“LEPER WAYS”: WHY DID CYCLING ORGANISATIONS HATE CYCLE TRACKS?

In the 1930s, the provision of Dutch-inspired cycle tracks in Britain was perceived by cycling organisations as a means of reducing the utility of cycling in order to cut the number of cyclists who dominated Britain’s roads. It was also seen as an attack on the right to ride on the road, granted fifty years earlier.

As discussed elsewhere in this study, many motorists — the majority of whom were upper- and middle-class — fervently desired the building of cycle tracks, assuming that such provision would enable faster, smoother driving. Motoring organisations also lobbied for cycle tracks, framing their provision as a safety concern, stating that cyclists should be compelled to use tracks to “save lives” but also often adding that cyclists were slow and had less right to use “modern” roads.

Cycling organisations — leading officials of which were middle-class car owners — believed that the separation from faster, heavier vehicles offered by cycle tracks provided only fleeting safety because the first ones offered no protection at junctions and, instead, reintroduced cyclists into the “maelstrom” of motor traffic where motorists would have been least expecting them. Cycling officials also feared that motorists would drive faster and more dangerously without cyclists acting, in effect, as rolling speed bumps.

Instead of campaigning for wider, smoother cycle tracks with protection at junctions — examples of which were starting to be built in the Netherlands — organised cycling boycotted the new infrastructure and demanded other measures instead. These included slower driving speeds, tougher sentencing for those convicted of dangerous motoring, and wider roads in which motorists and cyclists could share in presumed greater harmony. Perhaps unexpectedly, cycling organisations also advocated for “motor roads” from which cyclists would be excluded and which, it was believed — wrongly, of course — would free up all other roads for the almost exclusive use of pedestrians and cyclists.

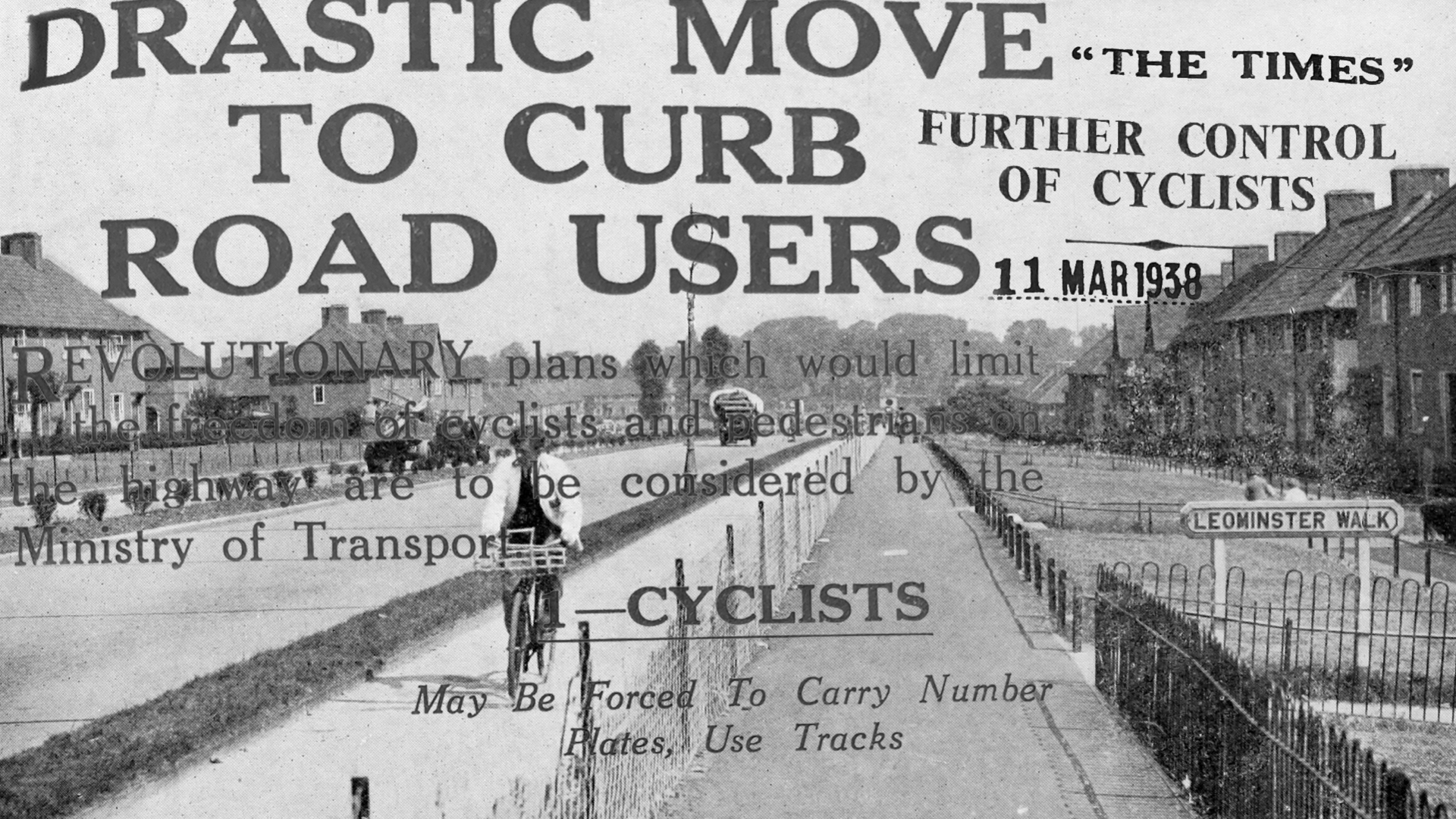

Planners and road engineers — bristling with excitement at creating infrastructure for what almost everybody considered the transport mode of the future — designed roads that excluded or separated slower-moving vehicles, including cyclists, who dominated even on trunk roads. In the early to mid-1930s, Britain experienced a cycling boom, with working-class cyclists doubling in number in just a few years, much to the surprise of Ministry of Transport officials and the annoyance of motoring interests. There were two million motorists in 1936 but over twelve million cyclists.

Despite motorists being the newest and least numerous actors on the scene, most local authorities wished to build for motorists alone. This motor myopia was tempered by central government — from 1936 onwards, local authorities were only provided with generous road-building grants if they included cycle tracks in their plans. While this provision would be seen as equitable by most modern cyclists, it was seen at the time by organised cycling as a means to control and reduce the number of cyclists.

Ministers and their mandarins, by dint of their social class and inclinations, were heavily biased in favour of motoring, but they felt duty-bound to appear neutral. None of the six transport ministers between 1934 and 1944 stated publicly that cycle tracks were designed as a utility for faster motoring. Instead, they and their officials framed the putative network as something that would reduce the extremely high number of cyclist deaths.

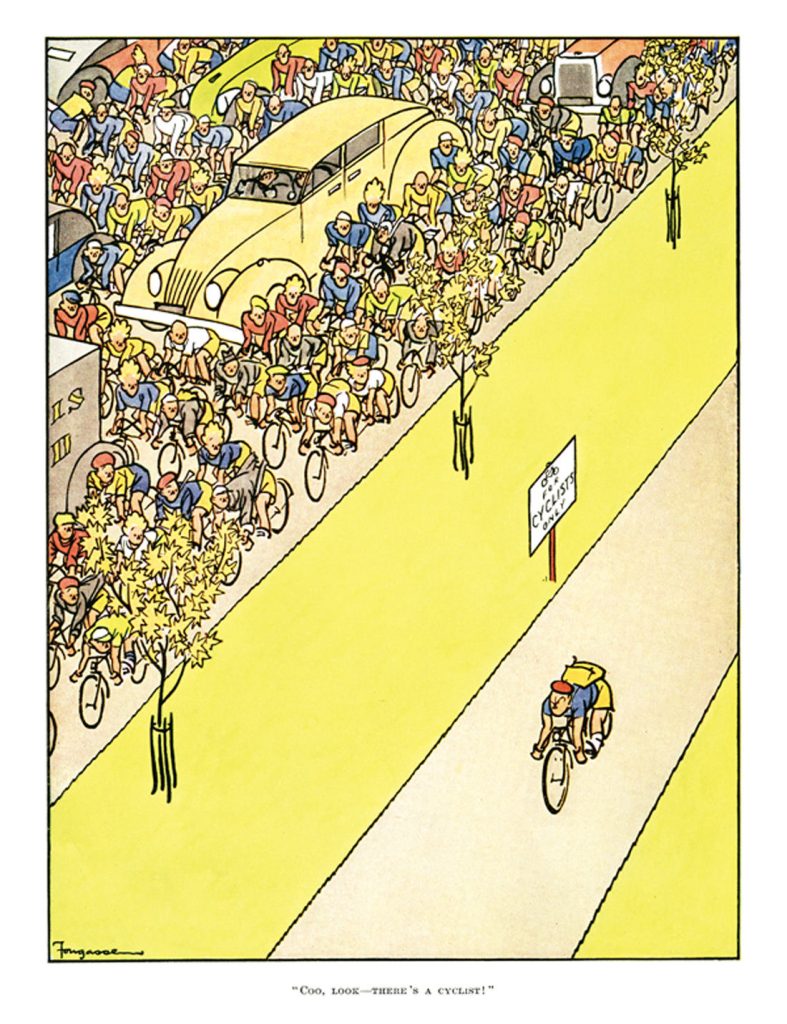

1938 Punch cartoon by Fougasse ridiculing organised cycling’s opposition to the 1930s cycle tracks. Fougasse was the name used by Cyril Kenneth Bird, an English cartoonist who would later become famous for his “Careless talk costs lives” WWII propaganda posters.

