WHO PUSHED FOR CYCLE TRACKS?

It’s not fanciful to imagine that most period motorists —predominantly still wealthy elites at this time — wished for their mechanised amenity to be aided by moving slower users from roads. Many explicitly stated such a desire in letters to the press and the Ministry of Transport. Numerous influential individuals and organisations lobbied lawmakers for the same thing, typically framing this desire as a safety concern for the cyclists, pedestrians, and horse-drawn vehicles deemed to be impeding the new “owners of the road.”

Little thought was given to where slower road users should go except that they should be almost literally sidelined. Pedestrians were expected to stick to footways and now cross roads only at designated crossing points (transport minister Leslie Hore-Belisha was photographed trialling road crossings where pedestrians were penned in by chains, like cattle, with police officers opening and shutting gates). Horse-drawn traffic was anticipated to reduce as haulage companies motorised. Cyclists, however, remained a problem. There were ten or perhaps twelve million by the end of the 1930s (and only two million or so motorists.)

Cyclists were faster than pedestrians and horse-drawn vehicles but slower than motorists. Many in power saw placing these problematic road users on protected infrastructure as an obvious move. However, they sometimes begrudgingly acknowledged that the sheer numbers of cyclists would make such corralling almost impossible at peak times.

Despite such difficulties, many influential individuals and organisations stated they wanted the use of cycle tracks to be made compulsory, and some explicitly admitted this was to reduce the amenity of cycling, a form of transport deemed by many individuals and organisations to be dated.

Cycling bodies frequently and loudly griped that providing period cycle tracks was to deter cycling, not provide safety.

The Cyclists’ Touring Club (CTC) and other cycle organisations — led by the same kind of elites in charge of motoring organisations — might have represented the majority of period British road users, but this cut little ice with lawmakers.

Motoring was deemed to be the transport mode of the future, and any dissenting views were dismissed. Giving evidence to the 1938-1939 Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents, CTC secretary G. H. Stancer exasperated the motoring-fixated peers on what was known as the Alness Committee. The peers assumed cyclists wanted to maintain their hard-won highway rights. Still, Stancer pointed out that it was the inferiority of the new cycle tracks that was the more pressing concern and that the compulsion to use such inferior infrastructure was anathema.

“Cyclists would never insist upon their abstract rights [to the highway] if it were not that they are losing the chief pleasure of cycling by being forced onto the paths,” he told the committee, to the annoyance of the peers.

If, he stressed, “the paths are by any miracle to be made of such width and quality as to be equal to our present road system, it would not be necessary to pass any laws to compel cyclists to use them; the cyclists would use them.”

Some of the organisations below also gave evidence in front of the Alness committee; all were in favour of cycle tracks, with only the Automobile Association advocating for greatly improved infrastructure for cyclists.

Automobile Association (AA) bike patrol

AUTOMOBILE ASSOCIATION

The Automobile Association was very much in favour of the 1930s cycle tracks programme, as shown by a transcript of deputy secretary Edward Fryer giving evidence to the Alness Committee.

Fryer: “The cycle tracks on the Great West Road are not only too narrow but they were too rough, they were too full of manholes, there were too many crossings where the cyclist had to go up and down … Our submission has been for many years that if special tracks are made, they should be of the right type, so as to attract the cyclist. The width of the cycle track should be 12ft … excepting where cycle tracks are provided for big works, 12ft would be insufficient … under the existing law, the cyclist and the pedestrian cannot be excluded from the King’s Highway.”

Lord Alness: “If the cycle track is there, and is of suitable dimensions, and the cyclist deliberately neglects to use it, and uses the carriage-way instead, would you favour the imposition of a penalty?

Fryer: “I think it must come.”

Fryer also went on to show a diagram of a road of the future, which included Dutch-style cycle underpasses. “The [cyclist] would pass under the carriage-way, come up on to the bank and join the other cycle track which goes continuously along the arterial road.”

AA recommended taking 300ft for designing such roads, giving plenty of space for the anticipated rise in motor traffic and protected tracks for cyclists and pedestrians. “You can get complete segregation of these three kinds of traffic…[but] it requires more land…more land than is the present policy of the Minister of Transport.”

“[Where] cycle tracks and footways are sometimes going over and sometimes going under, if you are going to continue to have those at a reasonable gradient, looking to the future, instead of being really steep, it does require this extra width for getting into the swing.”

Lord Alness: “A considerable time must elapse before all the road junctions in the country can be redesigned and reconstructed?”

Fryer: “We appreciate that.”

Lord Alness: “But if you are going to make it compulsory, you get the possible weekend time when between large towns you have droves of cyclists…”

Fryer: “[By] that time I hope that the extra provision of land by the side of the roads, and in certain cases even footpaths, may be used as cycle tracks…[so] the carriageway is left free for vehicular motor traffic.”

This transcript, and others below, is from a 622-page appendix containing expert witness statements given in the Report by the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents, more commonly known as the Alness Report, 1939.

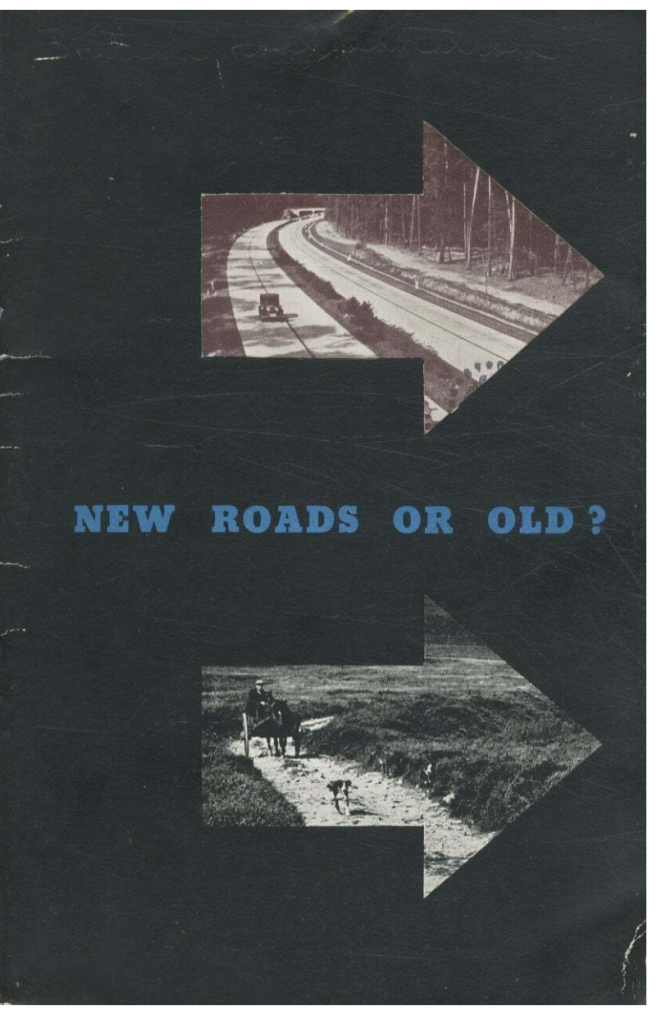

BRITISH ROAD FEDERATION

The British Road Federation (BRF) was a pressure group founded to contribute to the 1932 report of the Salter Conference on competition between road and rail. Its members included various trade associations representing thousands of firms and was helped into being by the AA and the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders.

Its main objectives were to “promote, watch over and protect the interests of all persons concerned in the construction or in the use of roads” and to “generally to protect the interests of all road users.”

In practice, the BRF lobbied for motor interests alone. It was a staunch supporter of cycle tracks.

In a 1937 pamphlet, the BRF insisted “that new roads must have dual carriageways of 30 ft apiece … and cycle tracks within five miles of towns and along the whole length of trunk roads.”

The pamphlet also advocated for bridges and subways for pedestrians. “Pedestrian pavements on the first floor is another plan put forward,” reported The Scotsman. (Such “walkways” in the sky were built in London, Leeds, Newcastle, and other cities in the 1960s and 1970s; they were unpopular, little used, and consequently, few remain extant.)

Gresham Cooke, secretary of the British Road Federation, gave evidence to the Alness committee.

Lord Howe: “Do you advocate, where it is possible, the construction of special cycle tracks?”

Cooke: “I certainly do, my Lord.”

Lord Howe: “Do you further advocate their compulsory use by cyclists?”

