FOLLY & DANGER

Pedal on Parliament, Stop Killing Cyclists, and other such events protest the lack of Dutch-style cycleways on today’s roads. Conversely, in the 1930s, there were very well-attended protests against Dutch-style cycle tracks.

The protests were organised by the Cyclists’ Touring Club, the National Cyclists’ Union, the National Clarion Cycling Club, and several local cycling clubs.

The fear was that cyclists would be compelled to ride on what was considered inferior infrastructure. The first cycle track, installed in London in 1934, was sub-standard, but most of the 100 or so that followed were well-built.

Organised cycling didn’t seem to understand just how many cycle tracks were being built around the UK or that they were being built to an MoT master plan. There was little to no contemporary understanding from cycling writers that the MoT’s plans had been inspired and informed by the Dutch infrastructure ministry’s cycle track-building programme that favoured cyclists.

Many cycling magazine writers dismissed Britain’s cycle tracks because they were installed on arterial roads, where many “old-school” cyclists didn’t want to ride. (Others flocked to arterials because they got a buzz from the smoother, faster road surfaces). Cycling magazines were generally guilty of using photos and drawings of 19th-century style roads: meandering and bucolic. The CTC’s house magazine, for instance, did not feature illustrations of newfangled roundabouts, subways for pedestrians, dual-carriageway arterial roads, or separated cycle tracks. Visual representations of modernity appeared to be deliberately excluded. The cycling media mostly harked back to a golden age of cycling when there were only a tiny number of cars on the roads.

The magazines were aimed at recreational cyclists even though, by far, the largest bulk of cyclists at that time were using bicycles for transportation.

Cycle touring and racing were the main subjects in all the magazines, primarily written by a tight clique of middle-class regulars, many of whom had started cycling in the 1890s or even earlier. These writers had little good to say about the MoT’s cycle tracks, and editorials bitterly opposed their spread.

“In their own interests, cyclists are advised not to use them.”

There were other efforts at dissuasion — a caption in Cycling beneath a photograph of a young woman cycling on a wide, kerb-protected track on Lostock Road, Manchester, recommended that “In their own interests, cyclists are advised not to use them.”

Leading members of the cycle industry were also opposed to cycle tracks.

“A large gathering of cyclists attended the protest meeting at Walsall recently against the construction of cycle paths between Walsall and Birmingham,” reported a newspaper in March 1935. At this meeting, Sir Edmund Crane, the managing director of the Hercules Cycle Company, then one of Britain’s biggest bike firms, said that compelling cyclists to use cycle tracks over roads was tantamount to “theft.”

Officials from the leading cycling organisations also helped to organise on-the-ground protests.

The National Cyclists’ Union and the Cyclists’ Touring Club, assisted by local organizations, organised a protest meeting in Devonport, the constituency of transport minister Leslie Hore-Belisha in April 1935. He had only been in post a few months, but his rubber-stamping of his predecessor’s cycle track-building programme infuriated organised cycling.

At the Devonport meeting, CTC secretary Mr. G. H. Stancer moved the resolution:

“That this public meeting of citizens and voters deplores the ineffectiveness of present legislation to reduce road casualties, and deprecates the view of the Minister of Transport, as indicated by his approval of cycle paths, that the segregation of cyclists is a just method of minimizing the terrible toll of the road.”

J. E. Holdsworth, representing the National Cyclists’ Union, seconded the motion, which, a newspaper reported, was “carried unanimously.”

A mass meeting of cyclists was held in the centre of Liverpool in January 1935. Another was held in London in August of that year — 500 club cyclists met in Hyde Park before riding to the cycle tracks on Western Avenue, which they pointedly refused to ride along, choosing to cycle in formation on the main carriageway, three and four abreast.

“Miss Pamela Lacon of South Hill-avenue, Harrow, decided to retaliate on behalf of motorists,” reported a newspaper. “She did so by driving her motor-car up and down the cycle tracks until stopped by mobile police and told she would summoned for driving dangerously and negligently. Miss Lacon said that she would fight the case as she said she drove with great care and that there was no notice prohibiting cars from using the tracks.”

“[MoT] officials have declared that 96 percent of cyclists used the [Western Avenue cycle tracks],” sniffed a motoring writer for the Daily Herald, adding that “the census took place the same week as the great protest when hundreds of cyclists riding in a body ignored the [tracks].”