Today, kerb-protected cycleways are seen as a mainly Dutch and relatively modern intervention and worthy of widespread adoption as both a safety measure and a way to encourage people to cycle. The fact that Britain once started to build a network of protected cycleways is now largely unknown, mainly because they fell out of use in the 1940s and 1950s. This was not due to organised cycling’s opposition to the new-build cycle tracks — the Ministry of Transport majority-paid for 100 or so schemes around the country, ignoring the desires of officials from the Cyclists’ Touring Club and others. Some leisure cyclists claimed that cycle tracks would deter “pleasure riding,” but it’s clear from period traffic counts that most utility cyclists preferred riding on the cycle tracks. Today, those cycle tracks designed well in the 1930s are still used by cyclists — for instance, the six miles of cycle track beside the Rainford bypass in Lancashire may have several side roads with seeming priority for motorists, but many “roadies” seem to prefer the off-carriageway route to mixing it with fast-moving motor traffic.

Cyclists eventually banished themselves from the roads by giving up cycling. Cycling levels fell off a proverbial cliff after 1949. The existence of cycle tracks around the UK did nothing to arrest cycling’s eventual decline, and — given cycling’s low status from the 1940s onwards — it’s reasonably unlikely that a longer, improved, and joined-up network would have fared any better. Cycle use remained high in the Netherlands for many reasons, including cultural ones, not just because of the country’s long-existing cycle networks.

Below I expand upon organised cycling’s fear that the building of cycle tracks was the start of an official campaign to banish cyclists from the roads and ask whether officials from cycling clubs and representatives from cycling organisations were right to be fearful.

RIGHT TO RIDE

British cycling organisations and prominent cycle journalists opposed the provision of cycle tracks in the UK even before they were built, fearing that cyclists would be forced to use such infrastructure and soon thereafter forbidden from using the “public highway.”

The so-called “right to ride” was a highly charged issue for cyclists in the 1930s. The right to ride cycles on British roads had only been officially granted in 1888 with the passing of the Local Government Act. Section 85 of this Act — which created County Councils — declared that “bicycles, velocipedes, and other similar machines are hereby declared to be carriages within the meaning of the Highway Acts.”

Defined in law as carriages, cycles from 1888 onwards could no longer be prevented from riding on the public highway by local bylaws and the like. This was a significant and much-celebrated concession, and it had been hard fought for by organised cycling, especially by the Cyclists’ Touring Club. In the year of its passing, a writer in the Law Journal billed the Local Government Act as the “Magna Carta de Bicyclis.”

For cycle organisation officials of the 1930s — some of whom had personal recollections of the passing of the 1888 Act — the right to cycle on the roads of Britain was not something to be surrendered or watered down.

In the 1880s, there were no motor cars on British roads, but by the 1920s, the growth of motoring had led to increased danger on the roads for cyclists (and pedestrians), and there were calls from motorists for cyclists to be provided with separated infrastructure, the equivalent to pedestrian-only footways. In the 1920s, cycle tracks were championed by, among others, the Roads Improvement Association, an organisation founded by officials from the Cyclists’ Touring Club and National Cyclists’ Union in 1886 but was wholly a motoring organisation by 1903.

Throughout the 1920s, motoring columnists in national and local newspapers argued for the “segregation” of cyclists and lobbied for the provision of cycle tracks.

In 1929, a cycling journalist writing in the Daily Herald (a tabloid national newspaper that later morphed into The Sun) reported that a “special cycle path” was to be built along a short stretch of London’s Great West Road. “It is all made to sound most fascinating — a special track for cyclists — no danger of being run down at night or hustled off the road in the day by scorching motorists …”

But, the writer felt there was, in fact, an ulterior motive for the provision of such tracks:

“It would be all very well if with the special track there remained the right to ride on the road, but it is certain that the latter would go with the opening of the former. Once this process starts it will continue under pressure of the motoring bodies until cycles are forbidden to ride on the public roads.”

The fear there would be a compulsion to ride on the “special cycle tracks” and, thereafter, there would be a general extinguishment of rights to ride on ordinary roads coloured the views of many cycling officials in the 1930s and for at least the following thirty years.

CYCLISTS AS MAJORITY ROAD USERS

In the mid-1930s, Britain’s twelve million cyclists dominated many British roads, including the new “arterial” ones. On approaches to large factories and dockyards, cyclists at clocking-off time clogged the roads solid. “It is indisputable that the number of cycles on the road is far in excess of the total of all other classes of road vehicle, public and private, passenger and goods,” admitted the Minister of Transport.

A 1935 census conducted by the Ministry of Transport reported that cyclists accounted for 80 percent of Bedford’s vehicular traffic.

For many motorists, this dominance by “hordes” of cyclists was intensely irritating, and the desire to force cyclists to keep to the road’s margins was expressed both by direct action — close passes of cyclists are nothing new — and by lobbying for cyclists to be corralled, thereby controlled and, hopefully, their numbers reduced.

Writing under the pen-name Kuklos for his weekly cycling column in the Daily Herald tabloid, William Fitzwater Wray complained in 1936 that the government planned to “spend 120 million pounds in giving the nation more room: but the largest section of road-users shall have much less room than before … the traffic which has increased 95 percent in five years must have paths 6ft. to 9ft. wide.”

Motoring interests framed the segregation of cyclists as a measure to reduce what was a dreadful death toll among cyclists. Cycling organisations believed that the true motive for cycle-track provision was to force cyclists to use narrow, inferior paths to increase the utility of motoring. A 1937 pamphlet produced by the Cyclists’ Touring Club voiced this concern:

… most people and organisations who advocate cycle paths are not actuated by motives of benevolence or sympathy… If they did, as they suggest, recommend them merely because so many cyclists were being killed they would naturally recommend separate paths for motor cyclists as well, for the death rate among motor cyclists is the highest of all road users and fifteen times as great as that among cyclists. A great deal of the cycle-path propaganda is based on a desire to remove cyclists from the roads. That is why the request for cycle paths is so often accompanied by a suggestion that their use should be enforced by law. Therein lies a serious threat to cycling.

The CTC also believed in the out-of-sight, out-of-mind theory that once cyclists were removed from some roads, motorists would not want to see them on any roads:

The provision of some roads with cycle paths would naturally confirm inconsiderate motorists in a false belief that they need have less regard for other classes of road users. Driving would become faster and more reckless on all roads, including the majority of roads that could not be provided with cycle paths.

MOTORDOM DEMANDS SEGREGATION

Two years before the building of the high-quality cycle tracks beside Coventry’s Fletchamstead Highway — part of the A45 — the managing director of a car company with an off-highway factory wrote that “freedom will have to be restricted and a sense of responsibility shouldered.” The Standard Motoring Company’s John Paul Black was talking in 1935 about cyclists. “Cycle tracks have been introduced, but no effort is made to enforce their use,” he complained in the Times.

Freedom was for motorists alone, thought many prewar motorists and the organisations representing them. Giving evidence in 1938 to the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents, Gresham Cooke, secretary of the British Road Federation, said: “I should like to see it made an offence [for cyclists not using a … cycle track] where it exists. There is a great deal of criticism of cycle tracks and the state in which they are, but where they exist, we certainly urge that it should be an offence not to use them.”

Admiral G. H. Borrett of the Company of Veteran Motorists also gave evidence to the committee. “Cycle tracks, of course, are most desirable,” he told the peers. “They should be wide enough, and when there are sufficient of them we think they should be made compulsory.”

Citing evidence given to the select committee The Times reported: “Further restriction on pedal cyclists were among the suggestions submitted by the Royal Automobile Club … [which] was of the opinion that certain legal obligations of a character which it would be no hardship on the cyclist to observe should be made [including] the provision of cycle tracks.”

Later in the year, and referring to a separate fact-finding mission, The Times editorialised: “[New] main roads should be equipped with tracks on both sides, and … the use of these tracks should be made compulsory … subject to commonsense relaxation of any such compulsion at certain times and in certain places.”

ORGANISED CYCLING OPPOSED TRACKS

“The demand for separate tracks for cyclists is part of the campaign of motorists to appropriate public highways for their exclusive use,” claimed George Herbert Stancer in 1934. The long-time secretary of the Cyclists’ Touring Club continued: “Have we yet got to accept a condition of affairs when cyclists have to renounce their use of the roads to escape annihilation?”

