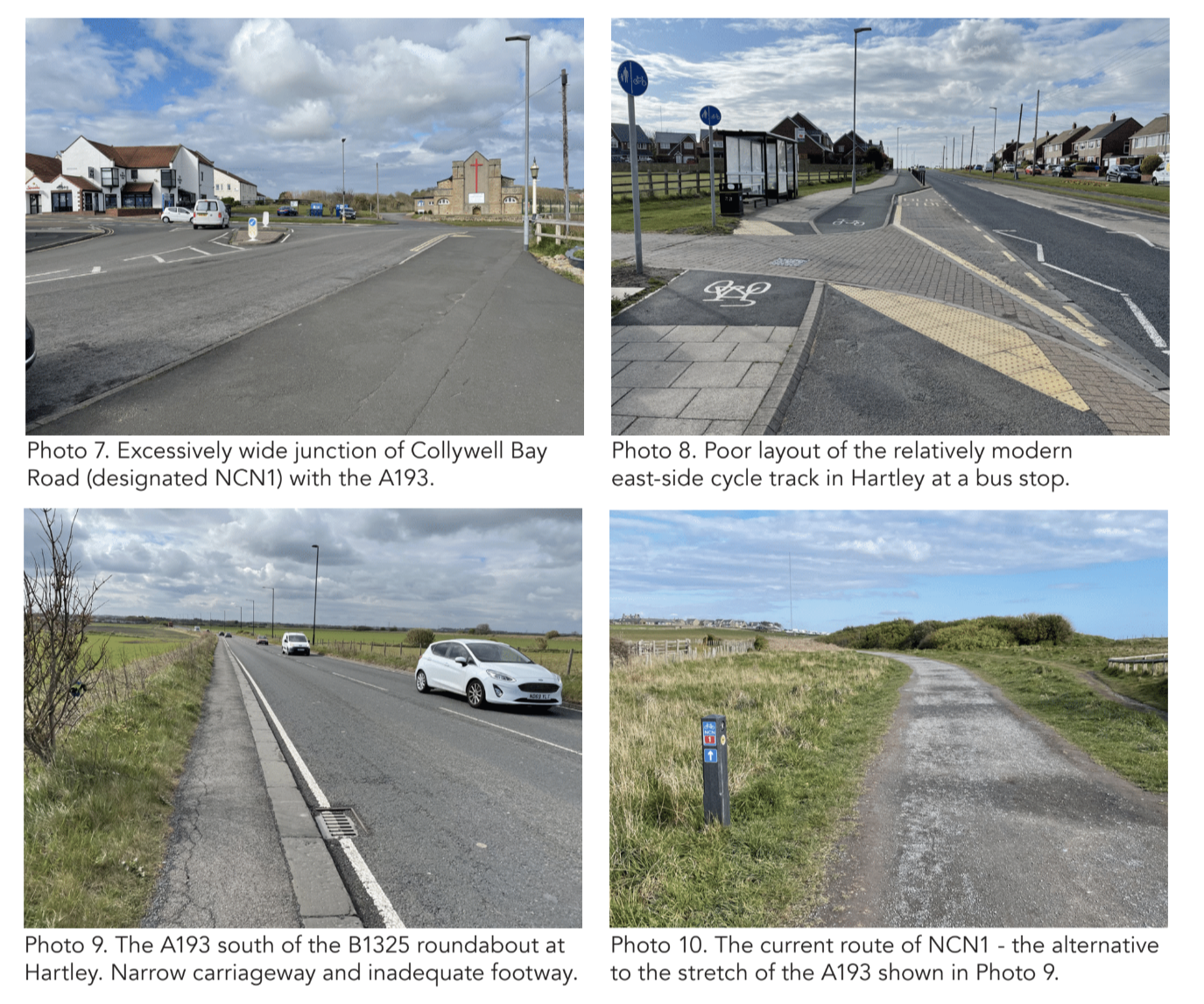

The Whitley Bay section also suffers from the generic challenge found at most side-street junctions on 1930s cycleways, which is that these flair excessively, simultaneously making the crossing distance much greater than it should be and enabling vehicle drivers to make turns in and out at speeds that increase the hazard for people cycling and walking across. Both these user groups are obliged to give way to general traffic when crossing; although there are no formal give way markings, there is no visual continuity of the cycleway or footway across the side street. The principal challenges in connection with developing these two cycleways concern how they can be joined and extended.

However, there seems generally to be enough space within the extents of the (A193) public highway to meet these challenges. While there are one or two pinch-points south of the Whitley Bay section, these could be resolved through modest widening using public space (The Links), not private property. There is one particular section, however, where it is unlikely to be possible to provide high quality cycling facilities in the A193, and this is the stretch from the northern end of the Whitley Bay cycleway to the roundabout junction with the B1325. The current route of NCN1 in this location is largely off-road and passes through a combined Site of Special Scientific Interest, Special Protection Area/RAMSAR, and Conservation Area. However, this challenge can become an opportunity to showcase the latest in environmentally-sensitive surfacing and lighting.

THE OPPORTUNITY

Although they comprise less than a total of 2km in themselves, the Blyth and Whitley Bay 1930s cycleways have the potential to be the catalyst for the creation of a roughly 9km long high-quality cycle route connecting Blyth and Whitley Bay via Seaton Sluice and Hartley. This link would, additionally, connect directly with a roughly 6km long cycleway between North Shields and Whitley Bay, via Tynemouth and Cullercoats, that North Tyneside Council is currently consulting on.

Together, this would represent a 15km-long (nearly 10 miles) cycle track, suitable for all, connecting all the major settlements along the coast in that area, enabling access to the beaches, leisure facilities and other attractions within the SSSI, and providing an LTN 1/20-standard route running parallel to the existing NCN1 off-road facilities (e.g. the Whitley Bay Promenade and Eve Black Way through the sand dunes between Seaton Sluice and Blyth).

The proposal is that the development scheme focuses on the creation of a single, wide bi-directional cycle track between Blyth and Whitley Bay. This would utilise the cycle track on the east side of the A193, although it is proposed that the west-side track in the Whitley Bay section is also developed.

With existing and likely future cycle traffic flows, investing in creating a cycle route on both sides of the A193 is not considered likely to represent value for money for at least another decade. A single, bi-directional track will also be much easier to fit in the section of the A193 south of the Whitley Bay 1930s section, where space is at a premium. The focus on the east side is partly because that is the side visitors to the coast will want to use, and partly because there is no frontage development on the west side of the Blyth 1930s cycleway.

It makes sense also to improve the western side of the Whitley Bay 1930s cycleway, because there is a good deal of residential development on that side, as well as three side street junctions that should not be left in their current state, inhospitable to walking and cycling across.

The possible improvements, both to the 1930s cycleways themselves and to the sections of the A193 to the north, in the middle, and to the south, are summarised as follows:

- Improved off-road link on east side of B1329 Link Road between the Blyth Beach car park and Beachway, including junction improvements to enable transition to the main carriageway for access to Blyth town centre.

- General improvements to the Blyth 1930s cycleway, including de-cluttering through the Blyth Beach car park area, and improved surfacing and widening of the historic facility on the east side of the A193. Including an improved connection with the cycle route to South Newsham and Cramlington, to the west.

- A new, separated bi-directional cycle track formed from re-purposed general carriageway on the east side of the A193, between the 1930s cycleway and Seaton Sluice.

- A new/improved, off-road, bi-directional cycle track formed to the east of the A193/A190 roundabout in Seaton Sluice, connecting with the southern access to Eve Black Way.

- A new, separated bi-directional cycle track formed from re-purposed general carriageway on the east side of the A193, between the southern end of Eve Black Way and Collywell Bay Road.

- Improvements to the A193/Collywell Bay Road junction and to the existing bi-directional cycle track on the east side of the A193 Beresford Road, as far as the B1325 roundabout.

- A greatly improved off-road connection between the A193/B1325 roundabout and via the SSSI and St Mary’s Lighthouse access road.

- General improvements to the Whitley Bay 1930s cycleway, on both sides of the A193.

- A new, separated bi-directional cycle track formed from re-purposed general carriageway, and (at pinch-points) from The Links, between the Briar Dene and the Spanish City plaza.

Euxton Lane, Euxton, Chorley, Lancashire

Location: Euxton Lane, Euxton, Lancashire

Original Length: 1.95km

Authorities: Lancashire County Council (Highway) and Chorley Council

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the installation of the exemplary cycle tracks on Euxton Lane was in anticipation of the influx of thousands of workers that would build the adjacent factory of Royal Ordnance Force (ROF) Chorley. In January 1937, the Lancashire Evening Post reported that “With the coming of a new munitions works to Euxton, near Chorley, some very big problems have to be faced by the Chorley Corporation and Chorley Rural District Council.”