Cooke: “Yes, my Lord, certainly … I should like to see it made an offence where a cycle track exists and where it is in a proper state. There is a great deal of criticism of cycle tracks and the state in which they are, but where they exist, we certainly urge that it should be an offence not to use them.”

Lord Howe: “Do you happen to know whether this is so in Germany? One’s observation is that one almost never sees a cyclist on the highway, but always on the cycle track.”

Cooke: “Both in Germany and in Holland which is another densely trafficked country, where there seem to be many cycles per thousand of the population, you find everywhere that the cyclist keeps very closely to the cycle path, which is a far less satisfactory path than in this country.”

The British Road Federation was noted for its academic approach to road lobbying, impressing local and national politicians with studious reports. In 1939, it commissioned a “large working model of a modern road system” with “miniature cars and other motor vehicles … seen in motion upon it at different speeds.”

“One of the main features of the model is a special motor road designed for through traffic only,” reported a newspaper. “It by-passes a town. The central junctions are on the clover-leaf principle.”

The diorama also featured an “‘ideal’ Ministry of Transport trunk road, with cycle and pedestrian tracks.”

Cycle and pedestrian tracks were still being promoted in the federation’s New Roads for Britain report of 1944.

“Author, Mr. George C. Curnock, emphasises that roads and road planning should be the mainspring of all plans now being formulated for better social conditions after the war,” reported a newspaper, stating that “faster main road travel” would lead to “greater safety” for “motor traffic, cyclists and pedestrians.”

To “improve road transport conditions and reduce the appalling accident toll,” the federation urged the building of motorways and cycle tracks.

“Whenever possible the cyclist should be segregated both from other road traffic and from pedestrians,” the report said.

“There must be adequate cycle tracks between residential and industrial or recreational districts in all areas where the use of cycles is very considerable and along radial and arterial roads.”

CAR MANUFACTURERS

Car manufacturers tended to be libertarian when urging the state to build roads for motorists but dictatorial when discussing road use by those not in motor cars.

“Pedestrian crossings and cycle tracks have been introduced, but no effort is made to enforce their use,” complained J. P. Black, managing director of Coventry’s Standard Motor Company, in a letter about road traffic deaths to The Times in 1935. “Freedom will have to be restricted and a sense of responsibility shouldered,” he added.

Talking of cyclists on cycle tracks, the car manufacturer Lord Austin, in 1937, said:

“Cannot these nimble warriors be persuaded to … realise that traffic conditions have altered since 1900? Much has been said for and against the building of special tracks to accommodate the vast army of cyclists, but if road conditions have to be modernised on safe and progressive lines then the provision of special cycle tracks is inevitable, whatever fanatics may say to the contrary. In a few years’ time it will be [a] serious … offence for a cyclist to be on a motor road …”

COMPANY OF VETERAN MOTORISTS

Admiral G. H. Borrett of the Company of Veteran Motorists gave evidence to the Alness committee. CVM was founded in 1931 and had 34,000 members. It was renamed the Guild of Experienced Motorists in 1983, and now, as GEM Motoring Assist, provides breakdown services to motorists.

Lord Howe: “Has your association formed a view about the necessity for codifying the law relating to the highway?”

Borrett: “The law is rather hard on motorists, and the other road users have very little law to contend with at all … The whole law against motor-cars started in the old days when only the rich had cars … But nowadays, the whole population is interested in motor traffic … We think that a certain amount of propaganda could be usefully used in making ordinary people who do not own motor-cars realise how much they owe to motor traffic.”

Lord Howe: “What about cycle tracks?

Borrett: “Cycle tracks, of course, are most desirable … They should be wide enough, and when there are sufficient of them we think they should be made compulsory.”

COUNCILS

Many local authorities were keen on cycle tracks in the 1930s, sometimes out of genuine concern for road safety but more usually because the provision of such tracks was bundled by the MoT with the grant funding for dual carriageway roads.

Some councils — such as Buckinghamshire County Council — urged the Minister of Transport to introduce “legislation for an amendment of the law as to the use of roads by cyclists, which shall have the effect of compelling cyclists to use cycle tracks where these are provided.”

Others wanted cyclists to pay for cycle tracks.

Kent County Council “decided to ask the Association of County Councils to consider the desirability of pedal cycles being taxed,” reported a newspaper in 1936.

“They took this course in view of the heavy cost of cycle tracks which they have been advised by the Ministry of Transport to build alongside the new Ashford by-pass.”

“The cost will finally ruin the ratepayer,” claimed Thanet councillor E. S. Oak-Rhind.

“I was met with the knowledge that in all new schemes for new roads and in all schemes for widening roads the Ministry of Transport was insisting upon double cycle tracks being placed alongside footpaths. A very fine idea, but as they were to be concrete cycle tracks the cost must be enormous.”

Writing to newspapers around the country, Sir Edmund Crane, chairman of the Hercules Cycle company (then one of the largest bicycle companies in the UK), complained about the prospect of Dutch-style taxation of cyclists to pay for cycle tracks.

“Kent to-day, other places to-morrow. Let us make it plain and clear to county councils and to Parliament and the country generally that cyclists intend to exercise their rights of thoughtful and vigorous citizenship in opposing any idea of filching their liberty and of asking them to pay for filching.”

COUNTY SURVEYORS

Some county surveyors dismissed cycling infrastructure, but many others welcomed cycle tracks, possibly because they considered them interim measures.

In a 1935 report to the Warwickshire County Council’s roads committee, the county surveyor “visualised that, where dual carriageways were to be provided with possibly cycle tracks and service roads, an overall width of not less than 120 feet would be required.”

These cycle tracks “might be made and developed as service roads at a later date.”

The same assumption was made in a 1936 proposal by engineer R. D. Duncan, designer of what became Belfast’s Sydenham bypass (this was built in the 1950s — see “Post-War Tracks.”)

“In modern design, provision is usually made for the future widening of the carriageways by making broad verges,” wrote Duncan, adding that “part of which later may be use to obtain the extra width.”

MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT

Throughout this study, there are many examples of how, in the 1930s, the British government, via the Ministry of Transport, would only provide maximum road-building grants to local authorities if they included cycle tracks in their plans.

That this use of sweeteners was well understood to be institutional bribery by the MoT is clear from an exchange reported in a local newspaper in 1936.

Measham Lea of Worcestershire County Council’s Highways and Bridges Committee revealed that when local authorities around the UK submitted plans for roads 60 feet wide, the MoT usually rejected them, suggesting “additional width … for the provision of cycle tracks.”

“If,” he said, the council “went to the Ministry with a 100 ft scheme [with cycle tracks], they would get whole-hearted approval: the Ministry had actually offered to them an increased grant if they carried out a scheme on those lines.”

Mr Robinson, an official with the Ministry of Transport, gave evidence to the Alness committee.

“The number of cyclists is increasing and has increased considerably in recent years,” Robinson told the peers. “Unfortunately, cycle tracks are most needed in built-up areas where it is a physical impossibility to get the width without very large demolition of property.”

Turning to Major Cook, the MoT’s chief engineer, Lord Alness asked: “The cycle tracks of today, particularly the one on the Great West Road … are more or less useless, are they not?”

“They are used by 50 percent of cycle traffic,” replied Major Cook.

Lord Alness: “In Germany, cycle tracks are not only more numerous and wider but are always observed by cyclists.”

Major Cook: “Cyclists are compelled by law in Germany to use the tracks.

Lord Alness: “Have you contemplated the possibility of attaching a penalty to the non-use of cycle tracks of due width, when constructed?”

Major Cook: “…that requires legislation.”

Lord Alness: “Which would not be unopposed I presume?”

Major Cook: “Which would not be unopposed.”

NEWSPAPER COLUMNISTS

Newspaper editorials — often penned by motoring correspondents — thundered their support for cycle tracks throughout the 1930s.

Accompanying a news story about the opening of the first cycle track in London in December 1934, the Western Daily Press opined that “separate tracks for cyclists … are amongst the possibilities of the future which cannot be ignored.”

Admitting that cyclists were a “numerous contingent” (they were, in fact, the majority users of roads in this period) and were “entitled to protest” against cycle tracks, the newspaper soothed that “as a body, cyclists have nothing to gain by closing their eyes to the tremendous changes that have taken place on the roads during recent years and which make further rationalisation unavoidable.”

The editorial imagined that “it is hard to see what there is against [cycle tracks],” stating that “mere windy assertions about the inviolable rights of true-born Britons to go as they please lead nowhere.”