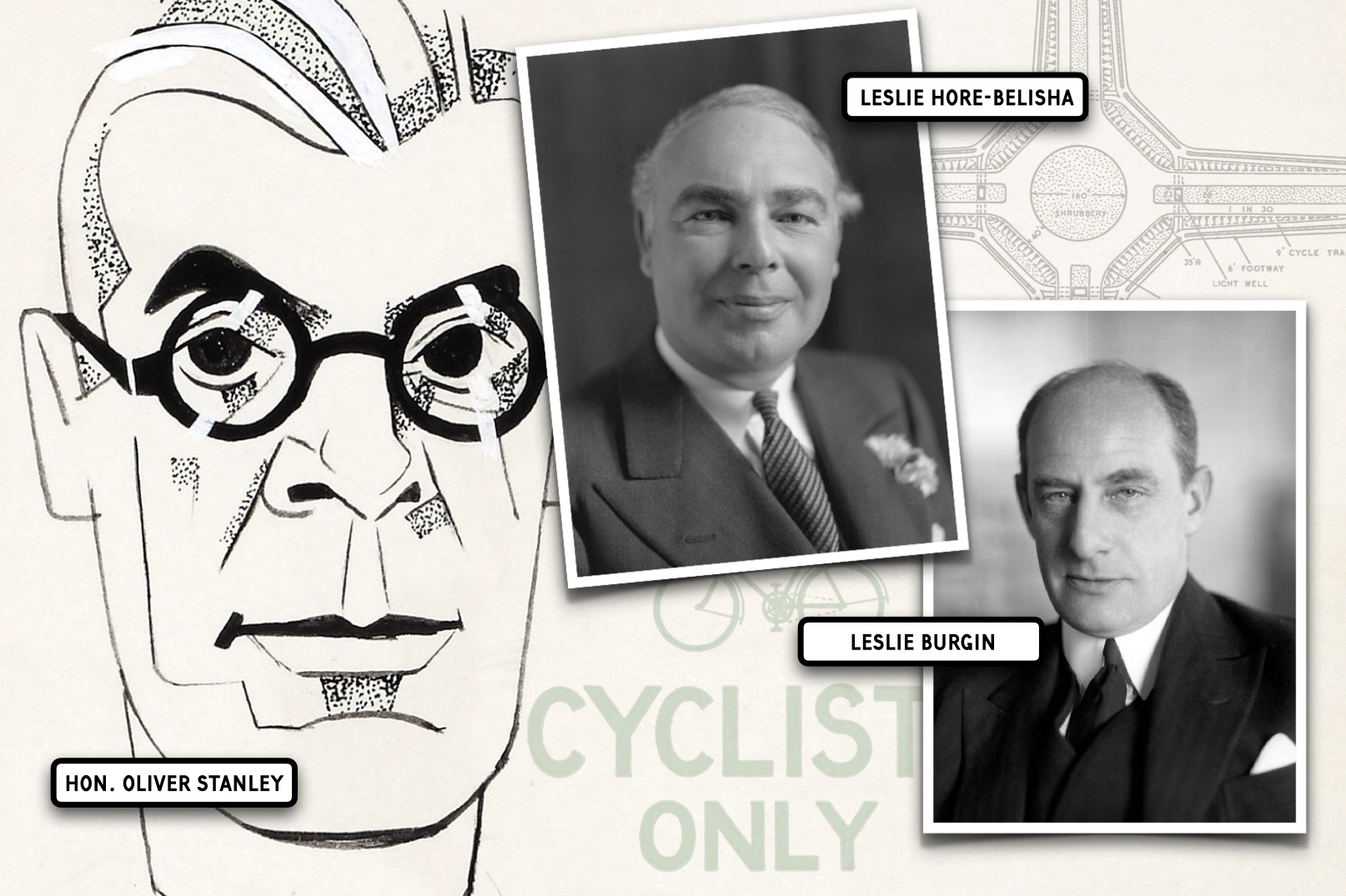

Kuklos complained: “The baser elements of the automobile world — the mile-a-minute roughs and the motoring journals — are panic smitten at the steady growth of cycling. They seem to have the ear and the sympathy of the Ministry of Transport. [Transport minister] Oliver Stanley … proposes to try ‘special tracks for cyclists.’

“But however much of the public moneys Mr Stanley wastes on tracks for cyclists, let cyclists understand clearly that there is no law to compel the use of them.”

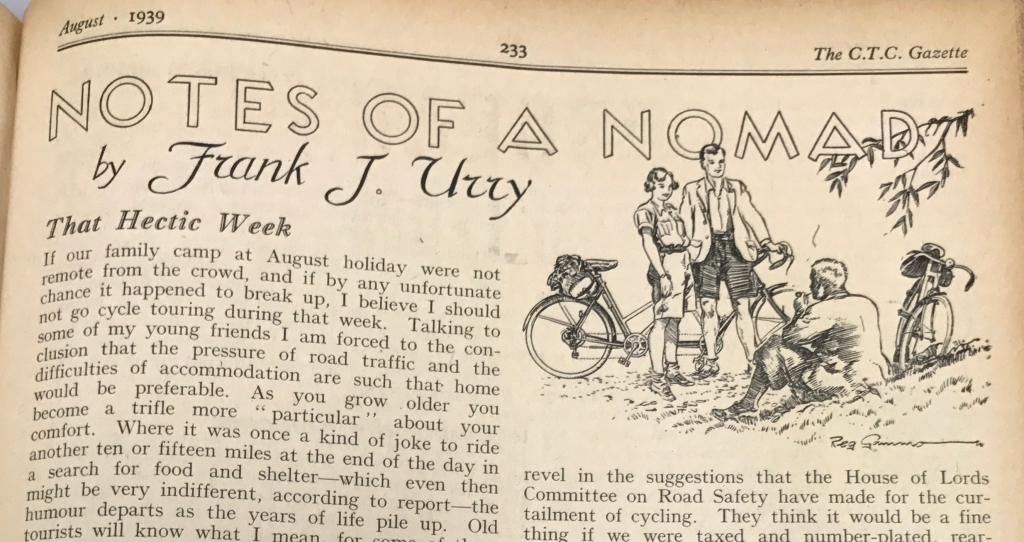

Calling the proposed tracks “Leper Ways,” Kuklos predicted that the government planned to “exclude cyclists from the road wherever such tracks are provided.”

(Other terms for cycle tracks used by Kuklos included “little paths” and the profoundly unsavoury “concentration camps for cyclists.”)

The veteran cycle tourist added:

“I have cycled on [cycle tracks] in France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Holland and Denmark. They were made by benevolent Governments for the largest section of road-users because the roads were not good enough. That’s why I used them!”

He intimated that British roads were far better than those abroad and, therefore, did not need the addition of separated tracks.

The following year, some six months after the creation of the first track, members of the Cyclists’ Touring Club meeting at a London hotel unanimously passed a resolution protesting such infrastructure:

… this general meeting of the Cyclists’ Touring Club deprecates the view of the Minister of Transport, as indicated by his approval of cycle paths, that the segregation of cyclists is a just method of minimizing the number of road casualties, and strongly urges upon the Minister its opinion that the problem can be more satisfactorily dealt with by the rigid enforcement of the existing laws, which were instituted with the object of enabling all sections of responsible road users to enjoy the full exercise of their rights in safety … Cyclists were not going to allow themselves to be pushed off the roads and segregated onto a track on the side. The only way to end the shambles of the roads, which had become a national disgrace and crime, was to lay the culprits by the heels and put them in gaol.

There were also letter-writing protests. Oxford cyclist J. Gilbert Wiblin wrote to The Times in 1935:

… we are far from convinced that the degree of safety afforded by segregation would prove to be as great as its advocates allege … In 1933 nearly three times as many pedestrians as cyclists were killed, though the former have long had their separate footpaths; and three-quarters of those pedestrians were killed in built-up areas — just where foot-pavements are most adequately provided. Whatever contribution, therefore, separate paths have made to protect the pedestrian … they clearly have not completely solved the problem of his safety; and there is no reason to suppose that special tracks would contribute in greater measure to the safety of the cyclist …

Ernest Snowden of the Anfield Bicycle Club suggested that the provision of cycle tracks was not a benefit to cyclists but so that motorists could drive faster: “It needs no prophetic ear to detect the knocking of the enemy at our gates … clamouring that we should forfeit our freedom of the roads, that he may … hurl his death-dealing machines across this fair land of ours, utterly regardless of the lives and rights of the great non-motoring majority …”

Snowden urged that individual cyclists and cycling groups should stand together to fight against the tracks. “We are a disintegrated whole, possessing neither abundant strength, nor far-reaching power, yet by unity both may be attained. Already the two great bodies which represent cycling interests are joining forces against the common menace …”

A mass meeting of cyclists was held in the centre of Liverpool in January 1935. Another protest was held in London — 500 club cyclists met in Hyde Park before riding to the cycle tracks on Western Avenue which they pointedly refused to ride along, choosing to cycle in formation on the main carriageway, three and four abreast. “It is no use grousing that the cycling organisations should do this and that: ask yourself what you are doing!” thundered Snowden. “If you are driven off the roads on to cycle paths, you will only have yourself to blame…”

The Cyclists’ Touring Club organised protest rides against cycle tracks elsewhere in the country, too, including one in 1937 that briefly blocked the York to Malton arterial, today’s thundering A64.

“The proposal is to make a demonstration of a refusal to use the [cycle tracks],” John Bevan told the Yorkshire Evening Post. Bevan, who was secretary of the CTC county branch, said the mass ride would “take place on a very busy day” and suggested that club cyclists might station themselves at the entrances to the cycle tracks on weekends handing out literature urging “private cyclists” not to use them. “Following our usual practice when the rights and privileges of cyclists are threatened, we raised objections when the scheme to make these tracks was first mooted,” Bevan pointed out.

Opposition to the first cycle tracks came from the Cyclists’ Touring Club, the National Clarion Cycling Club, the National Cyclists’ Union, bicycle manufacturers such as Hercules, and the bicycle industry’s representative body. H. R. Watling, director of the British Cycle and Motor-cycle Manufacturers and Traders Union, voiced his worries: “I think cyclists in general fear that if cycle tracks are provided in certain places the psychology of the motorist will be affected adversely . . . they will regard the cyclist as more and more an undesirable person on the road, and it may lead in some cases to an increase in the degree of carelessness exhibited by drivers of all types.”

(Hore-Belisha described representatives of cycling groups as “hysterical prima donnas.”)

Sir Edmund Crane, chairman of Hercules, then the biggest-selling utilitarian bike brand, believed that cycle tracks were “fantastically futile” and that “thoughtful and considerate motorists do not desire the segregation of cyclists, even if it were possible.”

Crane added, optimistically, that motorists “recognise that, if at times the cyclist is a nuisance to them, they are often a nuisance to the cyclist.”

Kuklos calculated that even if as many cycle tracks were built as promised, this would still be but a drop in the ocean: “Mr. Hore-Belisha plans to construct ‘nearly 500 miles of cycle-paths in five years.’ That’s 100 miles per year. We have 178,000 miles of highway in this country. That’s 1,780 years to fit Britain with cycle-paths.”

Kuklos added: “Hypocrites urge that paths are necessary ‘for the cyclist’s own safety.’ That is an obvious admission that the State allows the public roads to be dangerous to the majority of users.”