The new factory employed over 1,000 production workers by the outbreak of WWII, rising to 28,000 at the height of the war. Construction of the factory had started in January 1937, with locals complaining about the rowdiness of Irish builders, many of whom housed in ROF Huts at Leyland, an “eight mile area of isolated hutments,” according to the Post in 1939.

Euxton Lane was widened — with footways and cycle tracks included — at roughly the same time as the building of the factory. “It was stated at the monthly meeting of Chorley Town Council… that Euxton-lane, running from the Chorley-Preston main road to the Preston-Wigan road at the Bay Horse, Euxton, and passing the front of the new ordnance factory, is to be a standard width of 80 feet, and will include footpaths, dual carriageways, and cycle tracks,” reported the Post in April 1937. The 80ft width was the Ministry of Transport standard of this period for single carriageway roads, and it would seem that the 1930s cycleways alongside such roads were each just 6ft (1.83m) wide – the same as the footways – not the usual 9ft generally found alongside dual carriageways.

The 1930s cycleways on both sides of Euxton Lane extended from as far west as just east of the railway bridge that is itself just east of Euxton village, to as far east as where the junction with Badger’s Walk now exists: a total distance just short of 2km.

The typical 1930s layout had footways adjacent to the cycleways on both sides, with grass verges between both the main carriageway and cycleway and the cycleway and footway. However, on Euxton Road, this standard layout can only still be found on the north side, between the western end of the scheme and East Terrace. Based on what’s there today, however, it seems likely that the original layout along much of the route may not have been exactly to the standard.

On the north side, from just west of the golf driving range junction to the eastern end of the scheme, and for the easternmost 750m or so of the cycleway on the south side, there is a kerb upstand between the cycleway and footway, not a level grass verge. Elsewhere, and largely due to substantial widening of Euxton Lane either side of the junction with Central Avenue, what were separate footways and cycleways have become single shared use paths.

To the west of the 1930s cycleways, as Euxton Lane passes under the railway bridge, the highway corridor is much narrower than further east, and the physical constraints presented by the railway bridge itself mean that extending high-quality cycling infrastructure along Euxton Lane westwards is, at best, a long-term project.

To the east, there is currently a combination of shared use paths and on-carriageway advisory cycle lanes between the eastern end of the original scheme and the new junction of Euxton Lane with the access to the Strawberry Fields Digital Hub.

East of that junction, there is a narrow shared-use path on the south side of Euxton Lane as far as the junction with the A6 Preston Road.

National Cycle Network Route 55 (NCN55) follows part of the Euxton Lane cycleway, between Central Avenue and the B5252/ Chancery Road roundabout.

On Central Avenue, NCN55 is a good standard (segregated) shared-use path that connects with Buckshaw Village.From the B5252 roundabout, NCN55 run through to Chorley via Chancery Road and AstleyPark.

THE CHALLENGES

The 1930s cycleways on Euxton Lane suffer from three principal problems that are generic for all the cycleways built in that era: they give up at junctions – even those with minor side streets; they do not themselves connect important origins/destinations; and they terminate abruptly without connecting to a wider cycling network of similar standard.

Another important issue is the physical condition of the surface. On the sections that have not been converted to shared-use paths in the relatively recent past, very few traces of the original concrete surface remain visible. However, the present surface – often what seems to be a fairly basic asphalt covering – is in a variable state of repair and does not provide a comfortable riding experience. This is in part because of general failures arising from poor maintenance, but is also due to encroachment by vegetation (the grass verges and adjacent shrubs/hedges) and occasional damage caused by tree roots.

Two particular large junctions need treatment, these being the signalised T-junction of Euxton Lane with Central Avenue (which links with Buckshaw Village) and the roundabout junction with the B5252 West Way and Chancery Road.

At the former, the cycling route along the north side of Euxton Lane is by way of a staggered signalised crossing over Central Avenue which is shared with pedestrians and involves a ‘sheep pen’ island of modest dimensions. At the B5252 roundabout, the connection between the north-side cycleway and Chancery Road (the current route of NCN52) is via a two-part uncontrolled crossing of the eastern Euxton Lane arm, with both parts (either side of the central reserve island) being two lanes wide. This is far from inviting for people on cycles.

Other challenges involve improving or creating connections between the historic cycleway and the wider network. These range from short-cuts through hedges between the cycleway and residential streets at the west end of the scheme to improvements to the quality of facilities on the eastern part of Euxton Lane, between the end ofthe historic cycleways and the A6 Preston Road.

THE OPPORTUNITY

While there is little practical scope, in the shortor medium-term, for extending the historic cycleways west to connect with Euxton village itself, there are many more opportunities along the old scheme itself, and further east.

One opportunity concerns the substantial residential area (around 250-300 houses?) on the north side of the western end of Euxton Lane, accessed by Wentworth Drive and Mile Stone Meadow. It is essentially a large cul-de-sac (collection of small culs-de-sacs) bounded by two railway lines, a business park, and Euxton Lane. This area has no direct connections to any local retail, leisure or educational facilities, and – with all properties having their own parking spaces just outside the front door – it is likely that the great majority of even the shortest trips beyond the area (all of which must go via Euxton Lane) will be undertaken by car. Yet, a large number of shops, services and employment opportunities, as well as the Trinity Primary School and Buckshaw Parkway station, are now within 1 to 1.5 miles in Buckshaw village. Runshaw College is even nearer.

Access to many attractions in Buckshaw Village is more direct by cycle than by car, as there is a shared-use path on the east side of Central Avenue, some 150m south of the Buckshaw Avenue roundabout, which is the nearest access point for motor traffic.

Comparatively modest improvements at junctions, together with the creation of a small number of new, very short, direct walking/cycling connections between the historic cycleway and adjacent sites (e.g. the College, GymWorks, and one or two of the culs-de-sac) could transform the attractiveness of cycling (and walking) for these short, everyday trips.

The Euxton Lane cycleway also forms the core element of what could be a high-quality cycling route between Buckshaw Village (and Euxton Village) and the Chorley and South Ribble Hospital. Although the historic route terminates around 600m west of the main hospital entrance, and around 800m west of the junction with the A6, there is a shared-use path on the north side of Euxton Lane as far east as the new access to the Strawberry Fields Digital Hub, and on the south side of Euxton Lane for the full distance between Badger’s Walk and the A6. (Somewhat curiously, there is also an advisory cycle lane in the main carriageway, in both directions, between Badger’s Walk and the Strawberry Fields junction.)

Both of the shared use paths could be appreciably improved in terms of the level of service they provide to people both walking and cycling, at relatively low cost and with minimal effect on general traffic capacity.

Bearing in mind current and likely future levels of use, and the importance of ensuring value for investment, it is recommended that the emphasis of works to improve the historic features should be on creating a high-quality bi-directional cycle track on the north side. The north is preferred to the south on the grounds of there being a greater number of destinations on the north side: Buckshaw Village and station, the College and the Wentworth Drive residential area. The south side is not to be ignored, however, there being on that side new homes around Stansfield Drive (to the west) and Mimosa Close (to the east), and the existing alignment of National Cycle Network route NCN55, which currently runs from Euxton Lane to central Chorley via Chancery Road and Astley Park.

On the south side, though east of the historic scheme, there is also the Chorley and South Ribble Hospital. Extending the benefits in terms of adding real value to any upgrade of the 1930s cycleways on Euxton Lane themselves, the obvious opportunity is to improve the quality of cycling facilities on the easternmost 800m of Euxton Lane, connecting past the hospital to the A6 Preston Road.

In due course, conditions for cycling could also be improved on the 1.5km route between the Euxton Lane/A6 roundabout and Chorley town centre, via the A6/Preston Road and A581/Park Road. The current designated cycle route between Euxton Lane and Chorley town centre is via NCN55, which runs along Central Avenue past Buckshaw Village, part of Euxton Lane, and then via Chancery Road and Astley Park. While this route is acceptable for low volumes of leisure cycling, it is far from direct and the narrow shared-use path on Chancery Road creates conditions that are comparatively poor for people both on foot and on cycles. Moreover,the route through Astley Park is not well-lit and cannot be considered suitable for everyday cycling throughout the day and year.

It is understood that improving cycling conditions on the Preston Road-Park Road link has been explored relatively recently, with the conclusion having been reached that traffic capacity concerns would make it difficult to introduce good quality cycle facilities on the A6 section in the short-term.

There is some existing provision for cycling on Park Road: shared-use paths on both sides of between the entrance to Astley Park and Rectory Close; advisory cycles lanes on both sides between Rectory Close and Commercial Road; a northbound advisory cycle lane Commercial Road and the A6. There is clear scope and opportunity to improve the quality of these facilities in line with Local Transport Note 1/20.