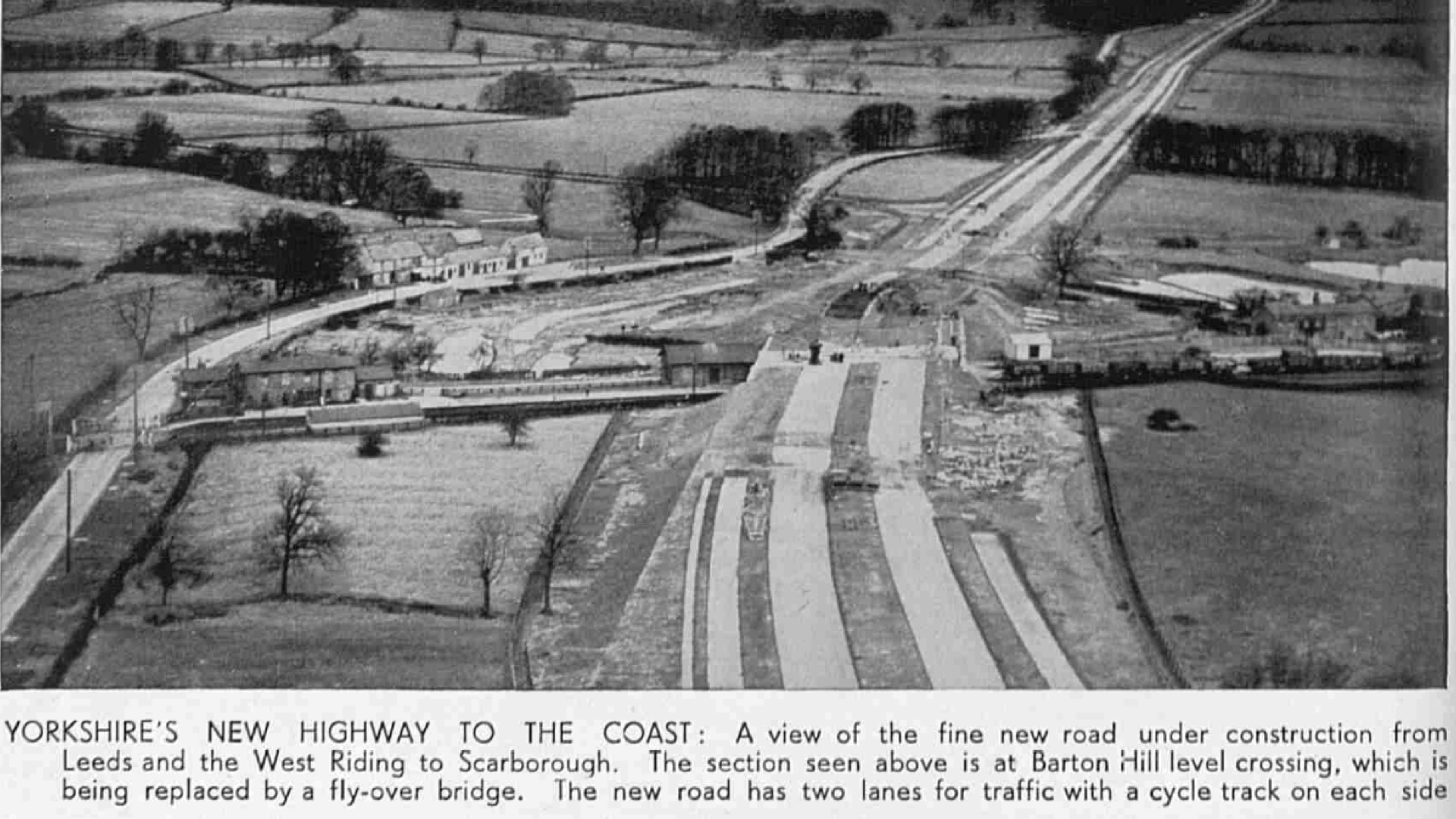

The Cyclists’ Touring Club organised protest rides against cycle tracks, including one in 1937, which blockaded the Malton bypass.

“Organisations claiming to represent 10,000 cyclists in Yorkshire are planning a mass ride on a section of road between York and Malton where cycling tracks have been constructed,” reported the Yorkshire Evening Post in May 1937.

“The proposal is to make a demonstration refusal to use them,” continued the newspaper.

The demonstration was arranged by local chapters of the Cyclists’ Touring Club.

C. A. Pratt, secretary of the Hull and East Riding Association, objected to what he claimed was the “folly and danger” of the tracks and suggested that “cyclist pickets should be stationed at the end of the paths each week-end to distribute literature urging cyclists not to use them.”

R. Sawtell, County Surveyor to the North Riding County Council, said: “I have heard that on Whit Monday, club cyclists were trying to induce the ‘private cyclist’ not to use the tracks.”

He added: “The private cyclist is using them. The club cyclists are not using them.”

NOTES

There were many other efforts at dissuasion – Cycling, August 10, 1936.

[2] Lichfield Mercury, 22 March 1935.

In 1939, Hercules made six million bicycles, making it one of the largest cycle manufacturers in the world.

[3] Western Morning News, 18 April 1935.

[4] Another was held – “More than 500 cyclists … cycled along the main road in club formation, and ignored the cycle path. . . . Earlier there was a meeting of the cyclists in Hyde Park at which a resolution was passed calling on the Minister for Transport not to proceed further with cycle paths, on the ground that cyclists had an equal right with others to the King’s highway.” ”News in Brief,” The Times, August 26, 1935.

[5] Gloucester Citizen, 28 August 1935.

[6] Daily Herald – Friday 13 September 1935

[7] Yorkshire Evening Post , 27 May 1937.