Making the Roads Safe: The Cyclists’ Point of View, a 1937 pamphlet from the CTC, stated:

It is impossible to escape the conclusion that most people and organisations who advocate cycle paths are not actuated by motives of benevolence or sympathy, although they may declare that their sole concern is the welfare of the cyclist … A great deal of the cycle-path propaganda is based on a desire to remove cyclists from the roads. That is why the request for cycle paths is so often accompanied by a suggestion that their use should be enforced by law. Therein lies a serious threat to cycling. It has nothing to [do with] road safety … but is a profoundly important reason why cyclists should oppose cycle paths. Otherwise they may lose their legal right to use the public roads — a right won for them almost fifty years ago by the Cyclists’ Touring Club.

It’s probable that millions of working-class cyclists didn’t share these concerns. Those who cycled for utility alone were far less ideologically inclined, and much more likely to use cycle tracks, although the huge numbers of cyclists at this time meant that cycle tracks couldn’t have hoped to cope at peak times, a point made by CTC’s Stancer in 1943: “Compulsory cycle paths on any large scale would [not] provide for anything more than a mere trickle of factory workers. The moment the stream begins to swell it overflows.”

At the Club’s AGM in 1947, by which time many miles of cycle tracks had been built, Stancer “moved a motion expressing determined opposition to cycle-paths alongside public roads, protesting against the threatened exclusion of cyclists from the carriageways and calling for the restoration to the Highway Code of the precept that “all persons have a right to use the road for the purpose of passage’,” wrote William Oakley in Winged Wheel, a 1977 Club history.

The 1946 Highway Code advised: “If there is a cycle track — use it.” Through continued opposition, CTC secured a victory of sorts in 1954 when “adequate” was added to the wording, softening it to “If there is an adequate cycle track, use it.”

MINISTERS AND MANDARINS

In 1935, Transport Minister Leslie Hore-Belisha admitted that cycle tracks would not be built on every road but denied there was any plan to ban cyclists from the highway. His private secretary told one letter writer:

It should be obvious that it will never be possible to provided separate tracks for cyclists on more than a small percentage of public highways of Great Britain and there is therefore no question of the permanent exclusion of cyclists from the roads as a whole. In view of these facts it is Mr Hore-Belisha’s earnest hope that the cycling organisations will not persist in opposition to these cycle tracks.

Transport ministers in the 1930s said in parliament many times that they did not wish to remove the rights of cyclists to ride on the highways of Britain and that there were no plans — “at present” — to make it compulsory for cyclists to use the new cycle tracks (compulsion that was already common on the continent.)

A search through Hansard reveals what ministers said in public, but reading what they said in private can be more revealing because this is often at variance to public utterances. I have scoured Ministry of Transport archives, looking at the private correspondence between officials in the Ministry of Transport and MPs and members of the public. They reveal ministers and mandarins fearful of the terrible death toll on Britain’s roads in the 1930s — with 845 cyclists killed between 1928 and 1933 — and wanting to reduce this slaughter.

While ministers, planners, and road engineers often wheeled out the “safety” argument — even in private — there were often indications that another motive was to “free” the road of slower-moving vehicles in order for motor cars to drive faster. Then as now, speed — or the lack thereof — was a preoccupation for many motorists. A Ministry of Transport research project of 1936 found that, despite the building of many new roads, motor vehicle speeds in London remained low. The average speed was found to be just 12.5 mph, and there was a constant desire to find ways of increasing such speeds.

According to Clifford Glossop, the Conservative MP for Penistone, cycle tracks were necessary because motorists wanted the roads to themselves — they often bullied cyclists, he said. In 1934, he told parliament the “wretched cyclist is always being frightened by the hoot of an electric horn and is very often forced into the ditch or into the kerbstone. We should consider the placing of special cycling tracks at the side of main roads, as in Continental countries, particularly Holland.”

In reply, the then Minister for Transport Oliver Stanley agreed that there was a “possibility of introducing special cycling tracks … not with the intention of forcing [cyclists] to use it, but with the possibility that if they become familiar with its use their opinion of its utility may be changed”

Later in 1934 Hore-Belisha became the Minister of Transport and he, too, was in favour of cycle tracks. But not compulsion, he claimed.

“The Minister would prefer that cyclists should be persuaded to use these tracks by the convenience and security which they offer rather than by Regulations,” wrote Hore-Belisha’s private secretary to a member of London’s Carlton Club.

Hore-Belisha didn’t understand why cycling organisations remained opposed to the planned cycle tracks. At the opening of the Cycle and Motor Cycle Exhibition at London’s Olympia in 1934, Hore-Belisha complained:

“It is curious that cyclist organisations stand almost alone in opposing or mistrusting the provision of special facilities for their use and safety.”

He also pointed out: “Pedestrians clamour for footways and for field paths, and I am entirely in sympathy with their desire … Why are cyclist organisations so suspicious? When some benevolent local authority provides seats alongside a road, one does not hear insinuations that this is a sinister plot to prevent wayfarers from sitting on the grass.”

P. J. H. Hannon, the MP for Newcastle and one of the CTC’s pet parliamentarians, wrote to Hore-Belisha, worrying that once “cycle paths are introduced, the bicycle rider will be expected to use them, and in due course, will be debarred from the highway.”

In a CTC magazine editorial, it was suggested that this removal from the highway wasn’t about so-called motorways:

As quickly as decency will permit [politicians] will seek to restrict us to the paths wherever these have been laid down so that their ideal of completely mechanised highways can be attained — “roads fenced off like railways and reserved for cars and commercial vehicles,” as a member of our motoring nobility recently prophesied. And he was referring, be it noted, to our existing public roads, and not to the possibility of constructing special motor roads at the expense of motorists.

Otley’s Tory MP, Sir Charles Grenville Gibson, didn’t ever speak in parliament about cyclists and cycle tracks. Still, he did so privately to Hore-Belisha, promising that cyclists would “become accustomed to [cycle tracks] and they will not raise the slightest objection.” He added, much in hope: “I believe in Holland, cyclists are prosecuted if they travel on the main highways.”

In an internal Ministry of Transport document, Hore-Belisha’s private secretary, D. E. O’Neill, admitted that the minister “received a large volume of correspondence” on the matter of cycle tracks, including protests from cycling organisations fearing “Machiavellian” compulsion but that it was preventing cyclist deaths that truly motivated him. “[If] … the Minister had not attempted anything for the protection to cyclists, he might rightly have been criticised.”

He added, “I know that cyclists in general fear that at a later stage they may be forbidden to use the highway where these tracks are provided, but “there is no present intention to make the use of the tracks compulsory.” [My italics.]

O’Neill wrote to another correspondent that there was “no question of the permanent exclusion of cyclists from the roads as a whole,” and that it was Hore-Belisha’s “earnest hope that the cycling organisations will not persist in opposition to these cycle tracks.”

Regular behind-the-scenes correspondents to the minister included G.A. Olley, who, back in the 1890s, had been a record-breaking time-trial rider. Unlike many of his fellow club cyclists he welcomed the introduction of cycle tracks (and, in fact, he had been writing to the Ministry suggesting their building since the late 1920s). But he did worry about compulsion, and wrote to Hore-Belisha seeking his views on the matter.

For a 1935 talk he was to give to his fellow record breakers, Olley wanted an assurance from the minister that the “existence of a reserved cycle path would not prevent a cyclist … making use of the main motor vehicle track if he wished to do so.”

O’Neill replied: “[The minister] asks me to assure you that as at present advised it is not his intention to forbid the use of the main carriageway to cyclists on roads where a separate cycle track is provided. Clearly, however, these tracks would fail of their effect unless cyclists used them wherever they were provided.”

Undeterred, Olley wrote again, asking roughly the same thing and, again, O’Neill said the feared plans were not — presently — on the cards.

“Mr. Hore-Belisha’s motive in introducing separate tracks for cyclists,” wrote O’Neill, “is simply and solely to give cyclists a greater degree of safety on the roads.”

Writing privately to his parliamentary friend Oliver Locker-Lampson (an MP who had a fascinating and influential life yet who is largely unknown today), Hore-Belisha said:

“I have great hopes that when the cyclists realise that these tracks are entirely for their own safety and are not a subtle method of depriving them of their legitimate rights they will change their present attitude.”

In parliament, Hore-Belisha’s successor as transport minister was asked by Sir Alfred Beit whether he would “take steps to make compulsory the use by bicyclists of special cycling tracks where provided; but whether, before doing so, he will see that those tracks are in every way safe and suitable for the purpose?”

Leslie Burgin replied, again using the word “present,” suggesting that compulsion might one day be introduced: “With regard to the first part of the question, I have no present intention of taking the course suggested. As to the second part, so far as it arises, my Department has recently drawn the attention of all highway authorities to the importance of providing satisfactory cycle tracks.”

Sir Alfred countered, “What is the use of providing these cycle tracks if they are not used by cyclists?”

Burgin: “I think the House will appreciate that there must be a considerable length of cycle tracks before any question of this kind can arise. I sincerely hope that cyclists will progressively use the facilities which are provided for them.”

MPs remained incredulous that cycle tracks were being built at great expense but that cyclists would not be compelled to use them.

“Does the right hon. Gentleman not think that when these cycle tracks are made some steps should be taken to make the cyclists use them?” asked Colonel Sir Charles MacAndrew.

“We must wait until we have a considerable continuous length of tracks before we talk about the obligation to use the track,” replied Burgin.

However, Burgin’s boilerplate answer wasn’t always wheeled out. For instance, speaking in October 1938 about the future of London’s traffic to the Liberal National Forum at the National Liberal Club in London, Burgin let slip that cyclists should be “glad enough” to use the cycle tracks provided. “I think,” he quipped, “that if it is left to me to introduce legislation on the subject there may have to be a whiff of grapeshot in it to see that this is carried out.”