On the A6/Preston Road section of the route, there is currently only a southbound advisory cycle lane on part of it. There is scope for much better, however, and options to improve cycling facilities on this stretch can be developed in the light of the Government’s Net Zero Strategy, Lancashire’s Climate Change Strategy (to 2020), and Chorley Council’s pledge to work to make the Borough carbon neutral by 2030.

A full schedule of possible improvements, principally to the 1930s cycleways themselves but also to the easternmost 800m of Euxton Lane, is summarised as follows:

- On the north side, between the western end of the 1930s scheme and East Terreace, re-use the available space (about 7m in total), to create a 2m footway and 3m bi-directional cycleway, separated by a kerb step or a 0.5m grass verge. Maintain a 1.5-2.0m grass verge between the cycleway and main carriageway. Modify junctions with Wenworth Drive and East Terrace to provide walking and cycling priority across, as per LTN 1/20. Remove bus stop layout.

- On the north side, between East Terrace and Central Avenue, in the short term improve the ‘segregated shared’ arrangement by installing a tactile delineator strip between the footway and cycleway. In the long term, remove the dedicated left turn general traffic lane and reuse the space to provided separate, protected footway and cycleway.

- On the south side, between the west end of the 1930s scheme and Central Avenue, re-use the available space (about 7m), to create a 2m footway and 3m bi-directional cycleway, separated by a kerb step or a 0.5m grass verge. Maintain a 1.5-2.0m grass verge between the cycleway and main carriageway.

- Modify the Euxton Lane/Central Avenue signalised junction to reduce vehicle speeds on turns and create wider islands on both north and west arms to enable comfortable straight-ahead (though still two-stage) crossing by people walking and cycling.

- On the north side, between Central Avenue and the West Way/Chancery Road roundabout, modify the existing layout to provide separate 2m footway and 3m bi-directional cycleway. Modify side junctions to provide walking and cycling priority across, as per LTN 1/20. Modify bus stop layouts as necessary.

- Replace the informal crossing of the east arm of the West Way/Chancery Road roundabout with a two-stage Toucan crossing; widen the central island (narrowing eastbound exit lane); and renew the ‘segregated shared’ path through the crossing.

- Between the West Way/Chancery Roadroundabout and the eastern end of the 1930sscheme, on both sides, resurface/repair/widen the cycleway (3m), footway (2m) and separatingkerb step; cut back encroaching vegetation. Between Badger’s Walk and the new signalised junction with the Strawberry Fields business park, reuse the existing shared-use footway on on-carriageway advisory cycle lane space (around 4.5m) on both sides to create a 4m shared-use path with a 0.5m grass verge and kerb separating from the main carriageway.

- Remodel the Strawberry Fields business park junction to provide much better facilities for people walking and cycling.

- Between the Strawberry Fields business park junction and A6 roundabout, focus attention on achieving the best possible walking and cycling facilities on the south (Hospital) side, repurposing a general traffic lane, if necessary to create LTN 1/20-compliant conditions.

Formby Bypass, Formby, Sefton

Location: A565 Formby Bypass, Formby, Sefton, Merseyside

Original Length: 6.15km

Authority: Sefton Council

The dual carriageway bypassing Formby was opened with great civic pride at midday on Saturday, December 17th 1938. The bypass was considered such a marvel that Lancashire County Council produced a 16-page commemorative brochure for the opening, at which the Earl of Derby, Lord Lieutenant of Lancashire, gave a ribbon-cutting speech to a “large assembly.” Alderman P. Macdonald, the vice-chairman of the County Council’s highways committee, said the bypass was “laid out on the most modern lines and constructed according to the requirements of the Ministry of Transport”. Indeed, it was the Ministry that stipulated that the road should have cycle tracks, it having been initially planned in 1928 as a narrower road without them. Interestingly, a traffic census conducted on the old road – the findings of which were included in the brochure – counted 530 cyclists in 1928, and 2,291 in 1938, a four-fold increase. In the same period, motor-car use had only doubled.

Reported in the Formby Times on the day of opening, Macdonald said the bypass has “two carriageways with a central reservation and a cycle track on either side, along with a good footpath.” He added, “By this segregation of traffic (I hope) that accidents will be reduced, that the flow of traffic will be facilitated, and the comfort of users will be added to.”

The brochure describes the near four-mile-long road as 120 feet wide with dual carriageways 22 feet wide. There was also a central reservation of 22 feet and “cycle tracks nine feet wide and footpaths six feet wide, with grass margins.” The brochure also stated that the bypass cost £195,483, “towards which the Ministry of Transport indicated a grant of 60% on 17th April, 1936.”

Work commenced on April 9th 1937 and the bulk was completed by September 1938. The brochure is a treasure trove of construction details.

“The near side kerbs joining the cycle tracks are 10 inches by four inches and are laid directly on the extremity of the concrete carriageway slabs.”

The cycle tracks were constructed with “6 inches consolidated foundation of clinker ballast covered with a binder course of tarmacadam [one and a half] inches thick over which is laid a [three-eighths inch] layer of sand carpeting, squeegeed with bituminous compound and covered with [threesixteenths of an inch] gauge green chippings evenly distributed and lightly rolled to produce a matt, non-skid surface finish.

“The near-side concrete kerb of the cycle tracks is set sufficiently low to prevent cycle pedals from coming into contact with it. And the offside timber kerb is fixed flush with the surfaces of the cycle track and adjacent grass margin so that it can be overrun in the case of an emergency.

“The footpaths are constructed in a similar manner to the cycle tracks, except that the foundation of clinker ballast is three inches thick and the squeegeed surface of the sand carpeting is covered with half inch gauge pink chippings.”

The Formby bypass is one of several roads with adjacent cycle tracks constructed in Lancashire in the 1930s. Indeed, in the 1930s and through to the 1950s, Lancashire was the most active road-building county in the country, chiefly due to the initiative of Sir James Drake, the County Surveyor.

The council’s Preston Bypass, opened in December 1958 and long advocated by the then-retired Drake, was Britain’s first motorway.

The 1930s cycleways ran north-south for over 6km from the junction with Southport Old Road – just south of what was the Chesire Lines Railway corridor and what is now the alignment of Moor Lane and Coastal Road – to a point a little south of North End Lane/New Causeway.

At the south end, in a manner typical of 1930s cycleways, the cycleway simply peters out in the middle of nowhere. Accordingly, the focus of this initiative is on the northernmost 4.9km of the scheme, as far south as far south as the roundabout junction with the B5424 Liverpool Road.

A great deal of new development has happened and is happening in that southern section, and this is one of the reasons why bringing the 1930s cycleways back to life has such potential.

THE CHALLENGES

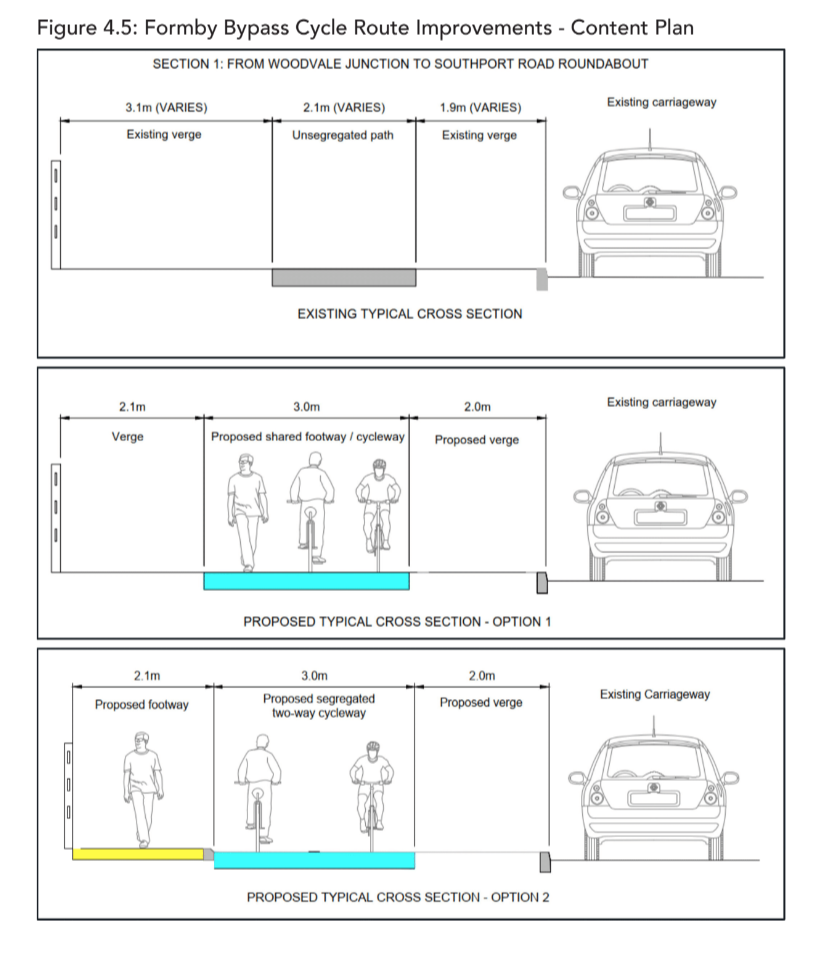

As described above, the original layout of the cycleways and footways adjacent to the bypass was as per the Ministry’s highest standard: a 6ft footway and 9ft cycleway on each side, separate from one another and the main carriageway by grass verges. However, today, there is only one short section where both the footway and cycleway can separately be seen – for about 320m on the west side, immediately north of the entrance to RAF Woodvale.