“Provided the tracks for cyclists — which taxpayers, after all, are not exactly longing to construct — are well made and entail no inconvenience, the cyclists can have no reasonable objection, and should feel gratitude,” editorialised the Dundee Evening Telegraph in 1936.

“Motorists would not object if special motor roads were made,” continued the editorial.

“In certain foreign countries, pedestrians, cyclists and motorists are segregated on the newer roads, and no one suggests that the arrangement is not in every way commendable.”

PEERS

The Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents — or just the Alness Committee — was chaired by Lord Alness and it heard from expert witnesses in 1938 and 1939.

In evidence given to the committee, witness after witness — from surveyors to arch motorists — attested to the dire nature of England’s experimental cycle tracks, but, apart from cyclist witnesses, most wanted cyclists to be forced to use the tracks.

There were 231 recommendations in the resulting Alness Report, including that children of ten and under should be banned from the public highway on bicycles and that road segregation should be carried out with utmost urgency. According to the report, cyclists should get high-quality cycle tracks and be forced to use them. Pedestrians were also to be fined for daring to cross the road at points other than designated crossing points. Motorists, decided the (motoring) Lords, should be treated with a light touch by the law, and be provided with motorways and many more trunk roads. (There were no recommendations that motorists should be restricted to the proposed new motorways alone.)

Roads were mostly for motorists, decided the Lords. In a section headlined “Alternative routes for cyclists,” the Alness Report suggested that “road authorities should indicate alternative routes which are available for cyclists, and so take them off the main streets. Local cyclists probably know these routes, but cyclists who are strangers to the locality would be helped by being able to find these alternative routes, which, though more or less parallel with the main thoroughfares, would be in quieter streets.”

Here, in full, is the section dealing with cycle tracks:

The Committee regret to say that they regard the attitude of the majority of the representatives of cyclists’ clubs towards cycle tracks as unreasonable. Their point of view seems to be that cyclists should not be excluded from the King’s Highway, and that, if they were relegated to cycle tracks, it would not only abridge their rights, but would make cycling less enjoyable. They appear to pay little or no attention either to the risk they themselves run, or to the danger to which they expose other road users. In spite, however, of the intransigeant point of view adopted by some of their leaders, a census shows that the great majority of cyclists use the tracks provided for them.

There are, however, only 45 miles of cycle tracks in existence, and 68 miles under construction, out of a total of 180,000 miles of road in Great Britain. The Committee consider that, wherever possible, cycle tracks should be constructed, particularly on arterial roads which are intended for fast motor traffic. They should be of adequate width, 9 or even 12 feet broad, and of good surface.

In large towns the volume of cycle traffic often becomes automatically “one-way traffic”, as in the morning people go to work at factories outside those towns, and in the evening they return home. In such cases it may be safer for cyclists to use one broad cycle track in both directions rather than to be obliged to cross the road in great numbers. Normally, however, there should, where feasible, be a cycle track on both sides of the carriageway. Their use should be made obligatory where they are satisfactory, except, of course, when the cyclist is turning to cross the road.

Failure to use them should be made an offence. In Belgium and in Holland cycle tracks are marked in certain cases “Obligatory”, and in other cases “Not obligatory”. This practice might well be followed in Great Britain. Cycle tracks are still in an experimental stage, and the existing tracks stand in need of improvement. Particular attention must be paid to cross roads, for 75 per cent of the accidents in which cycles are involved occur there. It is essential that where entrances to carriage drives, houses, etc., cross a cycle track at a lower level, the level of the track surface should prevail.

There are many rights of way, bridle paths and disused roads, such as parts of the Fosse Way, throughout the country. In many cases they are short cuts from one village or town to another. The Committee consider that, where feasible, these might be turned into cycle tracks. This would increase the pleasure of cycling, and would reduce the volume of traffic on the main roads.

The Committee are also of the opinion that, when roads are widened, it would improve the amenities — an effect which has already been achieved in some instances — if existing hedges were allowed to remain, and cycle tracks and footpaths were put on the other side of the hedge. The segregation of carriageways would thus be increased. Cycle tracks might also be taken behind petrol stations where possible. The owners of the latter would in all probability agree to this proposal.

When questioning witnesses, the peers on the committee — the Lords Iddesleigh, Birkenhead, Brocket, Rushcliffe, Addison, and Alness — had frequently mentioned their love of motoring, a bias not lost on interested parties. In a parliamentary debate welcoming the Alness report, Lord Sandhurst said:

… the editor of Cycling finds it necessary to invent a new body of your Lordships’ House, which he calls the Peers Road Council. Having invented it, he then elects four members of the Select Committee to it — the noble Lords, Lord Reading, Lord Iddesleigh, Lord Birkenhead, and Lord Brocket — and then, having described them as keen motorists, he says, “Let us see what this Committee recommends for cyclists.” What is the idea? Obviously they are trying to get at their not too well educated public and suggest that this is such a biased Committee that no attention need be paid to their recommendations.

The motoring bias of the report is as apparent today as it was then. Motoring organisations and magazines were very much in favour of almost all of the report’s 231 recommendations. Commercial Motor described the report as “the finest of its sort that has ever appeared” and applauded its victim-blaming approach:

The case for the fair-minded motor driver has been put forward admirably. There is little need to read between the lines to appreciate that the Committee is fully aware how the good driver is constantly “nursing” the careless pedestrian and, often, the cyclist … Exception is taken to “a popular fallacy … that the motor driver, being in control of what is sometimes termed a lethal weapon, is usually to blame when an accident occurs.” This is a destructive attitude, whilst the Report throughout is constructive. Its compilers obviously realize that progress, represented by fast road transport, is desirable, that the change of conditions following in its train must be accepted, that the mode of life of the people must be modified in accordance and adapted to the new conditions, and not that progress should be checked in order that that mode of life may remain unaltered.

There was palpable excitement from the peers at the prospect of German-style autobahns being built in Britain — free of cyclists, pedestrians, and animals — and frustration when cyclist and pedestrian groups said they recommended that motorists who went fast on motor-specific roads should be restrained on ordinary roads.

At the time, cycling was booming. Six million more people had taken to riding bicycles since 1928, the peers were told — a fact that “staggered” Lord Alness. Cyclists were primarily “proletarian,” said one Lord in the debate launching the Alness report in 1939, and so were not deemed to be as valuable to the economy — or the war effort — as motorists. (In the 1930s, the motor industry was cosseted because it was expected that car production would be shifted to military vehicle production; bicycle factories, such as the Raleigh plant, were also converted for armaments production but Sturmey—Archer gears couldn’t power tanks. And roads, unlike the railways in the 1926 General Strike, couldn’t be brought to a standstill by powerful unions.)

“Cyclists seem to me to be the chartered libertines of the road. They are not subject to any restraint at all. They are not taxed, they are not registered, they are not numbered and they are not obliged to insure, they are not even obliged to ride on the tracks which are specially provided for them, and they are not obliged to report accidents. They are not even obliged to carry bells or brakes. They are at complete liberty to do what they like. All that must come to an end.”

Lord newton

One of the witnesses to the Alness Committee showed how motorists, then a powerful minority, had no qualms over extinguishing the rights of a majority: “[Cyclists] ought to be forced to use [tracks]. The only reason they escape is because there are so many of them. There is a vague idea on the part of Governments that they would lose the cyclists’ vote.”

This was the claim of Lord Newton, who repeated the claim when the report was published: “[cyclists] form a very formidable body, of which all Party politicians are very much afraid. That is the sole reason why they have not been regulated up to now, and I hope sincerely that that state of things will come to an end.”

Cyclists, Lord Newton told his fellow peers, “seem to me to be the chartered libertines of the road. They are not subject to any restraint at all. They are not taxed, they are not registered, they are not numbered and they are not obliged to insure, they are not even obliged to ride on the tracks which are specially provided for them, and they are not obliged to report accidents. They are not even obliged to carry bells or brakes. They are at complete liberty to do what they like. All that must come to an end.”

In evidence given to the Alness committee, CTC officials had stressed that the main objection was to the quality of cycle paths and not just the principle of being able to continue riding on the carriageway, the hard-won right of cyclists since 1888. The CTC feared that legislation would be brought in that would make it compulsory to use cycle paths even before a useable network had been built and that, going by the poor provision of paths in the previous five years, there was little likelihood that the paths of the future would be of decent quality.

The following exchange between the peers and CTC secretary George Herbert Stancer clearly shows the antagonism between the parties, although the CTC man remained polite throughout.

Lord Alness: Your Association is, if I may say so, broad-minded enough to regard motor traffic as necessary and proper development?