This explosive comment reached the ears of organised cycling, and they sought an urgent audience with the minister.

The Times reported that in December 1938, “the Minister of Transport, Mr. Burgin … assured a deputation from the National Committee on Cycling that there is no immediate likelihood of cyclists being compelled to use special cycle tracks.”

Burgin said he was a cyclist and therefore “had the fullest understanding of the cyclist’s point of view … and there would be no form of compulsion until [cycle tracks] were of adequate length and width and had a proper surface.”

While Ministers of Transport didn’t legislate to compel cyclists to use cycle tracks, government bean counters were very much in favour of the concept.

In 1939, Kenneth Macaulay, chief accountant at the Ministry of Transport, wrote to the Treasury’s F. N. Tribe: “Whilst we can do nothing to stop ‘hordes’ of cyclists using the arterial exits from the large urban centres, I am sure you will agree that everything should be done to keep them off the carriageways, if this can be effected at a reasonable cost.”

Tribe agreed: “There is much to be said for the recommendation that where tracks are provided for cyclists their use should be compulsory … What we dislike is the apparent waste of money on constructing tracks the use of which cannot be guaranteed, especially as it is opposed by certain leaders of the cycling community. We should of course have no object to reasonable expenditure if we could be assured that it was serving a useful purpose …”

In a follow-up letter, Tribe added that he had been “talking to a friend who has recently returned from a visit to Belgium … where the appropriate sign is erected cyclists are required to use the track and to keep off the road.”

SEGREGATION MUST COME

Elsewhere in this study, I have featured Eric Claxton, then a junior engineer in the Ministry of Transport, who, in the 1970s, wrote that the cycle tracks he worked on in London were sub-standard. “As a cyclist, they gave me no satisfaction,” he complained:

They were too narrow. They were made of concrete and suffered from either cracking or construction joints. They provided protection where the carriageway was safe but discharged the cyclists into the maelstrom of main traffic where the system was most dangerous.

Claxton’s managers thought differently. They believed the tracks were of excellent quality and that cyclists should therefore be forced to use them. The Divisional Road Engineer for the East of England wrote to the Chief Engineer in 1935: “It seems to me to be of little use getting more cycle tracks constructed unless it is intended to compel the pedal cyclists to use them …”

Nine years later, a Ministry of Transport report admitted that cyclist opposition “does not arise from a spirit of obstinacy but is largely based on the inadequacy of the cycle tracks so far constructed and the dangers [to] which they give rise.”

Despite this kind of faults, transport ministers and planners at the time ignored the complaints from organized cycling, including a dissenting view on a government-sponsored cycling-specific report. The Report on Accidents to Cyclists took the government’s Transport Advisory Council two years to compile, and when it was published in 1938, it said the UK should be provided with continuous, wide, well-surfaced cycle tracks. And use of these tracks, where provided, should be made compulsory.

The Transport Advisory Council (TAC) was founded in 1934 to examine how to reduce road deaths. The “accidents to cyclists” sub-committee of the TAC was made up of thirteen members, including five Sirs, three Justices of the Peace, but only one cyclist. This cyclist — Frank Urry of the Cyclists’ Touring Club — lodged the only dissenting voice over the provision of cycle tracks.

In the report, he wrote:

I cannot subscribe to the recommendation of extending the building of cycle tracks, or the compulsory use of them by cyclists if and when laid down. The danger of right-hand crossings discounts any presupposed safety obtained by partial traffic segregation; and it has been admitted that where cycle tracks are in being, motoring speeds on the carriageway will increase, to the consequent danger of the cyclists when the cycle track ceases, as it must do on over 95 percent of our highways. Cycle tracks are a palliative at best, and in my opinion a dangerous one.

Nevertheless, the TAC report was accepted by the then Minister of Transport, Leslie Burgin. “The Transport Advisory Council … have now reported and made a number of recommendations,” Burgin told parliament in June 1938.

“Perhaps the most important of these are the building of cycle tracks of a particular type, and, where such tracks are built and are satisfactory, the making of the use of them compulsory.”

Despite the considerable effort in compiling the report, the Transport Advisory Council’s main recommendations were put on hold until a separate report on general road safety was published by a House of Lords committee led by Lord Alness. The March 1939 Report of the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents, generally known as the Alness Report, was heavily biased towards motorists.

“There is much thoughtless conduct amongst cyclists which is responsible for many accidents,” sniffed the report, making 231 recommendations, including that children of ten and under should be banned from public cycling (“children under seven cause 23.9 per cent of the accidents to pedestrians,” claimed the report) and that segregation on the roads should be carried out with utmost urgency.

Cyclists, said the report, should get high-quality wide cycle tracks and that, once built, cyclists should be forced to use them.

In evidence given to the Alness committee, Cyclists’ Touring Club officials stressed that their main objection was to the quality of cycle tracks and not just to the principle of being able to continue riding on the carriageway. The CTC feared that legislation would be brought in that would make it compulsory to use such tracks even before a useable network had been built and that, going by the poor provision of tracks in the previous five years, there was little likelihood that the tracks of the future would be of high quality.

Some older club cyclists might have hankered after the old days — of riding on bucolic country lanes empty of motor traffic — but many of the younger ones preferred to ride on the concrete arterials. The new roads — gleaming white ribbons of modernity — were built for speed.

The new arterial roads might have been busy with motor traffic on holiday weekends, but they were often quiet at other times. In effect, many of Britain’s cyclists felt they had been provided with speedways, and they baulked at the prospect of giving them up to ride on narrow, bumpy cycle tracks where they might have to ride slowly, in single file. Writing in 1943, CTC secretary George Herbert Stancer noted that: “A young lady who overtook me on my last journey [on Western Avenue], and rode with me for a short distance, told me that she had to cover 15 miles each way on her daily trips between home and work, and that she was obliged to keep on the road in order to maintain the necessary speed . . . Resorting to the paths would have slowed her down too seriously.”

Club cyclists also wanted to do what motorists could do: talk to someone beside them. The right to the road also meant the right to ride two or more abreast, yabbering with companions as they rode out fast to some tea-room.

Such behaviour horrified the peers on the Alness committee.

The following exchange between CTC secretary Stancer and his aristocratic interlocutors clearly shows the antagonism between the parties, although the CTC man remained polite throughout.

Lord Alness: “Your Association is, if I may say so, broad-minded enough to regard motor traffic as necessary and proper development?”

Stancer: “Yes, my Lord. Of course, we have grown up with the motor movement and I think that during the whole of that period we have treated it with perhaps more tolerance than we have always received at the hands of the people who have been concerned with motoring.”

Lord Alness: “Is your Club in favour of the provision of separate cycle tracks for cyclists?”

Stancer: “No, my Lord, we are not. Our feeling is that cycle paths at the side of the road do not, in the present circumstances, and never can, provide the same facilities for enjoyable cycling as are provided by our present road system.”

Lord Alness: “I should have thought personally that it would be more enjoyable to cycle on the cycle track on the Great West Road than to cycle on the highway there?”

Stancer: “Those people who are not accustomed to cycling always tell me that and I think that it must be a general view… The fact of it is that the existing experiments in the construction of cycle paths are, I think, most unsatisfactory and they have created a bad impression amongst cyclists.”

Lord Alness: “Assume the track was adequate in dimensions, in breadth, as in Germany, 9 feet let us say, and its surface was good, do you not approve of the experiment at least being made?”

Stancer: “On most of them even if we had a sufficient width and an excellent surface there is still the disadvantage that the track by the side of the road is constantly being interrupted and broken by the passage of other tracks coming from houses or whatever it may be. Every time there is a private house with a garage or there is a filling station or there is a way into a field or way into a shop … everything has to come across the cycle path; so that while on the carriageway you get a perfectly straight, smooth, unbroken, uninterrupted course for whatever vehicle is using it, the cyclist has always got something coming across.”

Lord Alness: “But he is not submitted to the same dangers as when he is cycling on the highway on the Great West Road?”

Stancer: “No, my Lord. My suggestion is that those dangers ought to be removed.”

Lord Alness: “Is that not a counsel of perfection? The removal of the dangers seems rather idealistic?”

Stancer: “The other alternative seems to be a counsel of despair: “The law is powerless to preserve you on the road now; you must get off the road.” That is roughly what it comes to.”

“Segregation Must Come” was the title of one of the main sections of the Alness Report of 1939, referring to cycle tracks and barriers on roads to “protect” pedestrians. Cyclists, concluded the report, should get high-quality cycle tracks and must be forced to use them. Pedestrians were also to be fined for daring to cross the road at points other than designated crossing points.

The House of Lords committee published its findings in March 1939; war was declared in September. The Alness Report — derided by one Labour MP as a “tale of deaths and manglings … and extraordinary conclusions” — was moth-balled.

Nevertheless, planning for more roads and adjacent cycle tracks continued during the war years.

“I do not think this is the time compulsorily to exclude pedal cyclists from carriageways of, and to compel them to use the cycle tracks on, those lengths of road where cycle tracks have been constructed,” wrote the Ministry of Transport’s chief engineer in 1941, adding “at the present time the total length of cycle tracks is approximately 200 miles. When cycle tracks have been provided on a more extended scale we can hope their advantages will be apparent to the general body of pedal cyclists, with the result that the enforcement by the police of compulsory power will not then present [a] measure of difficulty.”

Police powers had already been used to “advise” cyclists to use cycle tracks when provided. In June 1938, a National Cyclists’ Union member lodged a complaint claiming that “while cycling on the new Southend road, he was stopped by police officers and lectured for a quarter of an hour because he was not using the cycle path. … On the return journey, the cyclist was warned twice, was given another lecture, and, although admitting that he had been riding properly, officers demanded that he should ‘get off the road’ and ride on the track.”