The dual carriageway and central verge have not been widened materially, however, it is simply that, over time, the separate footway, cycleway and verges (totalling around 7m) have become merged so that there is now, on both sides of the road, just a single shared-use path around 2.5m wide with very generous grass verges either side.

The Formby cycleways also suffer from two of the classic flaws of the 1930s schemes: they never formed part of a coherent cycling network and, at the southern end at least, they simply stop in the middle of nowhere. Like many other 1930s schemes, the Formby cycleways were not built to serve any specific places where people might want to cycle to or from – they were just created either side of a new road.

And given this the road was a bypass, its chief purpose was to avoid places where people were.

Because the original foot and cycleways have been so modified, and also because of their extra-urban location, another common flaw – that of poor physical condition, often compounded by tree root damage – is not a major issue. That said, being alongside a busy, high-speed road (60 mph) means that the existing paths are subject to being sprayed with gravel and other fine material.

Lamp columns present a possible impediment to widening. The character of the location also means that cycling alongside the Formby bypass is not badly affected by numerous interruptions at side streets (the design of which is another classic problem). However, in common with seemingly every other 1930s scheme, the cycleways simply terminate at major junctions, directing cyclists into the main carriageway. People on foot – several of whom were observed on a site visit – simply have to manage as best they can.

THE OPPORTUNITY

In many respects, it might be thought surprising that there is any meaningful opportunity here. What would be the point of improving cycleways on a bypass located away from where people live and work? Well, there wouldn’t have been a point a few years ago, but times change. A large number of homes have been and are being built immediately adjacent to the A565, and more are planned. Other destinations have also cropped up in recent years, including a Tesco superstore and adjacent employment area on the east side of the junction with Altcar Road. As a result, Sefton Council has already begun to develop plans to improve the quality of the historic cycling facilities alongside the Formby Bypass, to enable people to travel to and from such origins and destinations as these.

Improvement plans are proposed to begin at the north and work south in successive stages. In addition to serving recent and new development, these improved cycling and walking facilities also present the opportunity to upgrade the National Cycle Network.

The existing NCN810 runs roughly parallel to and 1km west of the A565, while just a very short extension at the the northern end of the 1930s scheme would enable it to connect with NCN62.

However, north of Formby, NCN810 is unlit and there is a rough track that is in poor condition for much of the year.

A new route from Formby town centre via part of the 1930s scheme would provide better 24/7/365 connection between NCNs 810 and 62.

Developed by consultants for Sefton, there are two given options for upgrading the cycleways in northern section, and these are also applicable further south. Work is also in hand to create the short link at the north end to NCN62, and to explore significant improvements to the small number of major junctions.

Hilton Road + Harpfield Road, Stoke-on-Trent

Location: Hilton Road and Harpfield Road, Stoke

Original Length: 1.4km

Authority: Stoke-on-Trent City Council

Not a great deal is yet known about the history of the cycleways on Hilton Road and Harpfield Road, beyond that they were installed some time after 1935. In September of that year, the *Staffordshire Sentinel reported that: “Following a letter from the Ministry of Transport stating that the Minister had decided to make available increased grants for works of improvements on Class 1 roads where the provision of dual carriageways and cycle tracks was made, the Highways and Plans Committee recommended that the Ministry be informed that, in connection with the scheme already submitted for the 80ft Harpfield bypass road, the committee were prepared to consider proceeding with the full width construction, including dual carriageway and cycle tracks.”

In keeping with many other 1930s schemes, Hilton Road and the section of Harpfield Road that has original cycleways are dual carriageways. However, they are comparatively narrow examples of this layout, and the central reservation is generally only 1m wide. Indeed, 80ft was generally the standard Ministry of Transport width of a single carriageway road at the time. Accordingly, it would seem, the cycleways in Stoke are each just 6ft (1.83m) wide – the same as the footways – not the usual 9ft. Plainly, this will have an effect on how they might best be developed to form part of a high-quality contemporary cycling network.

In both the Hilton Road (north) and Harpfield Road (south) sections, the carriageway on each side of the narrow central reservation is around 6.1m (20 ft) wide. This is enough for two running lanes in each direction, but the space is now generally laid out as nearside parking lane and a single running lane (around 3.8m wide).

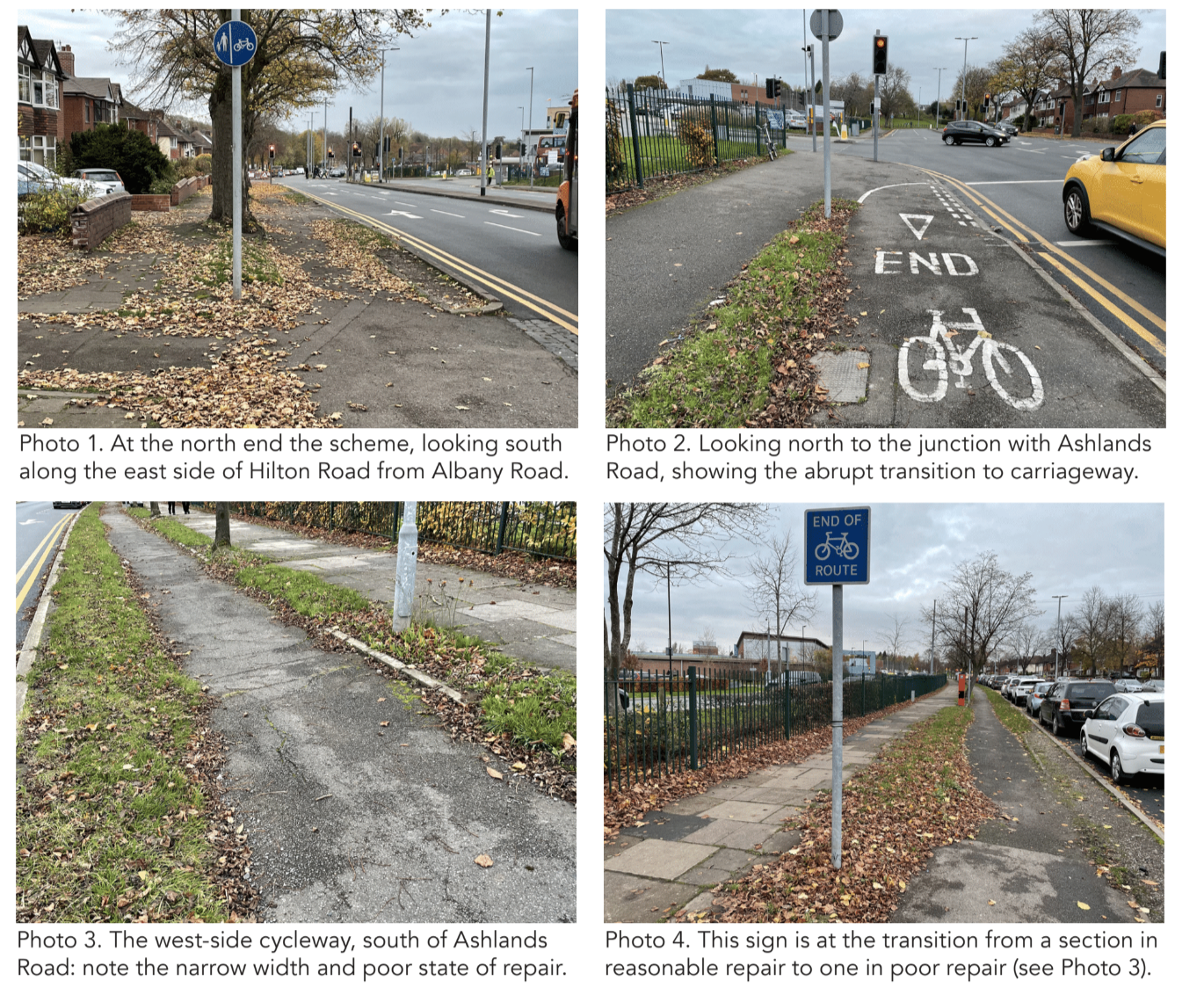

The northernmost part of the scheme is on Hilton Road, roughly 80m north of its signalised junction with Ashlands Road (east arm) and the access road around the north of the Royal Stoke University Hospital (west).