Stancer: Yes, my Lord. Of course we have grown up with the motor movement and I think that during the whole of that period we have treated it with perhaps more tolerance than we have always received at the hands of the people who have been concerned with motoring.

Lord Alness: Is your Club in favour of the construction of motorways?

Stancer: Yes, my Lord, we have been advocating that for many years.

Lord Alness: Is your Club in favour of the provision of separate cycle tracks for cyclists?

Stancer: No, my Lord, we are not. Our feeling is that cycle paths at the side of the road do not, in the present circumstances, and never can, provide the same facilities for enjoyable cycling as are provided by our present road system.

Lord Alness: I should have thought personally that it would be more enjoyable to cycle on the cycle track on the Great West Road than to cycle on the highway there?

Stancer: Those people who are not accustomed to cycling always tell me that and I think that it must be a general view … The fact of it is that the existing experiments in the construction of cycle paths are, I think, most unsatisfactory and they have created a bad impression amongst cyclists.

Lord Alness: Assume the track was adequate in dimensions, in breadth, as in Germany, 9ft let us say, and its surface was good, do you not approve of the experiment at least being made?

Stancer: The difficulty is not so much a matter of width or surface. It would be essential to provide a sufficiently wide track and most of the tracks we have knowledge at present are too narrow and the surface is very unsatisfactory. On most of them even if we had a sufficient width and an excellent surface there is still the disadvantage that the track by the side of the road is constantly being interrupted and broken by the passage of other tracks coming from houses or whatever it may be. Every time there is a private house with a garage or there is a filling station or there is a way into a field or way into a shop … everything has to come across the cycle path; so that while on the carriageway you get a perfectly straight, smooth, unbroken, uninterrupted course for whatever vehicle is using it, the cyclist has always got something coming across.

Lord Alness: But he is not submitted to the same dangers as when he is cycling on the highway on the Great West Road?

Stancer: No, my Lord. My suggestion is that those dangers ought to be removed.

Lord Alness: Is that not a counsel of perfection? The removal of the dangers seems rather idealistic?

Stancer: The other alternative seems to be a counsel of despair: “The law is powerless to preserve you on the road now; you must get off the road.” That is roughly what it comes to.

The six Lords were disappointed with the answers from Stancer so recalled him five days after his first appearance. Showing how far the erosion of non-motorists’ rights had gone, Lord Brocket asked, in all seriousness: “Then you consider that cyclists and motorists have an equal right to the road?”

Stancer: Yes.

Lord Brocket: But you realise that motorists pay for the upkeep of the roads to a certain extent?

Stancer: I realise that they frequently say so but in point of fact the main costs of the roads is borne by the ratepayers, and the ratepayers include cyclists. I know to my cost that I pay an enormously large sum in rates for the use of roads which have been rendered much more costly by the requirements of motorists. Pedestrians and cyclists … are paying excessively for the provision of roads which are mainly intended for the use of motorists … It is unfair to say motorists pay for roads.

Earl of Iddesleigh: If we could enable you to avoid the great motor roads and provide for you really satisfactory roads on which you would not have to compete with a great deal of fast moving traffic, there would be a gain in enjoyment?

Stancer: If it were possible to provide facilities that are equal to those that we enjoy now, with the additional advantage that they would not be shared by motorists, I think that cyclists would have no objection …

Earl of Iddesleigh: Are the two grounds upon which you are against cycle tracks these? First, because the cyclist insists on his abstract right to the use of the highway, and secondly, because it is less pleasant to use a cycle track than a highway?

Stancer: The second one you have mentioned is far more important. Cyclists would never insist upon their abstract rights if it were not that they are losing the chief pleasure of cycling by being forced on to the paths. If the paths are by any miracle to be made of such width and quality as to be equal to our present road system, it would not be necessary to pass any laws to compel cyclists to use them; the cyclists would use them.

The House of Lords committee published its findings in March 1939; in September war was declared and the construction of a national network of cycle tracks ground to a halt. The Alness report — derided by Labour MP William Leach as a “tale of deaths and manglings … and extraordinary conclusions” — was mothballed. After the war, a House of Commons select committee dusted it down. Many of the recommendations in the Alness Report were taken forward, especially the pro-motoring bits, but, for a while at least, there would be no motorways and few new cycle tracks.

POLICE

Sir Herbert Alker Tripp, assistant commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police, gave evidence to the Alness Committee on behalf of all police forces.

“To safeguard [pedestrians], we should have our footways at first floor level in every street and with bridges between them,” Tripp told the peers.

“That would eliminate the pedestrian casualties entirely. In the same way with the pedal cyclists we should want separate tracks. If we had in London a layout designed for motor traffic only we could reduce the pedal cyclists casualties probably by 50 or 75 percent…”

Lord Alness: “Have you any suggestion to make with regard to any improvement to sanction with regard to conduct [of the motorist]?

Tripp: “I have none. He has been the subject of regulation … over this period of years, and I do not think things can be carried very much further … Accidents are caused by encounters between the motorist on the one hand and the pedal cyclists on the other. We have at present a system of unilateral restriction on the driver, and the effect of unilateral restriction is inclined to cause the unrestricted party to be bolder and more arrogant, and I would not at the present moment advocate any further regulation with regard to the motor driver.”

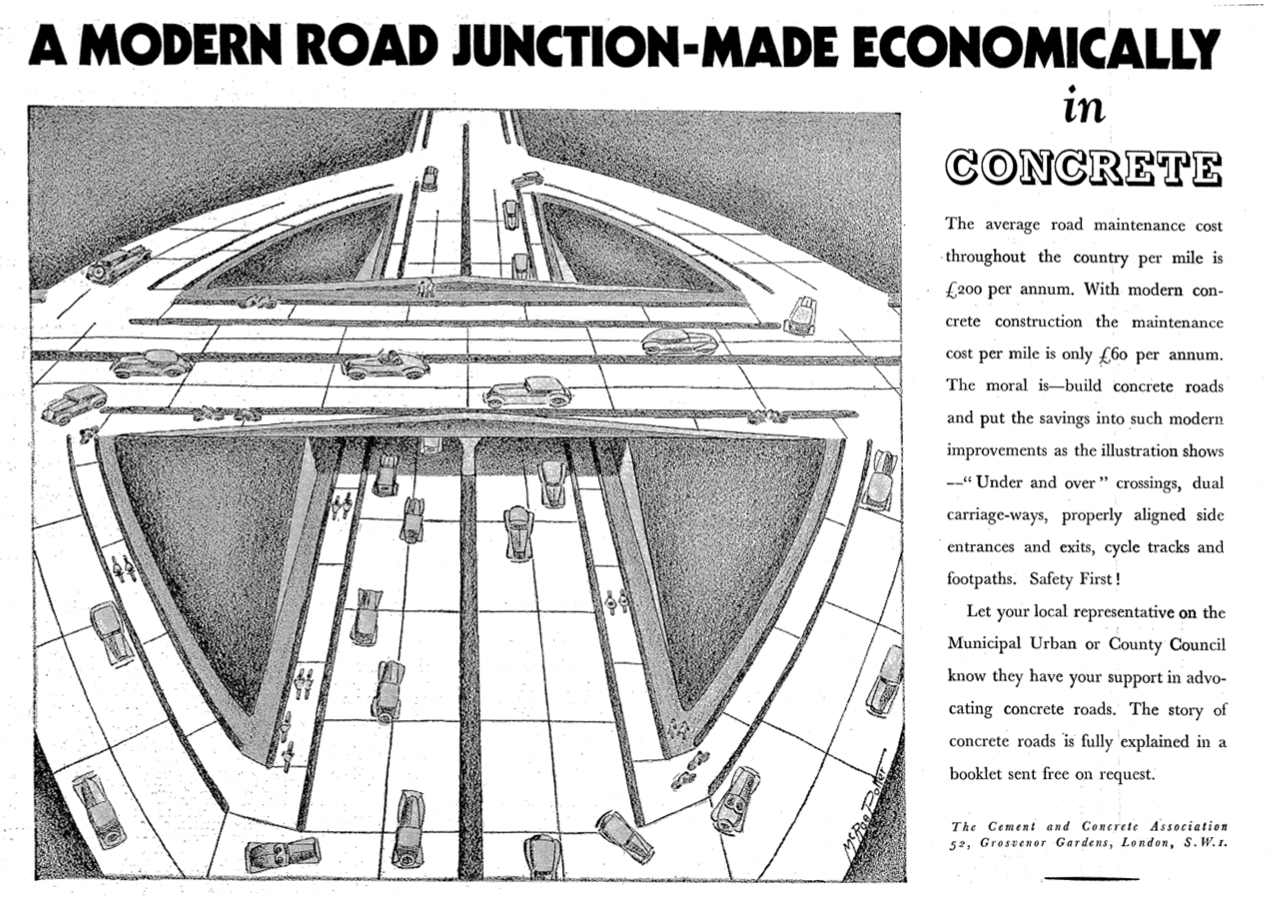

ROAD BUILDERS/PROMOTORS

Sniffing the wind, road builders were in favour of cycle tracks. Just so long as their clients were also in favour. Tarmac promoted “Grittite” as a period cycle track surfacing material. And the Cement and Concrete Association published pamphlets on the ideal material to be used for roads and cycle tracks. Concrete, it just so happens.