This claim was backed up by a report in the Western Daily Press which stated that “cyclists, two and three abreast, were a distinct impediment to the traffic” and that a “police loudspeaker coaxed them all onto the tracks as soon as they were reached.”

Government ministers may have said in the 1930s and into the 1940s that they didn’t wish to compel cyclists to use tracks “at present” or “immediately,” but by 1949, the official UK position was for compulsion. The UK was one of the seventeen national signatories to the United Nations Convention on Road Traffic of 1949.

This convention had only three rules for cyclists: that they “shall use” cycle tracks, that they should ride in single file (unless national rules stipulated otherwise) and that cyclists should not be towed by vehicles. In the road-sign part of the document it was agreed that “COMPULSORY CYCLE TRACK … shall be used to indicate that cyclists shall use the special track reserved for them.”

UNFIT

One of the defining characteristics of major infrastructure building is the “lock in … of a certain project concept at an early stage, leaving analysis of alternatives weak or absent,” stated economic geographer Bent Flyvbjerg in 2009 in his classic paper Survival of the Unfittest: Why the Worst Infrastructure Gets Built. He claimed that policymakers had an innate tendency to choose the worst possible projects because of “strategic misrepresentation.” Politicians and planners are often guilty of building the wrong infrastructure, and no evidence to the contrary deflects them from their original decision.

That was certainly the case in creating Britain’s putative, pre-war cycle track programme. Ostensibly built to “save cyclists’ lives,” most of the cycle tracks were built alongside short stretches of out-of-town by-passes, which few everyday cyclists would have needed or wished to use and, consequently, where few lives would have been saved.

Protection for cyclists was needed instead at junctions in built-up areas, and the government was frequently advised of this fact. “The benefit of the cycle-track is lost at the intersection (just where traffic segregation is most needed),” stated an influential planning publication in 1937.

Expensive clover-leaf intersections for motorists could be designed and budgeted for in the late 1930s, but similar intersections for cyclists would be “impossible” or “too costly,” town planners told the six peers on the Alness committee. In evidence given to the committee, witness after witness — from surveyors to arch motorists — attested to the often dire nature of Britain’s first cycle tracks, but, apart from cyclist witnesses, most wanted cyclists to be forced to use them.

In 1944, a government minister promised that at “important road junctions we shall have two-level roundabouts by which cyclists and pedestrians will each have their own means of passing in complete safety wholly segregated from the motor traffic on the road,” but this pledge was not kept.

Despite public and private claims from ministers, mandarins, and planners that they were motivated by a desire to stem the numbers of cyclists killed on Britain’s roads it seems as clear today as it was to cycle organisations of the 1930s that officialdom was, in fact, greatly more motivated by the desire that roads, especially the new and “fast” new arterial roads, should be freed of slow-moving vehicles; motor cars were modern, cyclists and horse-drawn vehicles were not.

Cyclists dominated many of Britain’s trunk roads at this time, and there was a firmly held conviction that cyclists should be barred from the carriageway in the belief that motorists would then be able to drive faster. Most ministers, mandarins, and planners of the 1930s were enthusiastic motorists, and few to none were everyday cyclists.

Some modern cycle advocates suggest it was the opposition of cycling organisations to the cycle tracks of the 1930s that prevented the widespread roll-out of these tracks. A typical claim is that if only the Cyclists’ Touring Club and others had supported the first cycle track, a genuinely Dutch-style cycle network might have later evolved. This does not fit with the evidence. Ministers and mandarins, as well as many powerful and influential organisations, did want such a network of Dutch-style tracks to be built, and — despite opposition from cycling organisations — 100 or so schemes were completed. It was not campaigning from cycling organisations that stopped building more, but the coming of war.

It could be claimed that the government ignored the CTC — which had only 34,000 members in 1939 — because it was catering, instead, to the nation’s twelve million “ordinary” cyclists, but if so, planners would have been instructed to build protective infrastructure where most cyclist deaths occurred, and that was in congested urban areas.

When officialdom discussed obligatory use of cycle tracks, there was much use of loaded caveats such as “there are no present plans” — but this was dog-whistle messaging that once a certain mileage of tracks had been built, the government would bring in continental-style compulsion.

Stancer told the peers on the Alness committee that compulsion was only necessary because cyclists were being fobbed off with an “inferior article.”

It’s worth reiterating that the CTC man stressed: “If the paths are by any miracle to be made of such width and quality as to be equal to our present road system, it would not be necessary to pass any laws to compel cyclists to use them; the cyclists would use them.”

Stancer’s argument was obstructively utopian — he and the peers knew there was no chance of making cycle tracks as wide and as extensive as Britain’s existing roads. Today, many cycle advocates consider that Stancer, and other representatives of organised cycling, ought to have welcomed the first cycle tracks with open arms.

It’s easy to take such a position with hindsight; we have forgotten how dominant cyclists were on the roads in the 1930s. Today, many cyclists welcome provision of protected cycle tracks and feel it only fair that at least a portion of the road should be set aside for cyclists, but in the 1930s and 1940s, cyclists, in effect, ruled the roads. They were being told that their time in the sun was over, they would instead be forced to ride on much narrower infrastructure, where surfaces might not be as smooth and where cyclists had to give-way at the growing number of side roads. Forcing the majority users of the roads onto inferior infrastructure was seen at the time as a major loss of amenity by those on the receiving end.

Back then, when the number of cyclists was high, using narrow cycle tracks greatly reduced cycling’s utility. Today, when the number of cyclists is very low in comparison, it’s hoped that the provision of protected cycleways will encourage more people to cycle. It’s instructive that officialdom in the 1930s had no desire to encourage cycling’s growth; in fact, the aim was very much the opposite.

And today? Apart from the pledge to “transition to zero-emission driving” the other key aims in the UK government’s October 2023 Plan For Drivers could have been written in the 1930s, urging as it does “smoother journeys” (for that read “faster journeys”) and setting out how “government is working to improve the experience of driving and services provided for motorists.”

Plus ça change.

NOTES

[1] The Cyclists’ Touring Club was founded in 1878 and – like cycling itself prior to 1920 – was elitist. As I recount in Roads Were Not Built for Cars (Island Press, 2015) the elite worlds of cycling and early motoring were intimately linked. For instance, Ernest Shipton, CTC secretary in the early 1900s, was also a board member of the Automobile Association. And CTC’s later secretary G.H. Stancer was also a car owner.

[2] There’s little to no evidence that this occurs on the roads in the Netherlands.

[3] A giant two-level roundabout was constructed in Utrecht from 1941 to 1944 – it kept cyclists and motorists apart. The “Berekuil” – or “Bear Pit” – had been designed in 1936, and is still in use today, although it has been modified over the years. This is the sort of infrastructure that, in the same period, the British government said would be too difficult and too expensive to build for cyclists in England. See: http://www.usine-utrecht.nl/rijkswegenplan-1936-verkeersplein-berekuil-waterlinieweg

A grade-separated roundabout to aid motorists, and supposedly protect pedestrians, was built in 1939 on the A22 Caterham by-pass – the Wapses Lodge roundabout was way ahead of its time, and quite the eyesore today, so it must have looked incredibly alien in 1939.2 Pedestrians rarely use the underpasses. At the beginnings of the 1960s, a number of similar grade-separated roundabouts for pedestrians and cyclists were built in Stevenage – they were modelled on the Berekuil. See: https://goo.gl/maps/G3vMKRj6F7H2 ; http://www.caterham-independent.co.uk/features/2655-wapses-lodge-roundabout-a-local-history-article-by-ruth-sear .

[4] A 1935 pamphlet produced by the Cyclists’ Touring Club and titled Road Safety: a fair and sound policy stated: “It is often said that there is not room on our present roads for everybody and so the cyclist should be removed. The only traffic that cannot safely use our present roads is high-speed motor traffic, for which special highways should be provided.”

[5] The Local Government Act of 1929 made county councils responsible for the building – and maintenance – of main roads.

[6] Oliver Stanley, Conservative – 22nd February 1933–29th June 1934

Leslie Hore-Belisha, National Liberal – 29th June 1934–28th May 1937

Leslie Burgin, National Liberal – 28th May 1937–21st April 1939

Euan Wallace, Conservative – 21st April 1939–14th May 1940

John Reith, National Independent – 14th May 1940–3rd October 1940

John Moore-Brabazon, Conservative – 3rd October 1940–1st May 1941

Frederick James Leathers, 1st Viscount Leathers, Conservative – 1st May 1941–8th October 1944

[7] The Rainford bypass was designed in 1937 with the middle section constructed by the outbreak of WWII. However, the rest of the road wasn’t completed until 1950. The cycle tracks and the road were surfaced with asphalt rather than concrete as was common in the 1930s.

[8] Brits cycled 14.2 billion miles in 1952. This dropped to 7.5 billion miles by 1960, and was 3.4 billion miles by 1967. It is roughly 3.2 billion miles today, and has been about that since 2009. (See: “Pedal cycle traffic (vehicle miles / kilometres) by vehicle type in Great Britain, annual from 1949,” Department for Transport statistics, http://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-transport/series/road-traffic-statistics .) These are average stats for the whole of the UK. There were pockets of high cycle usage, and not just in places such as Cambridge but also Hull, York, March and others. Even as late as the 1968 census cycling usage remained remarkably high in those towns.

“Cycling levels have shown long-term decline since the 50s. Between 1952 and 1970 annual distance cycled fell from 23 billion kilometres (13% modal share) to 5 billion kilometres (1% modal share),” See: *Urban Transport Analysis,” Cabinet Office Strategy Unit, 2009.

Cycling levels fell off the proverbial cliff in 1949, and this has been tracked in oral history and diary research, too. Colin Pooley and Jean Turnbull interviewed or analysed the writings of thousands of Brits, tracking their use of getting to work. By the mid-1930s “approximately one fifth of men cycled to work, and around one tenth of women.” (See: Pooley, C., and J. Turnbull, “Modal choice and modal change: The journey to work in Britain since 1890,” *Journal of Transport Geography*, 2000.)