As things are today, Hilton Road simply becomes Albany Road at the point, going north, where the street narrows to a single carriageway.

Historic mapping shows, however, that Hilton Road previously extended a little further north to a junction with Albany Road, Longfield Road and another street called Broadway (now Fosbrooke Place). North of Ashlands Road, the cycleway is now absent on the west side of Hilton Road. South of that junction, however, the historic layout is present on both sides of the road.

The quality of the surface varies considerably. Between Ashlands Road and the roundabout junction with Newcastle Lane, the land use on the west side of Hilton Road is related to the hospital in one way or the other, be that medical facilities, staff accommodation, or car parks.

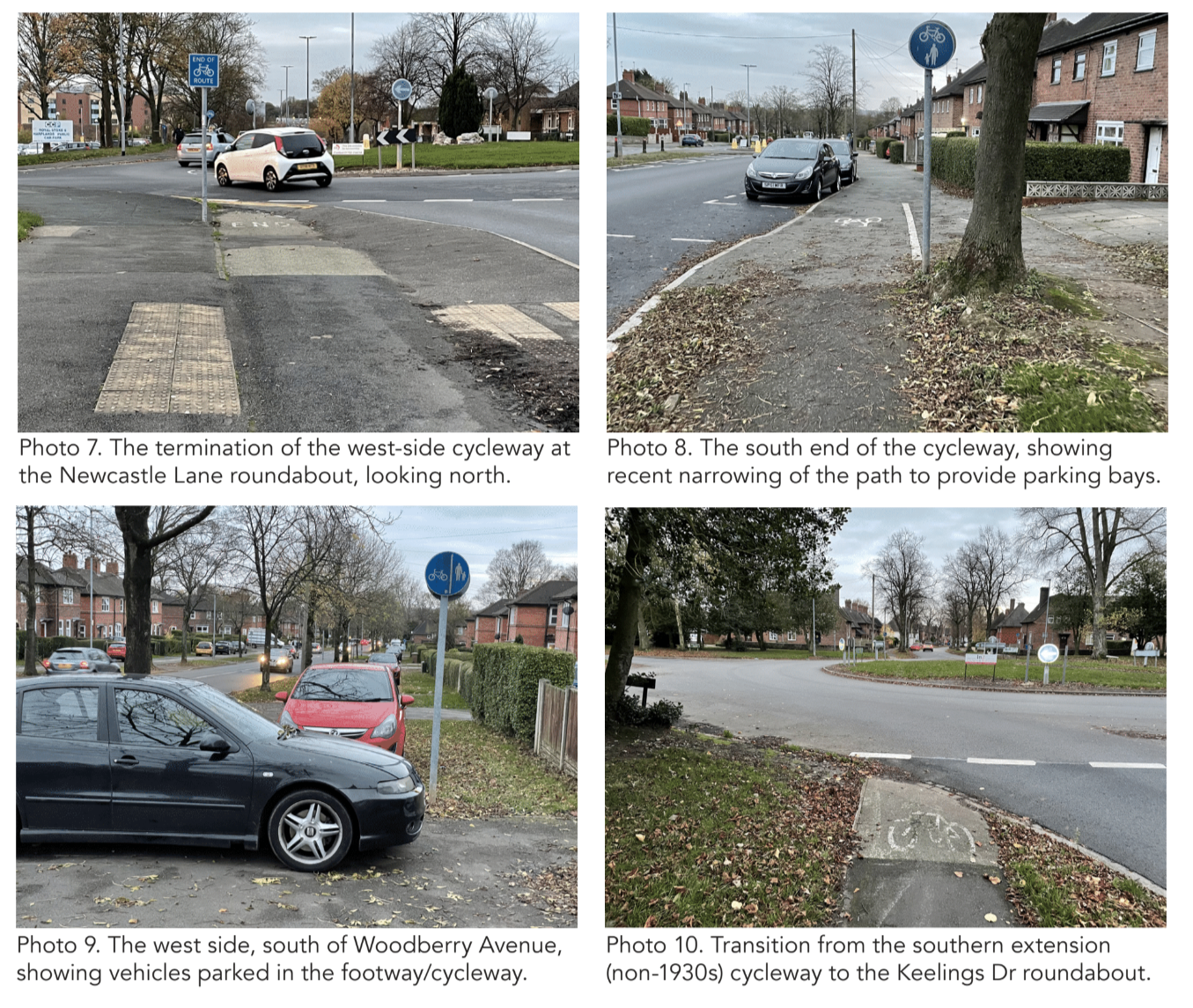

The east side, by contrast, is predominantly residential, and this brings with it issues related to vehicular access to domestic forecourts. At the Newcastle Lane roundabout, as is characteristic of the 1930s schemes, the cycleways simply terminate with short ramps to/from the main carriageway. There is clearly space, however, within which to create a layout that gives much greater protection and priority to both walking and cycling.

Newcastle Lane marks the division between Hilton Road and Harpfield Road, and the 1930s scheme on the latter extends approximately 630m further south, to the junction with Woodberry Avenue (east side). Unfortunately, the southernmost 70m of the west-side cycleway was destroyed, some time between 2015 and 2018,by carriageway widening undertaken to create a nearside parking lane.

Between Woodberry Avenue and the six-arm Keelings Drive/Withies Road/Sutton Drive roundabout (approx 350m), Harpfield Road is a two-lane a single carriageway, with cycling and walking provided for by a roughly 3.5m-wide ‘segregated shared-use’ path on each side.

The highway is around 24m between property boundaries. The paths are separated from the carriageway by a roughly 3m-wide grass verge that also contains trees at approximately 12-15m centres, and there is also a grass verge between the paths and the property boundaries.

Parking seems commonplace in the path on both sides, as well as in the planted verge.

Between Keelings Drive and the A34 Newcastle Road/Flash Lane junction (around 325m), there is also a ‘segregated shared-use’ path and tree-planted verge on both sides. The overall highway width is narrower (around 20m), however, and this means that the paths are somewhat narrower than further north, too (no wider than 3m).

The absence of a grass verge between the paths and the property boundaries further reduces the effective width of the ‘segregated shared-use’ paths, which are hard up against boundary walls.

Flash Lane forms a junction on the east side of Harpfield Road immediately north/east of the junction with Newcastle Road where Harpfield Road ends.

A narrow bi-directional cycle route is marked in paint on the spur of footway between Flash Lane and Newcastle Road, and this connects with a roughly 3m-wide cycle path (signed as shared-use) that runs through a grassy space for around 50m to reach a Puffin crossing of Newcastle Road. It is here that the cycle route along Hilton Road and Harpfield Road can be said definitively to have its southern end.

THE CHALLENGES

One of the chief drawbacks in seeking to develop the 1930s cycleways on Hilton Road and Harpfield Road is that fact that they were originally 6ft wide, the same as the footways,not the 9ft common with other schemes. This means that they are too narrow to be used for bi-directional cycling, which would usually be considered best in the context of a dual carriageway. That said, with there being only a single running lane (plus a parking lane) on each side, a 30mph speed limit and a very narrow central reservation, and numerous breaks, it is comparatively easy for people on cycles to cross from one side to the other. Other challenges are typical of many other 1930s-era cycleways: a rough/broken surface (due to general lack of maintenance and tree root damage); narrowing due to encroachment of the grass verges; and lack of sweeping.

There are also the classic issues of numerous poorly designed side street junctions and of the cycleways simply giving up at major junctions. There are three of the latter: the signalised junction at the north end with Ashlands Road; the central roundabout with Newcastle Lane; and the roundabout with Keelings Drive to the south of the 1930s scheme.

As for side streets and other side accesses (e.g. for car parks), there is a total of eight junctions within the historic scheme where walking and cycling priority across is a problem. Previous attempts have been made to address this problem, with the cycleway marked in green across the mouth of some junctions, and give way markings behind this marked path on exit from some side streets. However, the basic geometry – the mouths of the junctions being too wide and turn radii too large – remains an inherent problem.

A further five such junctions between the southern end of the 1930s scheme and the A34 Newcastle Road.

The link between the south of the original scheme and the A34 is itself another challenge. There are currently walking and cycling facilities on both sides of this narrower, roughly 700m-long single carriageway section. However, they are in the form of ‘segregated shared-use’ paths that provide a poor level of service for all users. Moreover, there seems to be much greater demand for residential parking on-street in this southern section, and this will also be a challenge to resolve.