ROAD HAULAGE ASSOCIATION

Today’s Road Haulage Association was formed in 1945 from the merger of the Commercial Motor Users’ Association and Associated Road Operators.

In a 1937 speech delivered in Sheffield, Robert Barr, vice-chairman of the Commercial Motor Users’ Association, said there should be “dual carriageways on all main roads” and that “cycle tracks and footpaths be provided on all classified roads within five miles of towns.”

He also wanted “pavements to be raised to first floor, thus leaving greater width for streets,” and “bridges for pedestrians or subways under raised roads.”

Also in 1937, J.F E. Pye, chairman of the Metropolitan area of Associated Road Operators, addressing an AGM, said that “cycle tracks were no use until a law was passed making it compulsory for cyclists to use them.”

The Western Daily Press added: “Mr. Pye reported to have made one observation which, of course, for a man in his position, was indiscreet, to say the least. He is alleged to have said that ‘a cyclist never more valuable than when a lorry driver knocks him down.’“

ROADS BEAUTIFYING ASSOCIATION

“The Roads Beautifying Association … has just issued, in conjunction with the Automobile Association, a booklet showing by word, diagram, and photograph, how improvement of the highways can make a tremendous contribution towards the reduction of road accidents,” reported a Scottish newspaper’s motoring correspondent in 1937.

Under the subheading “Cycle paths,” the correspondent wrote: “[The Highway Beautiful] not only asks for dual carriageways, accident-proof crossings of the clover-leaf type, and cycle and pedestrian paths, but shows how they could be provided without interfering with the beauties of the countryside.”

“In Holland,” continued the correspondent, “the cycle tracks conform to the general direction of the main roads, but, winding and informal, they are usually hidden behind high hedges and retain their rural charm. It is interesting to find the Roads Beautifying Association recommending the construction of similar tracks here, but they will be of little value unless the cyclists are compelled to use them.”

The Roads Beautifying Association was founded in 1928 by Lord Mount Temple, the then Minister of Transport, to provide an organisation through which the voluntary services of horticultural experts were made available to local authorities to advise them in the planting of highways.

ROADS IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION

Early in the 20th Century, the Roads Improvement Association (RIA) had become a lobby group for motorists, but it was founded in October 1886 by the National Cyclists’ Union and the Cyclists’ Touring Club.

In the 1930s, the lobbying group — still with cycling organisations as members — pushed for cycle tracks.

“Roads in busy central areas should have twin carriageways with cycle tracks and footpaths each side,” wrote RIA general Wallace E. Riche in October 1936.

“All arterial roads should be capable of accommodating four lines of traffic, one fast and one slow in each direction –and of providing some additional space for cyclists and for manoeuvring when vehicles are stationary from any reason.”

The long-time secretary of the Roads Improvement Association was arch-motorist William Rees Jeffreys. He, too, was mightily interested in the construction of period cycle tracks. In his 1949 memoir The Kings Highway he wrote that cycle tracks were part of a “progressive adaptation of new roads to traffic needs.”

He had skin in the game — he had been an avid long-distance cycle tourist in his youth and, in the late 1890s, became an official with the Cyclists’ Touring Club.

Jeffreys was one of the key promoters for the improvement of Britain’s road network, work he started as a cyclist.

“The conception of the construction of wide, new roads in this country is due to Mr. W. Rees Jeffreys …” said the City Engineer of Liverpool in 1925.

Rees Jeffreys took over the running of the Roads Improvement Association in 1900 while a council member of the Cyclists’ Touring Club. His first experience of the new science of road crust manufacturing came while he was employed by the CTC. He would run the Roads Improvement Association until the 1950s.

ROYAL AUTOMOBILE CLUB

“[The RAC seeks] the provision of cycle tracks,” club solicitor Corris William Evans told the peers on the Alness committee.

“That, we feel, has not been carried out to the extent it might have been. Six feet [for cycle tracks] is probably insufficient on a heavily cycle trafficked road. [Compulsion should be enforced when the track is of] appropriate width and appropriate surface … [In rural areas] where footpaths are provided, and cycle tracks are provided and a roadway is provided, we have found that the pedestrian, owing to the condition of the surface of the path, will walk on the cycle track and the cyclists will proceed along the carriageway.”

According to The Times Evans said: “[The] Club was of the opinion that certain legal obligations of a character which it would be no hardship on the cyclist to observe should be made, [including] the provision of cycle tracks.”

Meanwhile, seemingly without a shred of irony and similar to the view espoused by Sir Herbert Alker Tripp of the London Metropolitan Police, he added that “the Club considered that restrictions on motorists were sufficient, and that the penalties provided for motoring offenders were adequate …”

TRANSPORT ADVISORY COUNCIL

The Transport Advisory Council (TAC) was an expert body founded in 1934 and known at the time as the “Traffic Parliament,” and charged with exploring how to reduce road deaths. The body consisted of representatives of local authorities, motoring organisations, industry associations, water-borne traffic and docks, railway interests, equestrians, cyclists, and pedestrians.

TAC’s “accidents to cyclists” sub-committee consisted of thirteen members, including five Sirs, three Justices of the Peace, but only one cyclist, Frank Urry of the Cyclists’ Touring Club.

In 1936, Parliament commissioned TAC to find out why so many cyclists were killed on Britain’s roads and what could be done about it. Several members went on fact-finding trips to Denmark, Germany, and Holland “where the proportion of cyclists is high,” reported The Scotsman.

TAC reported its findings two years later, and its report was accepted by the then Minister of Transport, Leslie Burgin. “The Transport Advisory Council … have now reported and made a number of recommendations,” Burgin told Parliament in June 1938.

“Perhaps the most important of these are the building of cycle tracks of a particular type, and, where such tracks are built and are satisfactory, the making of the use of them compulsory,” said Burgin.

The transport minister did not mention that there was a dissenting voice on TAC’s report.

Urry wrote: “I cannot subscribe to the recommendation of extending the building of cycle tracks, or the compulsory use of them by cyclists if and when laid down. The danger of right-hand crossings discounts any presupposed safety obtained by partial traffic segregation; and it has been admitted that where cycle tracks are in being, motoring speeds on the carriageway will increase, to the consequent danger of the cyclists when the cycle track ceases, as it must do on over 95 percent of our highways. Cycle tracks are a palliative at best, and in my opinion a dangerous one.”

It’s worthwhile quoting TAC’s report at length.

“Our terms of reference were to consider and report upon any further practicable measures which might be adopted for the better protection of cyclists and other road users. Our attention was drawn to the large and continued increase in the number of pedal cycles in use upon the roads and to the large number of accidents in which pedal cyclists are involved,” started the committee’s report.

“In view of the large number of persons who would be affected by any of the Council’s recommendations upon which the Minister may decide to take action (the number of cyclists in Gt Britain is variously estimated at from 8 to 10 millions) we felt it to be essential, not only that we should obtain the views of all sections of the community affected but also that we should ourselves personally make outdoor observations.

“We also carried out an inspection of the cycle tracks on St. Helier Avenue, Sutton By-Pass and on Western Avenue.

“In addition, in order to study conditions in countries where the cycling problem is at least as acute as in Great Britain five members, the Chairman, Mr. Gaunt, Mr. Hughes, Sir John McDonald and Mr. Urry paid a visit to Denmark, Germany, Holland and Belgium. We consider this visit to have been of considerable assistance to us in our deliberations.”

The committee concluded that cycle tracks should be built and, further, that use of the tracks by cyclists should be compulsory.

“Of the organisations from whom we received evidence, practically all, with the exception of the cyclists’ representatives, were in favour of the extended provision of cycle tracks,” stated the committee’s report.