[9] The next UK attempt to “Go Dutch” was implemented in Stevenage, 30 miles north of London. From the get-go in the 1950s this New Town was laced with a gridded network of 12-ft-wide cycleways, on separate alignments to roads. Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, Stevenage was held up as proof that the UK *could* build a Dutch-style cycle network.

Stevenage’s 1949 master-plan projected that 40 percent of the town’s residents would cycle, and just 16 percent would drive. The opposite happened. By 1964, cycle use was down to 13 percent; by 1972, it had dropped to seven percent. It’s now less than three percent. See: roadswerenotbuiltforcars.com/stevenage

[10] See: “How the Dutch Really Got Their Cycleways”, Bike Boom, Carlton Reid, Island Press, 2017.

[11] Separating cyclists from other traffic with a kerb does not banish them from the highway. The “public highway” is the full width of the highway, including carriageways, footways, verges and the like. This opinion was given to the peers on the Alness Committee in 1938 by D.H. Brown, County Surveyor of Warwickshire (who was in charge of constructing the Coventry By-pass with its cycle tracks on both sides of the road): “Engineers look upon the highway as the whole width between the forecourt fences, i.e. the the outside boundary wall or the front wall of the houses. We do not draw a distinction like the cyclists do, that they are are driven off the highway if they are driven off the carriageway … We believe that the expense of putting [cycle] tracks down in a proper way – and they are of no use if they are not serviceable – is so great that the use of them when they are made should be compulsory…As engineers we cannot understand the attitude of the cyclist who will not ride on the special track provided…the cycle track is part of the highway.” ACCIDENTS: House of Lords (Lord Alness) Select Committee on Road Accidents; Ministry of Transport evidence and memorandum on Report, 1938-1939

[12] Today the word “carriage” suggests a four-wheel vehicle pulled by horses, and succeeded by cars, or “motor carriages” and therefore the “carriageway” is dedicated to such usage. However, up until late in the 19th century the word “carriage” meant the act of carrying, and could be applied to, say, a pack animal. The Imperial Dictionary of 1854 defined “carriage” as “the act of carrying”. The carriageway is therefore part of the highway where passage is allowed and where carrying may or may not be involved.

[13] The Cyclists’ Touring Club formed a committee to oversee the progress of the Local Government Bill through Parliament. It was feared that if County Councils were given powers to create their own bye-laws such bye-laws would be used to prohibit the riding of cycles. The CTC had political clout: it asked one of its MP members to lodge an amendment to the Bill. Sir John Donnington “won a brilliant victory for the Club,” wrote James Lightwood, the author of a 1928 history of the CTC. The Romance of the Cyclists’ Touring Club, J.T. Lightwood, CTC, 1928

[14] James Lightwood, author of a 1928 history of the Cyclists’ Touring Club, said of the Act:

“As a result there disappeared … every enactment which gave to Courts of Sessions, Municipal Corporations and similar bodies in England and Wales power to resist and hamper the movements of cyclists as they might think fit. The new order of things established once and for all the status of the cycle.”

The Romance of the Cyclists’ Touring Club, J.T. Lightwood, CTC, 1928

[15] While the 1888 Local Government Act formalised the right to cycle on British roads it was preceded and informed by a court case from 1879, the year after the foundation of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. The case of Taylor v. Goodwin was heard by Mr. Justice Mellor and Mr. Justice Lush, sitting in banco in the Queen’s Bench Division, and it held that bicyclists were natural users of roads and therefore liable to the pains and penalties imposed by the 1835 Highway Act which defined acts of “furious driving”.

The case had been brought against a Mr Taylor who had been charged for “riding furiously” down Muswell Hill in London, knocking down a pedestrian in the process. His defence argued that as a bicycle wasn’t defined as a carriage in the 1835 Act there was no case to answer. The plea was disregarded and Taylor was fined. The case was appealed and justices Mellor and Lush ruled that bicycles were henceforth to be considered carriages under the law.

This was bad for Taylor, good for cyclists in general. It meant bicycles, for the first time, had a legal status. Described as carriages, they had full legal rights to pass and repass along highways.

Incidentally, in Taylor v Goodwin the bicycle was defined as “a double wheel” by Justice Lush, but “it carries man”; while Justice Mellor called it “a compound of man and wheels — a kind of centaur.” Taylor v Goodwin, 1879. 4 QBD 228.

[16] “The Roads Improvement Association has recently revived the suggestion to provide special tracks for cyclists on the more congested main roads.” Daily Herald, August 10th, 1922. See also: Roads Were Not Built for Cars, Carlton Reid, Island Press, 2015.

[17] “This movement should be resisted by all the power of the cycling community. Cyclists now number a considerable proportion of the total victory strength of the country and if they speak with no uncertain voice on this matter at political meetings they will be listened to.

“Cyclists and Special Tracks”, Daily Herald, May 10th, 1929.

[18] Opposition to cycle tracks from the Cyclists’ Touring Club continued until the 1960s when club officials warmed to the Dutch-style cycle tracks then being built in Stevenage. Opposition started again in the late 1970s and continued until c. 2012.

[19] From 1912 to 1934 the county surveyor for the County Council of Durham conducted traffic surveys on the busy A1 Great North Road at Framwellgate Moor and Teams Crossing. This survey showed that even on a road increasingly dominated by motor vehicles there was a doubling in bike use in the 1930s, and this was one of the reasons for the creation of cycle tracks beside new bypasses, dual carriageways and other “arterial roads.” In 1935, the county surveyor wrote:

“Generally, the statistics show an increase in lorry traffic and in motor cars, together with ordinary cycles … This year ordinary cycles have more than doubled in number the figures recorded two years ago. In this mind the committee will have in mind the recent circular of the Ministry of Transport regarding the provision of cycle tracks along the main roads . . . There is no doubt whatever . . . that the question of handling the problems created in highway administration is of great importance in the life of the community.”

Pedestrian traffic was not recorded.

Report of the County Surveyor to the Works Committee, January 21st, 1935, County Council of Durham.

[20] For instance, Chatham dockyards, 1939. See: http://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/general-view-of-cyclists-arriving-for-work-at-chatham-news-photo/3312800?#circa-1939-a-general-view-of-cyclists-arriving-for-work-at-chatham-picture-id3312800

[21] Making the Roads Safe: The Cyclists’ Point of View, Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1937.

[22] Pedestrians were not counted.

[23] Kuklos, Daily Herald, September 12th 1936

[24] Making the Roads Safe: The Cyclists’ Point of View, Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1937.

[25] Making the Roads Safe: The Cyclists’ Point of View, Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1937.

[26] The Standard Motor Company later made Triumph cars including the much-loved Triumph Herald. The company had a number of factories in Coventry, including at Canley which is just off the A45 Fletchampstead Highway. There are long stretches of high-quality 1930s cycle tracks beside the A45. There is a now a large Sainsbury’s supermarket on one of the main factory sites. https://goo.gl/maps/wYcL6CkHxt62 Undoubtedly many workers would have ridden to the factory via the cycle tracks. The Canley factory also made1,000 dMosquito figheter-bombers during WQWII.

Death On The Roads, John Paul BLACK, later Sir, The Times, October 12th, 1935.

[27] CVM was founded in 1931 and had 34,000 members. It was renamed the Guild of Experienced Motorists in 1983 and now, as GEM Motoring Assist, provides breakdown services to motorists.

Lord Howe: “What about cycle tracks?

[28] The RAC’s solicitor Corris William Evans told the Lords that “the Club considered that restrictions on motorists were sufficient, and that the penalties provided for motoring offenders were adequate …”

“Restrictions On Cyclists,” The Times, April 13th, 1938

[29] “Protection for Cyclists,” The Times , June 21, 1938

[30] The Times, April 4th, 1934. George Herbert Stancer was secretary of the Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1920-45. He wrote in the CTC’s Gazette under the pen-name “Robin Hood”. His columns gave a “vigorous defence of cyclists against repeated attempts by motoring interests to encroach on their freedom and welfare,” said William Oakley in Winged Wheel, Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1977. Stancer wrote an article in 1946 in Cycling entitled “The Fallacy of Cycle Paths”. According to Oakley this “recorded what had happened on the Continent when cyclists had lost the right of choosing to ride on the carriageway or the cycle path.” However, this also shows that people were still cycling on cycle tracks, because Stancer was complaining about these tracks in 1946.

[31] A later and more personal epithet was a “Belisha cycle-pen.”

“Pedalling in the Far North,” Kuklos, Daily Herald, October 19th, 1935

[32] “Compulsory use of cycle-paths? Let them beware! The paths are quite inadequate to carry holiday and rush-hour traffic – their width should have been added to that of the highway.

“I foresee traffic blocked by the crowds of cyclists waiting for access to the little paths, and police megaphones urging them to break the law and the the highway!”

Kuklos, Daily Herald, 26 March 1938.

“Since the Minister of Transport has ignored the protests of organised cyclists in the matter of his leper-paths, and since the voice of organised cyclists is not loud and insistent enough, a strong attempt at last being made to let the Minister have a protest a truly national scale.

“So an Open Letter the National Committee on Cycling has been drawn up, signed by influential and well known officials and members of the CTC. and National Clarion, and is now circulating amongst the clubs. These asked to pass resolutions in support of the Open Letter and send them to the secretary of the National Committee. Mr Williamson. 10. Adam-street, London. W.C.2

“The only interest of the who include myself is the successful conclusion of the campaign to make the King’s Highway for ever free to all road-users.

“Pointing out that Mr. Hore-Belisha would like to make 4,500 miles of compounds or concentration camps for cyclists along the trunk roads now under his administration, the Open letter which is being circulated by the West of Scotland Cyclists’ Defence Committee, calls for firm and decisive leadership from the National Committee. and that committee the Open Letter makes five positive suggestions.