THE OPPORTUNITY

One of the problematic characteristics of many 1930s schemes is not a problem with the Stoke scheme: that of the cycleways being in the middle of nowhere and/or not connecting any important destinations. In this case, the cycleways not only run through a large residential area but also link it with the Royal Stoke University Hospital (at the north end of the scheme) and a number of satellite health facilities, and with a large employment area, a few hundred metres south of the junction of Harpfield Road with the A34.

Even though the latter is dominated by several large distribution warehouses, it is nevertheless home to many jobs, as – of course – is the hospital.

At all three of the large junctions along the route (including the Keelings Drive roundabout which is south of the original scheme), there is ample space to modify the existing layouts to create much better conditions for walking and cycling.

The Newcastle Lane roundabout could, for example, be remodelled. In addition, due to comparatively low traffic speeds and volumes, the constraints on improving side street and car park junctions are minimal.

There is also the simple fact that the space occupied by the original cycleways, footways and verges has not been encroached upon to any significant extent as a result of any carriageway widening or other measures. Some of the bus stop arrangements need to be modified, but there are no physical limitations on doing so. Moreover, there is a great deal of on-street non-residential parking, along Hilton Road in particular, and some of this could be repurposed should the space be required for other uses such as build-outs for crossing points, bus stop facilities, or even cycleway widening. Extending the Benefits There is plainly a promising opportunity to connect the 1930s cycleways south from their original end-point near Woodberry Avenue to the A34.

As stated above, to achieve high quality cycling and walking conditions on this stretch will not be without its challenges, but there is scope to make an appreciable difference.

While the grass verges with often fine mature trees should generally be considered a fixed constraint, some protected space for cycling (in one direction) could be reclaimed from the carriageway, and the ‘segregated shared-use’ paths on either side could be improved to provide a much better level of service than currently. They could be widened to their maximum extent, relaid by machine to create a smooth surface, and provided with better transitions to/fromnthe carriageway.

If maintained as ‘segregated/shared-use’, the segregation should be provided in the form of a regulation tactile delineator strip, not just a painted line.

At the southern connection with the existing cycling facilities on the east side of the A34, a new parallel foot/cycle crossing should be provided just to the north of the side junction with Flash Lane, while that junction should be narrowed substantially to reduce vehicle speeds and create shorter crossing distances.

Further works to improve cycling facilities along the A34, linking to the employment area, should be pursued in due course.

Arnold Road, Nottingham

Location: B6004 Arnold Road, Nottingham

Original Length: 1.2km

Authority: Nottingham City Council

The 1940s aerial layer of Nottingham City Council’s Insight Mapping shows the cycleways and footways beside the Arnold Road dual carriageway. They were probably installed sometime between 1937 and 1939 when the City Council built several stretches of cycleway alongside a number of Nottingham’s arterial roads.

According to the Nottingham Evening Post in 1937, the “first highway [in Nottingham] to incorporate separate cycle tracks on each side is now in course of construction, and considerable progress has been made.”

The highway in question was Middleton Boulevard, linking with University Boulevard.

“It is anticipated that the present section… may be completed by next summer, and the distance from Dunkirk to Mansfield-road, via Western-boulevard and Valley-road will be five miles,” said the report.

“The special cycle tracks, which the Ministry of Transport insisted upon,” the Post added, “will be 9ft wide, and will be separated from the footpaths and carriageways by grass strips 5ft 6ins wide. Footpaths will be 10ft wide, and the dual carriageways 20ft in width, divided by a central grass plot of similar dimensions.”

Unlike Middleton Boulevard, however, the 1.2km section of Arnold Road alongside which separate footways and cycleways were constructed is, and has always been, a single carriageway. Although the basic layout visible today is very familiar from other 1930s schemes – a parallel footway and cycleway on each side of the main carriageway, and grass verges separating the cycleway from both the carriageway and footway – it would appear that the original dimensions of the cycleway and footway may not have been the standard 9ft and 6ft. Much may have happened in the past 80 or so years to modify the original layout, of course, but the widths visible today seem fairly consistently to be more in the order of 8ft (2.44m) and 4ft (1.22m).

Of course, the key issue is not what these widths were, or are, but what they might be. To that end, the verges either side of the cycleways, together with that often also present between the footway and property line, provide scope for appreciable widening, if necessary. The western end of the original scheme seems to have been just east of the junction of Arnold Road with the A611 Hucknall Road, more or less at the junction with the western end of Gainsford Crescent (which also forms a junction with Arnold Road some 600m further to the east).

The eastern end of the scheme was just west of the junction with Edwards Lane. The latter was a T-junction in the 1930s, but a northern extension to Edwards Lane has since been built, creating a crossroads. Apart from two short shopping parades, the fronting development is almost entirely residential.

Much of the latter post-dates the 1930s, and indeed 1950s mapping shows the north side of the road to have very little built frontage. The large area enclosed by Arnold Road and Gainsford Crescent, for example, though now filled by houses either side of Pavior Road, was then Playing Fields. The dwellings are largely two-storey houses, but some of the more recent stock is in the form of three-storey flats.

Another characteristic of this stretch of Arnold Road is that the dwellings are generally set well back from the carriageway, and often with a separate access road between. This layout may have something to do with the fact that there is a notable fall in ground level from north to south, across the east-west axis of Arnold Road. Also of interest is the fact that the large Nottingham City Hospital campus lies a shortway due south of the section of Arnold Road in question, and is also bounded to west and eastby Hucknall Road and Edwards Lane.

THE CHALLENGES

One of the main challenges faced in making good, contemporary use of the 1930s cycleways on Arnold Road is the fact that the scheme never did engage properly with the junctions at either end. This is characteristic of the 1930s schemes, meaning that the cycleways simply stop short of the Hucknall Road and Edwards Lane junctions – both of which are signalised crossroads today.

Another typical flaw is that the cycleways give up at junctions with side streets, and the challenges related to this are magnified on Arnold Road because the presence of parallel service/access roads has lead to many side junctions being excessively wide. Not all of the junction layouts are 1930s originals.

The roundabout junction with Pavior Road dates from later than the 1950s, and its creation not only made a break in what was originally a continuous cycleway on the north side but also diverted the cycling and walking routes well off the natural desire line, which was originally catered for.

The general condition of the Arnold Road cycleways is also a cause for concern, with many sections being in a poor state of repair, there being numerous obstacles (like railings and statutory undertakers’ boxes), and encroachment of the grass verges having reduced the effective width of some footway and cycleway sections well below what provides an adequate level of service.

Another challenge, though straightforward enough to address, is the layout at bus stops, with some shelters unnecessarily obstructing the passage of people on cycles.

THE OPPORTUNITY

Notwithstanding these challenges, the fact is that, between Hucknall Road and Edwards Lane, the legacy of the 1930s scheme is that there is more than adequate space to create excellent provision for walking and cycling on both sides of the road, without needing to take any appreciable space currently used for moving or parked vehicles.

The fact the road has a large number of homes close by on both sides, that it contains local shops, and that it runs close to the City Hospital means that there is a wide variety of local journeys that could make use of these facilities.

A comprehensive improvement programme to return the footways to their original width, modestly widen the cycleways by repurposing part of the verge, modify the bus stop layouts, and generally resurface and de-clutter would make huge difference in itself and is not constrained by the availability of space.

As for the junctions at each end, there is space to remodel the Edwards Lane signals to provide good priority and safety for walking and cycling; while the City Council already has proposals for improvements at the Hucknall Road end.

These proposals are for the designated north-south cycle route to avoid the constrained junction with Arnold Road by following the quiet Andover Road to the north, crossing Arnold Road at the existing Toucan by the Andover Road/Gainsford Crescent junction, and using the existing off-road cycle path to the south, which will be widened.

Concerning the side-street junctions, there is clearly space for even the widest to be improved so as to provide excellent walking and cycling priority.

While the 2018 Nottingham City Cycling Design Guide shows a template for suchimprovements that has much to recommend it, any future side street layouts should be in accordance with Figure 10.13 of LTN 1/20.

Raynesway, Derby

Location: A5111 Raynesway, Derby

Original Length: 2.45km

Authorities: Derby City Council and National Highways

Derby’s Raynesway — initially known as “Town Planning Road No. 4” — was opened by Alderman Edward Paulson, Mayor of Derby, on September 28th, 1938. It was named for Alderman W. R. Raynes, a long-time chairman of the Derby Estates and Development Committee. An official of the Derby Borough Surveyor’s Department told the Derby Daily Telegraph that the “cycle tracks each side of the road will extend the full length of the new section, a distance of 2,300 yards. They will be nine feet wide, and will have the same surface as the main road, which will be of concrete. Use of them will not be compulsory, but it is expected that they will be of value to cyclists travelling to the Spondon works of British Celanese, Ltd.”