“On behalf of the cyclists, objections to this proposal have been made on the grounds that it was thought to be a preliminary to driving cyclists off the road altogether, but we are convinced that such a step could never be seriously contemplated. We are aware, moreover, that the cyclists’ organisations advocate the construction of highways specially reserved for motor traffic. We cannot see where the principle involved herein is different from that of providing separate tracks for cyclists within the limits of the highway.

“We are, ourselves, satisfied of the importance, from the point of view of reducing accidents, of providing separate tracks for classes of vehicles whose speeds differ considerably, more particularly as the classes of road user so segregated differ also in their relative vulnerability. We fail to appreciate the objections raised by cyclists to the provision of cycle tracks.

“Pedestrians do not object to the increasing provision of footpaths.”

“We appreciate that on some roads in this country cycle tracks constructed after the main carriageway are not such as to encourage the cyclist to use them, being crossed at frequent intervals by garage accesses and, in some cases, being used also by pedestrians. We are agreed that the tracks should be reserved for cyclists and that their surface should not be inferior to that of the main carriageway.

“We accordingly make the following recommendation … that cycle tracks and footpaths should be provided on both sides of new main roads … [and that] cycle tracks should be used by cyclists only.”

“The question whether, where cycle tracks are provided, their use should be made compulsory has resulted in lengthy discussions,” admitted the committee’s report.

“It has been pointed out that, in certain localities, for instance, in the neighbourhood of factories where large numbers of workers travel by cycle between their home and their work, there are certain times of day when, if the use of cycle tracks were made compulsory, it would be physically impracticable to accommodate the whole of the cycling traffic on cycle tracks unless the tracks were widened to an unreasonable extent. It has also been represented that, if the use of cycle tracks were made compulsory, point would be given to the cyclists’ objection noted above, that the construction of cycle tracks was but a preliminary to prohibiting cyclists from main roads altogether. In spite of the suggestion put forward that in the course of time, cyclists will come to use the tracks automatically to the extent that they are used in Continental countries, we feel that this time may be far distant and that, until it has come, the value of cycle tracks would be very greatly lessened if their use were not made compulsory. We appreciate, however, the difficulty that tracks near factories may be unable to cope with the volume of cycle traffic which exist in those localities at the rush hours. We recommend therefore, that where cycle tracks are provided, their use should be made compulsory by means of suitable signs, with the proviso that power should be given to the police or to the highway authority to suspend the operation of this requirement in specified localities and at specified times. This should be done by an amending notice on the signs.”

The committee — except for its dissenting member — might not have considered its stipulation that use of cycle tracks should be made compulsory was, in effect, a measure to restrict cycle use but period newspapers reported this would be the result.

In a news story on the TAC report the Daily Herald’s headline was stark: “Drastic move to curb road users.” The standfirst stated the “revolutionary” plans “would limit the freedom of cyclists.”

Many wanted such freedoms to end. Under the headline “Discipline for cyclists” the Hull Daily Mail in 1938 said:

“Traffic experts want cyclists disciplined … English cyclists enjoy more freedom than in any other country, and now that cycle tracks have been provided it is only a common sense demand that they should be used.”

Despite the effort in compiling TAC’s report, its main recommendations were put on hold until the March 1939 publication of the report on general road safety produced by the Alness Committee.

TRANSPORT MINISTERS

In a February 1934 parliamentary question aimed at the transport minister (today, this would be the Secretary of State for Transport) Tory MP for Penistone Clifford Glossop urged for the “placing of special cycling tracks at the side of main roads, as in Continental countries, particularly Holland.”

“Only the other day I cycled to this House on a pedal cycle,” he added and stressed that cyclists “ought to be assured of a reasonably safe place to cycle in.”

“At present,” Glossop continued, “the wretched cyclist is always being frightened by the hoot of an electric horn and is very often forced into the ditch or into the kerbstone.”

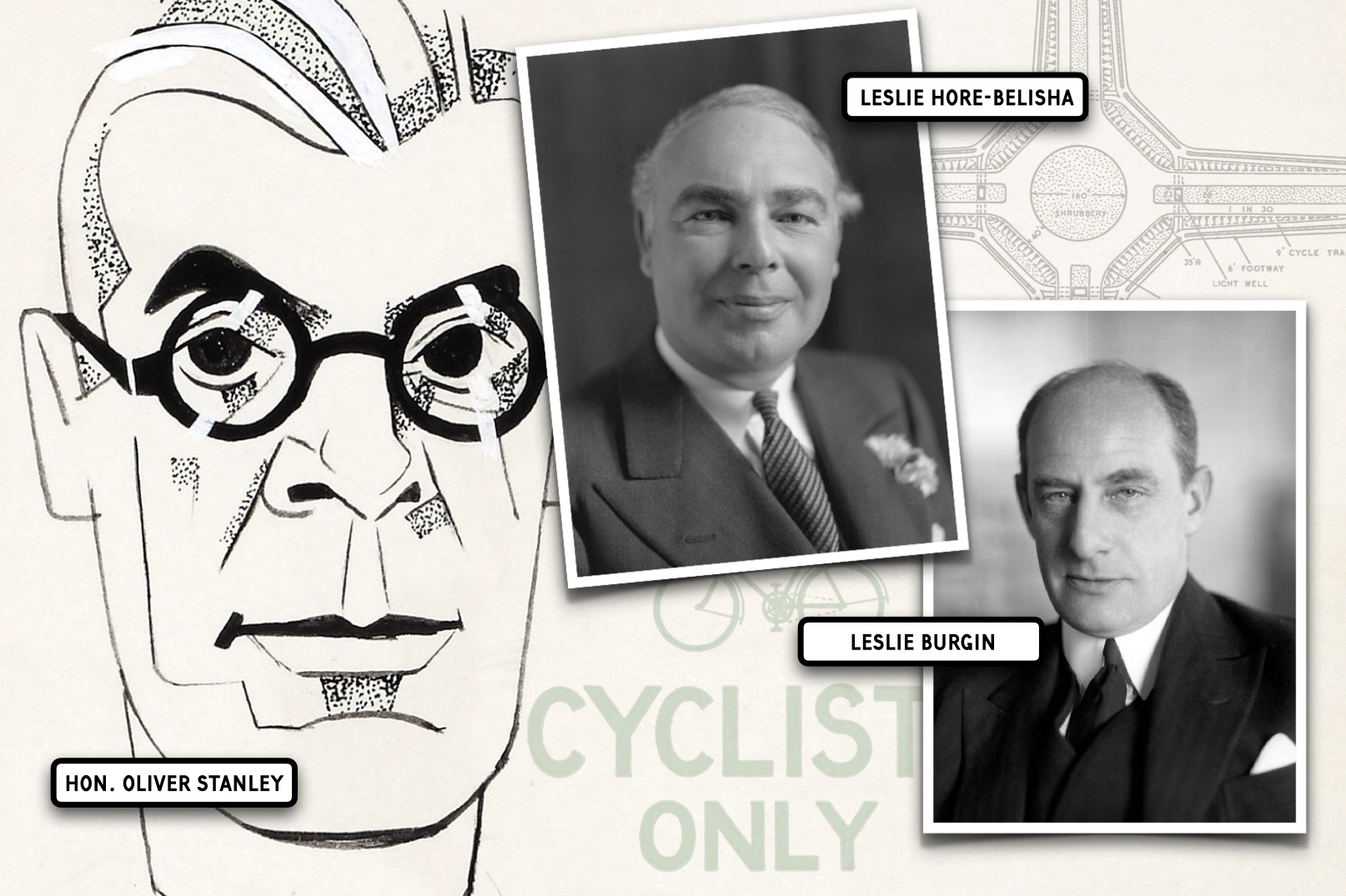

Replying, transport minister Oliver Stanley said he was minded to commission an experimental cycle track but that, to date, cycling organisations had been opposed to such infrastructure.

“Whenever cycling tracks have been suggested it has always been the association representing ‘the wretched cyclist’ which has protested most bitterly against them, and for reasons which are not unsubstantial,” said Stanley. “But I am considering whether it might not be advisable to provide, for the experimental use of cyclists themselves, to let them see how they like it, a cycling track along one of the roads near London, not with the intention of forcing them to use it, but with the possibility that if they become familiar with its use their opinion of its utility may be changed.”