“1 – That the Committer shall draft, and cause circulated, a petition to the Minister, drawing attention to the grievances of cyclists. The aim should be to secure a million signatures to this document

2 – That the Committee shall proclaim national cyclists’ Day of Protest. when simultaneous mass rides would held in every large centre in Britain

3 – That the Committee shall organise the systematic lobbying MP s. and shall provide material to assist clubs to take up the case with their local members and councils.

4 – That the Committee institute a nation-wide press campaign enlighten the general public the facts upon which cyclists take their stand.

5 — Under the leadership the Committee. the local centres of the C T C . N.CU. and Clarion asked take the initiative in establishment of local Cyclists’ Defence Committees on the lines those in the West of Scotland and Southampton, for the conducting local protest rides.

“It is urged that the Minister of Transport must shown that cyclists have not retreated from their position, out are as determined as ever to resist bv all possible means the forcing of cyclists into the compounds, and other such repressive measures.

“I begin to suspect, however, that Mr Hore-Belisha is not a free agent.”

Kuklos, Daily Herald, 13 February 1937.

[33] Cyclists, avoid those “Special Tracks” , Kuklos, Daily Herald, 17th February 1934

[34] Protest Against Cycle Tracks.

The Times, January 12, 1935

[35] J. GILBERT WIBLIN, 26 Hamilton Road, Oxford. Tracks For Cyclists. The Times, August 31st, 1935

[36] Anfield Bicycle Club Monthly Circular, January 1935. The club was formed in 1879. William “Billy” P. Cook, president of the Anfield Bicycle Club and vice-president of the Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1924-1936, was the cyclists’ representative member of the Advisory Council to the Minister of Transport in the mid-1930s.

[37] “More than 500 cyclists … cycled along the main road in club formation, and ignored the cycle path. . . . Earlier there was a meeting of the cyclists in Hyde Park at which a resolution was passed calling on the Minister for Transport not to proceed further with cycle paths, on the ground that cyclists had an equal right with others to the King’s highway.” ”News in Brief,” The Times, August 26th, 1935.

[38] At the trade show of the Hercules Cycle Manufacturing Company held to-day at the Piccadilly Hotel. Sir Edmund Crane, chairman of the company in an address of thanks to Viscount Dunedin for opening the exhibition, made vigorous protest against the introduction of special cycle tracks the Ministry of Transports new scheme. Sir Edmund, who said that, as chairman of the largest cycle manufacturing concern in world, he knew the minds cyclists on the question, baaed his protest the principle mad freedom for all kinds of traffic. He believed that the cycle path would mean the exclusion of cyclists from the rest the road, and would Inevitably mean that cyclists would be forbidden to use the roadways in towns and cities. As the great majority of cycles were used for utilitarian purposes, any restriction their right to use the public highway would certainly affect the national prosperity. He foresaw a system of cycle taxation being introduced for the upkeep of the special tracks which cyclists did not desire. Sir Edmund put forward the suggestion that much of the £100,000,000 which is to be spent on the roads should devoted to the construction of motor ways on which the motorist could travel at unlimited speed, and from which slow traffic should excluded. He would not. however, prohibit motorists using other roads at a limited speed.

Yorkshire Evening Post, 2 December 1935.

H. R. Watling, director of the British Cycle and Motor-cycle Manufacturers and Traders Union, voiced his fear at one of the Alness committee hearings: “I think cyclists in general fear that if cycle tracks are provided in certain places the psychology of the motorist will be affected adversely . . . they will regard the cyclist as more and more an undesirable person on the road, and it may lead in some cases to an increase in the degree of carelessness exhibited by drivers of all types.”

[39] See: http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1934/nov/07/cyclists-regulations#S5CV0293P0_19341107_HOC_169

[40] In 1922, just before the start of a working-class bicycle boom, Hercules was making 700 machines a week. By the mid-1920s, a bicycle could be bought new for what the average labourer earned in two weeks – it was becoming an affordable luxury. By cutting prices even further, and advertising the fact, Hercules sold 300,000 bicycles in 1928. Five years later this had risen to 3 million sales per year. At the end of the 1920s, while manufacturers such as Raleigh continued to make and market bicycles for touring and leisure use, Hercules mostly made utilitarian bicycles. A Hercules bicycle was a workhorse, cheaper than its rivals, but still reliable. In 1939, Hercules made 6 million bicycles, making it one of the largest cycle manufacturers in the world.

Hercules was later bought by Raleigh.

“Lord Nuffield Cycles To Open Olympia Show”, Daily Herald, November 1936.

[41] *Making the Roads Safe: The Cyclists Point of View. Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1937. The pamphlet added: “Whenever the cycle path came to an end the riders on it would have to find a place in the traffic on the carriageway, and, of course, that traffic would be ‘running with confidence’ and not expecting to make way for cyclists.

“The provision of some roads with cycle paths would naturally confirm inconsiderate motorists in a false belief that they need have less regard for other classes of road users. Driving would become faster and more reckless on all roads, including the majority of road that could not be provided with cycle paths.”

This fear wasn’t without some merit, in the UK at least. Modern-day cyclists are often told by motorists to “use the cycle path provided” even when the cycle path is poor. The situation is different in the Netherlands – Dutch motorists do not shout at cyclists riding bikes on Dutch roads that do not have cycleways (although they may do if the roads do have cycleways).

[42] “Are Cyclists’ ‘Lanes’ Practicable?” G.H. Stancer, Cycling, 1943

[43] 1946: “If there is a cycle track – use it.”

1954: “If there is an adequate cycle track, use it.”

1968: “If there is an adequate cycle path beside the road, ride on it.”

1978: “If there is a suitable cycle path, ride on it.”

Want to hear in plain song? The Master Singers recorded “The Highway Code” in 1966. It’s rather beautiful. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o7vykx5_e1s HT to Mike Prior-Jones

[44] Letter from G.A. Olley, March 11th, 1935, champion cyclist, quoting D.E. O’Neill, Hore-Belisha’s private secretary. CYCLE TRACKS: Proposed construction, 1926-1943, Ministry of Transport, MT 39/127, National Archives, London.

[45] House of Commons debate, February 7th, 1934.

[46] Letter to E. Ashley Dodd, Carlton Club, London, by Aubrey Clark, private secretary to Minister of Transport, Leslie Hore-Belisha, 26th September 1934. CYCLE TRACKS: Proposed construction, 1926-1943, Ministry of Transport, MT 39/127, National Archives, London.

[47] Speech given by Minister of Transport Leslie Hore-Belisha at opening of Cycle and Motor Cycle Exhibition, Olympia, London, 1934, 5th November 1934. The Cyclists’ Touring Club wrote to Hore-Belisha, complaining about his statement:

“ …the Cyclists; Touring Club protests against the remarks of the Minister of Transport on the subject of cycle paths, made at the opening of the Bicycle and Motor Cycle Show, and would remind Mr. Hore-Belisha that cyclists are opposed to the idea of such paths and are not prepared to give up their inalienable right to use the public highway …”

Letter to the Minster of Transport from Cyclists’ Touring Club, 3, Craven Hill, London, November 20th 1934.

Photo of Hore-Belisha on a Raleigh tandem at the 1935 show. He rode a tandem together with Sir Harold Bowden, the chairman of the Raleigh Bicycle Company. London. https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/british-politician-leslie-hore-belisha-the-minister-of-news-photo/818848700#british-politician-leslie-horebelisha-the-minister-of-transport-on-a-picture-id818848700

[48] Letter to Leslie Hore-Belisha from Mr. P. J. H. Hannon MP, February 8th 1935.

[49] Editorial, C.T.C. Gazette, January, 1935.

[50] Letter to transport secretary Leslie Hore-Belisha, 16th February, 1935, from Sir Charles Granville Gibson, Conservative MP for the Pudsey and Otley division of the West Riding of Yorkshire.

[51] Mr. PALING If cycle tracks are provided, is the use of the main road prohibited to cyclists?

Mr. HORE-BELISHA No, not yet.

CYCLE TRACKS.

HC Deb 03 July 1935

[52] Letter from D. E. O’Neill, private secretary to Minister for Transport Leslie Hore-Belisha to G. A. Olley, 127 High Road, Southampton, 20th February 1935. CYCLE TRACKS: Proposed construction, 1926-1943, Ministry of Transport, MT 39/127, National Archives, London.

[53] Letter from D. E. O’Neill, private secretary to Minister for Transport Leslie Hore-Belisha to G. A. Olley, 127 High Road, Southampton,

2nd March 1935. CYCLE TRACKS: Proposed construction, 1926-1943, Ministry of Transport, MT 39/127, National Archives, London.

[54] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_Locker-Lampson

[55] Letter from Minister of Transport Leslie Hore-Belisha to Commander O. Locker-Lampson, CMG, DSO, MP, House of Commons, 12th March 1935. CYCLE TRACKS: Proposed construction, 1926-1943, Ministry of Transport, MT 39/127, National Archives, London.

[56] “Cycle Tracks”, House of Commons debate, 9th June 1937.

[57] Sir C. MacAndrew: “Is the right hon. Gentleman aware that where there are cycle tracks they are very largely not used by cyclists?”

Mr. Burgin: “That is so, but there are not yet continuous cycle tracks which will permit of the matter being dealt with comprehensively. I hope that every encouragement will be given to cyclists to use the cycle tracks, and I am anxious that long and continuous cycle tracks should be made available before we go into the matter on a large scale.”

East Ham And Barking By-Pass (Cycle Tracks), House of Commons debate, 16 June 1937.

[58] “On London Traffic,” The Times, October 20th, 1938.

[59] “Cycle Tracks,” The Times, December 6th, 1938.