Before building the road, Derby Town Council sent Mr. W. G. Penny, chief engineering assistant of the Highways Department, on a fact-finding trip to the Netherlands to “inspect cycle tracks constructed along main roads in that country.”

The Telegraph reported that the idea was that “much useful information may be obtained in this way.”

“Road authorities on the Continent,” pointed out a Council official, “are much more advanced in catering for cyclists than those in this country.”

The overall width of what became known as Raynesway was 120 ft, “comprising two carriageways each 22ft in width, two verges, each 7ft in width; two cycle tracks, each 9ft in width; two side verges, each 3ft in width; and two footways, each 8ft in width,” reported the Telegraph.

“The carriageways were constructed in concrete, and each was divided into two lanes which were easily distinguished by reason of a difference in the colour of the surface.

“Cycle tracks were constructed in red concrete, and, therefore easily distinguished.”

Much has changed since 1938, however, and indeed the subsequent physical alterations to the Raynesway are much more drastic than any affecting the other 1930s schemes in this report.

Raynesway runs broadly north-south and originally ran, more or less uninterrupted, from a roundabout with the Derby Road/Nottingham Road (what was then the A52) in the north, over what is now the Midland Mainline and also over the River Derwent, to a junction with Alvaston Street in the south.

The late 1970s, however, saw the construction of the Borrowash Bypass as the new alignment of the A52, which passes under Raynesway closely adjacent to the Midland Mainline. To connect Raynesway with the new A52, a new grade-separated junction (of a ‘modified trumpet’ layout) was created – named the Spondon Interchange. The interchange essentially destroyed a roughly 500m section of the original Raynesway, starting around 200m south of the Nottingham Road/ Derby Road roundabout. For that stretch, the 1930s cycleways and footways on both sides were replaced by a single shared-use path on the west side; and this also has an uncontrolled crossing of the Raynesway northbound to A52 westbound slip road.

South of the Spondon Interchange, the original 1930s facilities are still largely intact. However, those on the east side have no connection to or from the north.

On the west side, heading south, the original cycleway and footway continue in more or less their original form for around another 1km before reaching the bridge over the River Derwent. The North pier of this bridge sank about a metre into the riverbed in 1947, causing significant damage. While this was later repaired, and a major refurbishment was undertaken in 2009, the current layout of the footways and cycleways seems on likely to be exactly as originally.

On each side, the combined width of footway and cycleway is around just 4m.

On the west side, the two elements are separated by a simple kerb step, while on the east, the arrangement is a single shared-use path.

South of the bridge, on the west side, little further trace of the 1930s cycleway and footway can be found. Following a junction with the ramp to/from National Cycle Route NCN6, which runs alongside the Derwent, there is a short stretch of shared use path before the route becomes part of Quinton Road – a comparatively new access road for adjacent industrial development.

Cycling must take place in the carriageway and there is a footway on the west side.

At the point where Quinton Road becomes Bellmore Way, it swings away to the west of Raynesway, though an off-road ‘segregated shared-use’ path has been created that keeps close to the A5111. Bellmore Way then swings back east again, to form the west arm of a large roundabout junction with Raynesway. This roundabout is part of the wider grade-separated Raynesway Park junction, between the A5111 and A6, constructed between 2009 and 2011.

Having crossed that wide west arm of the roundabout by way of an uncontrolled two-stage crossing via splitter island, the cycleway continues in the form of a ‘segregated shared-use’ path to a two-stage signalised crossing of the south arm (Raynesway), beyond which a ‘segregated shared-use’ path continues to the historic scheme end at Alvaston Street.

Arising from the A5111 Raynesway’s comparatively recent role as a strategic connection between the A6 and A52, the central part of the 1930s cycleway route is now the responsibility of National Highways, while the northern and southern sections are the responsibility of Derby City Council.

THE CHALLENGES

Following from the necessarily involved scheme description about, it can be seen that the principle challenges in connection with the contemporary role of the Raynesway cycleway arise less from the classic flaws of the 1930s layouts, or indeed from generally poor maintenance, but rather from the character of the changes imposed by the Spondon Interchange and Raynesway Park junction developments, as well as from modifications to the River Derwent bridge.

For the most part, these challenges relate to the fact that, in some sections, the historic separated footways and cycleways have been replaced by comparatively narrow shared-use paths. While these are not insuperable, there is one particular consequence of the major restructuring that will require a particular focus if the cycleway is once again to become a route suitable and safe for all. This is the informal, uncontrolled crossing of the A5111 northbound to A52 westbound slip road.

Despite red surfacing on the slip road carriageway, a diagram 950 sign with ‘Cyclists Crossing’ plate, a yellow-backed advance warning sign comprising both a diagram 950 and a diagram 512 left bend sign, and an additional advance warning diagram 512 sign with a white-on-red ‘Reduce Speed Now’ plate below, there is nothing effective to give any priority to people walking or cycling across. Consequently, people hoping to cross are required to wait and look for a gap that they judge to be sufficient. This arrangement, though understandable in the context of a 1970s approach to the design of strategic highways, is inadequate as a means of enabling ‘8 to 80’ walking and cycling.

Land constraints meant that some of the Spondon Interchange’s slip roads have smaller entry or exit radii than would have been considered desirable at the time. This is the case in relation to the A5111 northbound to A52 westbound on-slip, and there is therefore an advisory maximum speed limit of 20mph, in the context of a wider mandatory speed limit of 50mph.

At the large roundabout that forms part of the Raynesway Park junction, the crossing of the west (Bellmore Way) arm leaves much to be desired. The fact that it is uncontrolled and negotiated in two parts is not unacceptable in principle. However, it is undesirable and unnecessary that the approach from and exit to Bellmore Way, either side of the splitter island, are both two lanes wide, and that the geometry is such as to enable turning at inappropriate speeds, despite the speed limit being 30mph.

In the context of reinstating a high quality, connected walking and cycling route along Raynesway, the fact that the former east-side link was eliminated by the Spondon Interchange, means that the focus improvement must necessarily be on the west side.

However, the 1930s facilities still remain – in generally good condition – alongside the East Service Road, and there are numerous employment opportunities adjacent.

The obvious challenge to enabling the use of the east-side footway and cycleway is the lack of a crossing over Raynesway between the Spondon Interchange and the Derwent Bridge. There is a signalised crossing on the north side of Spondon Interchange, and although this is not part of the National Highways network Raynesway in the north is subject to the same 50mph speed limit as it is on the south side.

Other challenges along the west-side route are more familiar. For example, the three junctions with the West Service Road, between the Spondon Interchange and the Derwent bridge, are all excessively wide, and give no priority to walking or cycling across. Indeed, there are some ‘Cyclists Dismount’ signs. The fact that the main carriageway speed limit is 50 mph adds to the challenge of finding the best design solution.

THE OPPORTUNITY

Put simply, the opportunity is to build on the 1930s legacy to create a high quality cycling and walking route between communities to the north and south, overcoming several major severance features (including the A52, Midland Mainline and River Derwent) and enabling access to a range of employment opportunities.

At 2.5km, the distance between Derby Road and Alvaston Street could be cycled in just 10 minutes at a modest pace, yet for many it will currently seem as though motorised transport is the only option.

For the reasons stated above, the focus of improvement works should, in the first place, be on the west side. Where the original footways and cycleways remain – as they do for long sections – these can readily be improved through resurfacing and modest widening. A 3m-wide bi-directional cycleway, alongside a 2m footway, with grass verges either side of the cycleway, would represent very good provision.

As for the comparatively narrow shared-use path sections, the low footfall, the fact that the width is generally between 3m and 4m, and the likely future cycle flows in such a context, mean that if the full width of the paths is maintained (i.e. all encroachment is cut back), if they are well surfaced and lit, and if they are appropriately protected when immediately adjacent to the main carriageway then they can provide a good level of service for all users.

At the north end of the scheme, there is enough space to create a much better transition between the walking and cycling facilities on both sides of Raynesway and the Derby Road/Nottingham Road roundabout.

There is also the opportunity to create a better connection with the shared-use path on the south side of Derby Road, leading to the key local destination of the Asda superstore.

On the northern section of Raynesway itself, the separate footway and cycleway on the east side can be reinstated, where they have been lost, through the removal of the bus lay-by and the reintroduction of the separating verge. Consideration can also be given to improving the quality of the cycling and walking link along Aspen Drive, just south of the Toucan crossing, which also leads towards the superstore.

As has been mentioned, the biggest single challenge facing the creation of an attractive, cohesive route is the improvement of the crossing of the A5111 northbound to A52 westbound slip road. However, the fact that there is an advisory 20mph speed limit on the slip road points to the potential benefits of measures likely to reduce the speed of vehicles making that turn, and the introduction of a signalised crossing could be part of a package. The best location for such a crossing might be somewhat further south of where the existing informal facility is; and it will also be appropriate to explore the modification of the highway layout leading up to the crossing point, from as far back as the northernmost of the West Service Road junctions with Raynesway.