Thereafter Stanley set in motion the 1930s cycle track programme. According to a March 1934 newspaper report, he “circularised local highway authorities throughout the country asking them to suggest suitable places for the introduction of ‘cycling tracks’ and ‘motoring lanes’ on some of the larger main roads, and thus lessen the risk of road accidents.”

| Hon. Oliver Stanley | 1933-1934 | Conservative |

| Leslie Hore-Belisha | 1934-1937 | Liberal then Conservative |

| Edward Leslie Burgin | 1937-1939 | Liberal |

| Captain Euan Wallace | 1939-1940 | Conservative |

| Lieut-Colonel John Moore-Brabazon | 1940-1941 | Conservative |

| Alfred Barnes | 1945-1951 | Labour |

| Alan Lennox-Boyd | 1952-1955 | Conservative |

| Ernest Marples | 1959-1964 | Conservative |

| Thomas Fraser | 1964-1965 | Labour |

At the end of June 1934, Stanley became the Minister for Labour and it was his successor as transport minister, Leslie Hore-Belisha, who, later that year, cut the ribbon on the first cycle track on Western Avenue, Ealing.

(Hore-Belisha did not start the cycle track programme, nor did he start the programme of “zebra” pedestrian crossings to which part of this surname later became attached. “Stanley beacons” wouldn’t have had the same alliterative appeal as “Belisha beacons.”)

Like Stanley before him, Hore-Belisha argued the provision of cycle tracks was not to rid the roads of cyclists but to provide a safe haven for those on bicycles.

“Are not casualty lists and the number of accidents involving cyclists, themselves arguments for the provision of experimental tracks of this kind?” asked Hore-Belisha at the ribbon cutting on 14th December.

“Of the 7,202 persons who died as the result of road accidents last year 1,324 were pedal cyclists. Out of the 184,781 non-fatal accidents, pedal cyclists were involved in 43,789. A distressing feature of these figures is that they disclose that about half of those who were killed were under the age of 21. The evidence before me shows that accidents to cyclists are increasing.”

According to a report on the ribbon-cutting ceremony in the Manchester Guardian, “the provision of the two cycling tracks would give effect … to the principle that classes of traffic should be segregated in accordance with the speed at which they could move.”

In a speech later the same day, at a luncheon at the Empire Stadium, Hore-Belisha complained that cycling organisation “have made up their minds in advance that these cycling tracks are an assault on their privileges and deprive them of their rightful use of the highway.”

This was not true, he claimed. “Nothing has been taken away from [cyclists], but something has been given.”

He continued: “I do not see why it should be considered less reasonable to provide cyclists with a cycling track than a pedestrian with a pavement. I have never heard that a pavement is a deprivation for pedestrian of the use of the King’s highway.”

An editorial in the Manchester Guardian agreed: “To provide tracks for cyclists is no more an infringement of their liberty than to provide pavements for pedestrians and if in the future it is decided to divide the road still further into lanes for slow and fast moving traffic there will surely be no complaint from the lorry-drivers that they are being driven off the road.”

(No such tracks for trucks were ever provided, and had they been, it is almost sure that lorry drivers, and their representative organisations, would have opposed their introduction.)

At a 1936 meeting of the Commercial Motor-users’ Association, which later morphed into the Road Haulage Association and was an organisation not known for its interests in cyclist safety, Hore-Belisha pledged the “provision of nearly 500 miles of cycle tracks,” a statement which was “greeted with applause,” reported a newspaper.

“We at the Ministry will try to provide for, and anticipate, the transport industry’s demands upon the roads,” he told those gathered at the luncheon.

“I can promise you that we will proceed with vigour and determination to give you what you require,” he added.

Under Hore-Belisha’s direction, the MoT proposed certain design standards for new roads. “For an 80-foot road there should be dual carriage-ways and footpaths; for a 100-foot road, dual carriage-ways with footpaths and cycle tracks; and for 120-foot roads and upwards, dual carriage-ways each exceeding two traffic lines, with footpaths and cycle tracks,” reported the Birmingham Daily Gazette in July 1936.

In a speech, Hore-Belisha said the provision of cycle tracks and hundreds of miles of new roads “shows the efforts we are making to meet the demands which an increasingly prosperous motor industry and a more mobile population are making upon us.”

Design standards were formalised in a MoT memorandum, prepared in consultation with representatives of the Institution of Municipal and County Engineers and the County Surveyors Society, and sent to local authorities in 1937.

This “code for road-builders” said new roads should be “equipped with dual carriageways, cycle tracks, and in suitable cases grass tracks for horses.”

In Parliament, Hore-Belisha admitted that the provision of cycle tracks wasn’t just to save cyclists’ lives but also to reduce congestion.

In a 1936 debate, an MP asked Hore-Belisha about the width of the Great Western Road in London. The transport minister replied that “I am glad to say that they intend to put down cycle tracks there so as to relieve the congestion.”

Edward Burgin succeeded Hore-Belisha as transport minister. He was also supportive of cycle tracks, and, like his predecessors, he also cited cyclist safety as the main reason for cycle tracks.

“Every user of the road knows something about the problem of the cyclist, a body of road users on whom the toll of accidents falls heavily,” he explained to Parliament in 1938.

Citing the findings of the Transport Advisory Council’s report on cyclist safety from 1936, he said: “Perhaps the most important of these [findings] are the building of cycle tracks of a particular type, and, where such tracks are built and are satisfactory, the making of the use of them compulsory …”

He added that “so far as possible each class of traffic should be segregated, not only according to the direction in which it is travelling, but in accordance with its character and its speed. Dual carriageways, separate footpaths, separate cycle tracks, and adequate margins are generally desirable, though, of course, the physical conditions of each locality have to be taken into account in deciding how far that ideal is practicable.”

Lieut-Colonel J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon was vice-chair of the Automobile Club, a motorist, and a racing car driver since 1903. He was also the minister of transport between 1940 and 1941.

As the representative of Middlesex County Automobile Club he gave evidence to the Alness committee.

Lord Alness: “Are you in favour of cycle tracks?”

Moore-Brabazon: “Yes, but I think you have to give them very good cycle tracks, you know. They are given very bad cycle tracks which make them jump all over the place.”

Lord Alness: “You would hardly blame a cyclist for failing to utilise the 6ft-wide cycle track on the Great North Road?”

Moore-Brabazon: “No.”

Lord Alness: “Should use of these tracks be compulsory?”

Moore-Brabazon: “Yes, providing the track is a good one, I think it should be compulsory…I think what you have to do is to make the tracks so attractive as to attract the people automatically; then you could put the penalty on; but to force them on to something which is not good is very difficult.”

These were conciliatory views from Moore-Brabazon. Earlier, when a backbench MP, he told Parliament in 1934 that everything and everybody should get out of the way of motorists:

“It is true that 7000 people are killed in motor accidents, but it is not always going on like that. People are getting used to the new conditions… No doubt many of the old Members of the House will recollect the number of chickens we killed in the old days. We used to come back with the radiator stuffed with feathers. It was the same with dogs. Dogs get out of the way of motor cars nowadays and you never kill one. There is education even in the lower animals. These things will right themselves.”

Arterial roads, he asserted, “were built with motorists’ money in order to allow motorists to speed up …”

NOTES

[1] Report by the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents (session 1938-39). https://archive.org/details/b32170312

[2] The BRF’s website ceased updating in 2001. https://web.archive.org/web/20000520004819/http://www.brf.co.uk/

[3] Members in 1933 included British Road Plant Manufacturers Association, Commercial Motor Users Association, Furniture, Warehousemen and Removers Association, Motor Hirers and Coach Services Association, Omnibus Owners Association, Petroleum Distributors Committee, Road Haulage Association, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders. The BRF had offices at 186, Palace Chambers, London, S.W.1,

[4] Dundee Courier, 08 September 1937.

[5] The Scotsman, 02 September 1937.

[6] It’s likely that this model was made for the British Roads Federation by the long-established Thorp Modelmakers, a firm still in existence. Thorp made other post-WWII highways dioramas for the Federation. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/browse/r/h/86ff1bc9-e2b9-4cb7-836c-e42f1c0b5803 See also A History of Architectural Modelmaking in Britain

The Unseen Masters of Scale and Vision, David Lund, Routledge, 2023.

[7] The Scotsman, 4 January 1939.

[8] Newcastle Journal, 15 December 1944.

[9] The Times, October 12, 1935.

[10] Birmingham Daily Gazette, 2 February 1937.

[11] Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press, 16 May 1936.

[12] The Scotsman, 20 February 1936.

[13] Thanet Advertiser, 25 February 1936.

[14] Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 20 March 1936.

[15] Coventry Evening Telegraph, 31 July 1935.

[16] Scheme & Estimate for proposed Belfast-Holywood By-pass Road, Ministry of Home Affairs, Stormont, December 1936. By R. D. Duncan. C/o Wesley Johnston.

[17] Evesham Standard & West Midland Observer, 7 November 1936.

[18] Western Daily Press, 06 December 1934.

[19] Dundee Evening Telegraph, 2 May 1936.

[20] Report by the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents (session 1938-39). https://archive.org/details/b32170312

[21] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1939/may/03/prevention-of-road-accidents

[22] Dundee Courier, 30 November 1937.

[23] Western Daily Press, 11 February 1937.

[24] Aberdeen Press and Journal, 12 June 1937.

[25] Daily Herald, 08 October 1936

[26] “Restrictions On Cyclists,” The Times, April 13th, 1938

[27] The Committee was appointed on the 15th October, 1936, and consisted of

Lieut. Col. Sir Seymour Williams, K. B. E. (Chairman),

Sir James Adam

Cecil O. Argles

Ernest Bevin, Esq.

Major Sir Robert Brooke

Sir Alexander Butterworth

S.E. Garcke, Esq.

W. H. Gaunt, Esq.,

J.J, Hughes, Esq.

J. Marchbank, Esq.;

J.H. Meachin, Esq.,

Sir John McDonald,

F.J. Urry, Esq.

[28] The Scotsman, 21 June 1938.

[29] https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1938-06-17/debates/fea4d459-3e65-4e38-9ea7-b6de0d8018e4/MinistryOfTransport

[30] Letter to Gordon Tucker, secretary, Transport Advisory Council, Ministry of Transport, 10th March 1938

[31] TAC’s Draft report “Accidents to cyclists,” 11th February 1938. MT43/72 National Archives.

[32] Daily Herald, March 23, 1938.

[33] Hull Daily Mail, 20 August 1938.

[34] INTRODUCTION OF CYCLING TRACKS, ROAD ACCIDENTS. HC Deb 07 February 1934 vol 285 cc1209-69

[35] Sheffield Independent , 16 March 1934.

[36] It was Stanley who first pushed for what later became zebra crossings and Belisha beacons. (There was a later parallel, of course, with Boris bikes — London’s cycle hire scheme was first proposed by London Mayor Ken Livingstone, not London Mayor Boris Johnson.) Oliver Stanley, House of Commons, 7 February 1934: “I have been for a long time interested, as many hon. Gentlemen must have been, in the experiment that has been taking place in Paris in authorised crossing places—what are called voies cloutées, which mark out passages for pedestrian crossing places. Certainly the figures which I have got from there are striking testimony to their success. In 1929 there were 254 of these pedestrian crossing places in use, and in that year the number killed in Paris was 328. In 1932 the number of pedestrian crossing places had risen to 8,954, and the number of deaths had fallen to 237. Impressive as these figures are, they are more impressive when one realises that during that same period from 1929 to 1932 the number of motor cars in the department of the Seine had increased by 50 per cent. The normal rate of increase therefore would have brought the deaths from 328 in 1929 to 492 in 1932, instead of which there were only 237. That is very impressive, and I do not think we can afford to close our eyes to an experiment of that kind, which seems to have been carried on with success.

I therefore decided some time ago to make an experiment on a large scale in London in the use of these pedestrian crossing places, and I have referred to the London and Home Counties Traffic Advisory Committee the whole of the question to suggest to me a scheme for the siteing and allocation of pedestrian crossing places.” HC Deb 07 February 1934 vol 285 cc1209-69. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1934/feb/07/road-accidents-1

[37] Manchester Guardian, December 15, 1934.

[38] Manchester Guardian, December 15, 1934.

[39] Hore-Belisha made similar comments when opening the 1934 Cycle and Motor Cycle Show at Olympia. http://www.aparchive.com/metadata/youtube/79eb36a039564858a2b76941451bf9fc.

Transport minister Leslie Hore-Belisha’s speech when opening the Motor Cycle and Cycle Show, Olympia, November 5-10, 1934:

In spite of the strong views from some quarters against the use of special tracks for cyclists, a number of correspondents have written to the Department in favour of such a provision.

It is curious that cyclist organisations stand almost alone in opposing or mistrusting the provision of special facilities for their use and safety.

Pedestrians clamour for footways and for field paths, and I am entirely in sympathy with their desire. Who has ever heard a Londoner complain that the construction of pedestrian subways at busy crossings constitutes a veiled attack on the pedestrian’s right to encounter perils on the carriageway? Horsemen and farmers urge

that grass verges should be provided for the benefit of horses and cattle.

Rotten Row appears, as far as one can judge, to be appreciated by horse-owners, who have never yet, I think, complained that it was part of an insidious campalgn to drive the horsemen off the roads. Why are cyclist organisations so suspicious?

When some benevolent local authority provides seats alongside a road, one does not hear Insinuations that

this is a sinister plot to prevent wayfarers from sitting on the grass.

It is remarkable that cyclists abroad regard special tracks as their rightful privilege, and I imagine that when English cyclists cross the Channel, they avail themselves gladly of these tracks

The opinions of foreign engineers, as the result of many years of experience are well summarised in a letter

addressed to my Chief Engineer by his opposite number in Holland a few months ago, viz:

“No traffic-betterment for motor traffic can take place, unless the cyclists have left the main road. They form a perpetual danger for themselves and for the motor traffic. In Holland, with the great number of cycles (2 millions on a population of 8 millions), all modern roads are provided with special cycle-tracks apart.”

+++

Enraged at the transport minister’s speech, the CTC sent him a letter of complaint, November 20, 1934:

That the Cyclists’ Touring Club protests against the remarks of the Minister of Transport on the subject of cycle paths, made at the opening of the Bicycle and Motor Cycle Show, and would remind Mr.Hore-Belisha that cyclists are opposed to the idea of such paths and are not prepared to give up their inalienable right to use the public highway; That a 2 1/2 mile stretch of cycle path cannot prove anything; and that the setting up of these paths does nothing towards dealing with the urgent problem of what he himself describes as ‘mass murder’ on our roads.

The Cyclists’ Touring Club desires to reiterate a passage from its recently published manifesto on Road Safety:

“If dangers exist, these should be removed or minimised, so that no road-user shall be placed in peril when engaged in the lawful and reasonable exercise of his rights.”

[40] Manchester Guardian, December 15, 1934.

[41] Manchester Guardian, December 15, 1934.

[42] Birmingham Daily Gazette, 26 March 1936.

[43] Birmingham Daily Gazette, 13 July 1936.

[44] BELISHA’S DESIGN FOR BOULEVARDS CARS, CYCLES, AND HORSES ALL CATERED FOR

A code for road-builders Has been drawn up by Mr Hore-Belisha, Minister of Transport. Recommendations on lay-out and construction are contained in a memorandum sent by the Ministry to the highway authorities. Chief proposals are: A minimum visibility between approaching vehicles on bends or on hills of 500 feet. Curves constructed with a minimum radius of 1000 feet. Curves should be banked wherever possible. A space of at least 440 yards between junctions. Guard rails or hedges between footpaths and carriageways wherever pedestrian traffic is heavy. Ample grass verges, with trees and shrubs so planted as to lessen headlight glare. Bridges or subways to carry major traffic routes over or under local roads. Light-coloured materials for road surfaces, to give better visibility at night. The Belisha roads would be equipped, too, with dual carriageways, cycle tracks, and in suitable cases grass tracks for horses. Other recommendations include:— The prompt removal of all obsolete or redundant road signs. The setting back off the main road of bus stops, so as to prevent any reduction in the traffic capacity of the road. Easily accessible parking places The provision of non-skid surfaces matter of ” primary importance.” The memorandum was prepared in consultation with representatives of the Institution of Municipal and County Engineers and the County Surveyors Society. Its recommendations are based on consideration of three main objects public safety, convenience of traffic, and preservation or enhancement of the amenities of the roads. The Minister, it is stated, specially desires that every care should be taken not merely to safeguard existing amenities, but to add to them.

Dundee Courier, 10 February 1937.

[45] HC Deb 01 April 1936 vol 310 cc1987-8 1987

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1936/apr/01/dual-carriageways#S5CV0310P0_19360401_HOC_148DUAL CARRIAGEWAYS.

[46] HC Deb 17 June 1938. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1938/jun/17/ministry-of-transport

[47] http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1934/apr/10/road-traffic-bill#S5CV0288P0_19340410_HOC_190