Any modifications should also seek to increase the width of the ‘segregated shared-use’ path south of the crossing, and increase the degree of separation from the vehicular carriageway.

Each of the West Service Road junctions can be improved, and there is space within the short linking roads to enable the walking and cycling crossings to be set back so that vehicles leaving Raynesway can wait clear of the main carriageway to let people on foot or cycles cross.

At the very least, even if a high degree of priority for people walking or cycling across cannot be achieved – because of the speeds of vehicles leaving a main carriageway with a 50mph limit, there is scope to reduce turn radii, and hence vehicle speeds, appreciably.

A detailed review of the collision record and any other previous issues recorded concerning the layout of the A5111 and junctions in this area should inform any proposals for change. (Crashmap indicates that, on the west side of Raynesway between the south side of the Spondon Interchange and the southern junction with the West Service Road, there were seven collisions in the five years 2017 to 2021 resulting in 13 injuries, four of which were serious.)

Further south, opportunities include improving the transition between cycling in the Bellmore Way carriageway (in both directions) and the off-road ‘segregated shared-use’ path that takes a more direct line to the Bellmore Way/ Raynesway roundabout. At the roundabout itself, all arms of which are subject to a 30mph limit, there is – at the very least – a clear opportunity to substantially modify the west (Bellmore Way) arm, and the quality of the walking and cycling crossing over it.

While a comprehensive remodelling of the roundabout could perhaps be considered, the Bellmore Way arms stands out as being ‘over-designed’.

The entry and exit could both be a single lane, and the turn radii could be significantly reduced. Under such circumstances, an uncontrolled crossing would be acceptable, and the splitter island could be modified to provide both a wider and a deeper crossing/waiting area.

Narrowing the Bellmore Way entry to a single lane would also enable widening of the ‘segregated shared-use’ path on the south side and appreciably reduce the angle between that path and the direction of crossing (which is unnecessarily close to a right angle as things stand).

Modifying the entry radius could also provide a more generous waiting area on the north side of the signalised two-stage crossing over Raynesway towards Alvaston Street (at the north east corner of the Lidl car park).

In addition to better connecting the Raynesway cycleway and the path on the south side of Derby Road, there’s a need to improve the Derby Road path itself, to create a much better route to/from Asda.

As things stands, the shared use facility between Raynesway and Aspen Drive is little or no wider than 2m and has obstacles in it.

There is no walking or cycling priority over the excessively wide mouth of the Aspen Drive junction; while east of this there is almost 6m of public highway space on the south side of Derby Road, but the majority is given over to a grass verge. This should be narrowed to create a 4m shared use path.

At the south end of the 1930s scheme there’s the opportunity to create a high quality walking and cycling connection with the Alvaston local centre, a few hundred metres along the A5111. The space is there.

Between the Raynesway Park and A6/London Road roundabouts, it’s in the form of wide service roads on both sidea.

On Shardlow Road, there’s at least 3m in the form of a third northbound lane between Blue Peter Island and London Road that could be repurposed.

Melton Road, Thurmaston, Leicester + Leicestershire

Location: A607 Melton Road, Thurmaston, Leicester

Original Length: 1.4km

Authorities: Leicester City Council and Leicestershire County Council

What is now the A607 Melton Road has a long history. Its general straightness is a clue to the fact it is built on the same alignment as the Roman Fosse Way and, in the 18th Century, it was improved as part of the Melton Mowbray turnpike.

An announcement that cycle tracks would be constructed as part of the scheme to create a dual carriageway on part of Melton Road was made in 1936.

“Another scheme that is to be carried out is the widening of Melton-road from the tram terminus to the city boundary,” reported the Nottingham Journal in that year, adding that the road “will include a special track for cyclists – the first in the Midlands.

Subsequently, in 1937, the Leicester Evening Mail reported that “The Surveyor’s Department of Leicestershire County Council is about to begin a survey of the land and the preparation of plans for the scheme.”

The newspaper added that “It was considered by the parish council that the construction of the road was an urgent matter.”

Based on this information, it is probable that the cycle tracks were installed some time between 1937 and 1939.

Evidence on the ground and from historic mapping suggests strongly that the cycleways originally extended from the junction with Lanesborough Road in the south to just south of the junction with Manor Road in the north. Lanesborough Road wasn’t built until at least 20 years later, and the junction in question was originally with Wavertree Drive.

The northern end of the scheme is at the boundary between Leicester City and Leicestershire County. The cycleways were constructed on both sides of the road. However, it would appear from what’s on the ground today that, for large sections on the west side (and much shorter sections on the east), the form of provision for cycling was not a distinct cycle track but rather a lightly-trafficked service road.

Although this is typical of many 1930s-era cycleways, it is unclear whether these service roads were an original feature or a later modification.

The major physical interventions since the construction of the 1930s cycleways have been the creation of a major signalised junction with the A563 Leicester Ring Road (Watermead Way and Troon Way at this point). A second new signalised junction on the Melton Road has also been introduced, a short way north of the A563, to provide access to the Sainsbury’s superstore on the east side.

As a consequence of both these interventions, the original east-side cycleways at and between the junctions have been destroyed.

As stated, there are several sections of service road on the west side. The fact that vehicles are permitted on these sections, allied to the industrial character of much of the adjacent land use, means that the cycleway is much less well-observed than its counterpart on the east side.

Levels of cycling are likely also suppressed by the fact that there is no signalised crossing over the west arm of the A563.

South of the southern end of the 1930s scheme, Melton Road is laid out as a single carriageway that varies in width from around 10-12m. The street has a mixture of residential and local commercial frontage, with much of the kerbside space used for parking.

Melton Road is an important bus corridor, and a southbound buslane runs from the A563 to around 200m south of the end of the 1930s scheme.

Rushey Fields Recreation Ground is just south of the scheme on the east side of Melton Road, and a shared usepath runs through it.

As is the case with many 1930s cycleways, the northern end is particularly abrupt. The quality of cycling links between it and Humberstone Lane/ Thurmaston local centre (east side) and the old single carriageway section of the Melton Road (west side) is generally poor.

National Cycle Route NCN6 runs parallel to Melton Road, a few hundred metres to the west. A direct, shared use path link between the twolink was recently constructed, joining Melton Road at almost exactly the northernmost extent of the 1930s scheme.

THE CHALLENGES

The 1930s cycleways on Melton Road suffer from three principal problems that are generic for all the cycleways built in that era: they give up at junctions – even those with minor side streets; they do not themselves connect important origins/destinations; and they terminate abruptly without connecting to a wider cycling network of similar standard.

Another important issue in relation to the Melton Road cycleways is the physical condition of the surface. This seems largely to be the original concrete, which has endured remarkably well.

However, along with general wear and tear of the comparatively rough original surface, there are numerous ruts, cracks and patches related to localised failures, at joins between sections of concrete and as a result of tree root damage.

There is also the matter that the cycleway on the west side is considerably less attractive for cycling than that on the east. While the east-side cycleway is largely continuous – whether in its original or a modified form – the cycling provision on the west side is much less so.

There are numerous sections that are service roads, where parked vehicles often obstruct passage. The section alongside the industrial area north of Lanesborough Road has been damaged by previous interventions. What was the footway there is now largely used for parking (and a food wagon!) so that even where the 1930s cycleway is in good condition it is largely used as a footway. And there is no crossing over the west arm of the A563 Ring Road junction.

Casual parking in the cycleway is another challenge – and again one that’s common to a number of other 1930s cycleways.

On the east side, the historic cycleway has been lost between just north of the Sainsbury’s junction and the southern edge of the open space on the south side of the Ring Road junction, a distance of almost 300m. What’s now in its place is a shared-use path of varying dimensions, the widest section of which (between the Sainsbury’s and A563 junctions) is compromised by the fact of localised narrowings to accommodate the poles that support three separate, large directional signs on approach to the Ring Road.

There is then also the matter of the cycling facilities at those signalised junctions themselves. The Sainsbury’s junction provides a two-stage crossing that is shared with people on foot, while the A563 crossing is in three stages each of which is also shared with people on foot. These arrangements accord walking and cycling a very low priority, and although this is perhaps understandable in the context of the A563 junction, it is less so at the Sainsbury’s junction.

In addition to the general inconvenience and delays created by the multi-stage arrangements, the dimensions of the layouts make movement on foot or cycle far less comfortable than needs to be the case.

Even if the basic signalling arrangements are unchanged, appreciable improvements could be made by enlarging islands and widening crossing points.

South of the A563, the east-side cycleway and footway are largely intact, if in poor repair, and the major issue is that of the layout of side street junctions.