URBAN RENEWAL BUT FEW NEW CYCLE TRACKS

The Ministry of Transport’s cycle track building programme of the 1930s was not fully resurrected after the Second World War. Nor was it officially cancelled. Of the few new cycle tracks constructed in the 1950s, most had been planned in the 1930s and they still used 1930s-style cycle track designs.

However, there were stand-outs, using new plans, including the still-world-class cycle and pedestrian tunnels under the Tyne, opened in 1951; the short-lived 12-ft-wide cycleways of Coventry in 1957; and the construction, between 1951 and 1955, of the “cycleway” network of Stevenage.

The post-war atrophy of the MoT’s cycle track programme has to be seen in the light of austerity, the emphasis on a national house-building programme, and the creation of the National Health Service. Roads, too, were neglected; the government’s motorway-building frenzy did not take off until the early 1960s.

There was little cash for building new roads or cycle networks. The pre-war desire to encourage car ownership was resurrected in the various urban plans commissioned by cities. There was also a distinct difference in the way British and European cities were rebuilt after the war.

The Hanseatic-age Dutch-style merchant houses on Mariacka Street in the old city of Gdansk, Poland, were almost wholly destroyed between 1939 and 1945. Nearly 90 percent of the city was flattened in the conflict. In Germany, Münster suffered a similar fate. The historic cores of both cities and many more across Continental Europe, were rebuilt brick by brick.

The refurbishment of Gdansk was not like-for-like. Instead, for geo-political reasons, the recreation was modelled on the Polish city as it was in 1772 rather than that of an undamaged Gdansk of 1937. The city had been much modified in the 19th Century by German merchants, and the recreation harked back to a previous, less German era.

Such streetscapes are celebrated today, though they are facsimiles, but then, so is much of Hadrian’s Wall and Stonehenge. And like these UNESCO World Heritage sites, the recreated cities of Gdansk, Münster, Warsaw, Rothenburg, Freiburg, and others are valued for their authenticity, attracting tourists who swoon over the supposed historic originality.

Britain’s approach to post-war reconstruction was famously — and, arguably, disastrously — different. Bomb-damaged medieval, Georgian, and Victorian buildings were swept away in British cities after 1945 and replaced with modernist structures in the 1950s and beyond.

Local authorities embraced what they saw as modernity; they saw their cities as forward-thinking rather than stuck in the past; heritage was often junked and city plans focussed more on cars than people.

Architects, planners, local authorities, and property owners in Britain didn’t rebuild the old medieval cores of Coventry, Plymouth, and other bomb-damaged cities. Some individual buildings were rescued, but no city districts rose from the ashes, Gdansk-style.

Britain’s post-war Minister of Town and Country Planning, Lewis Silkin, visited Poland and called the reconstruction of Warsaw “an almost superhuman task.” (Back in the UK, Silkin oversaw the building of New Towns such as Stevenage.)

Coventry and the German city of Dresden were heavily bombed during the War. Still, while Coventry’s medieval cathedral was left as a shell, with a modernist replacement later grafted on, Dresden’s Frauenkirche was rebuilt.

That Dresden and Coventry commissioned opposing reconstruction methods is often assumed to be a 1950s choice. This is not so. Coventry’s council and the city’s pre-war chief engineer and chief architect were arguably more responsible for the destruction of Coventry’s medieval core than the incendiary bombs that rained down on the city in the early 1940s. The pair, backed by the modernity-fixated council, started to rip out the city’s medieval heart long before the war to create a city of Brutalist buildings with a motor-focussed ring road. These technocrats wanted to make Coventry — the hub of the domestic motor industry — into Britain’s Detroit, and they had motorways in mind before the wartime bombing raids that later, to their joy, hastened their plans.

Six hundred people died in the largest German raid, carried out on November 14th, 1940 — the first raid of the Blitz on Britain — yet Coventry’s young and brash Harvard-educated architect Donald Gibson said the destruction wrought by the Nazis had been a “blessing in disguise.”

Using a slang name for Germans, Gibson added: “The jerries cleared out the core of the city, a chaotic mess, and now we can start anew.” (That “we” included the City Engineer Ernest Ford.)

Gibson’s “chaotic mess” included many of Coventry’s historic buildings, which, today, would be considered highly attractive and certainly fitting for a city where, according to a 13th Century legend, Lady Godiva rode naked on horseback through the Early Medieval streets to protest against her husband’s taxation policies. Despite this resonant history, the medieval streets and their buildings were already being demolished in the late 1920s and early 1930s as part of what was called “slum clearance,” but which, in reality, was more about making space for cars.

The timber-framed gabled houses of Butcher Row, the Bull Ring, and St. Agnes Lane — which would be national tourist attractions today — were described by the city’s mayor at the time as a “blot on the city”; they were removed between 1936 and 1937 before Gibson’s appointment in 1938.

The city’s technocrat planners, with the 29-year-old Gibson to the fore, wanted to re-model the centre of Coventry, removing all that they considered dated, which was almost everything, including many of Coventry’s fine Victorian buildings.

In May 1940, six months before the bombing raid that destroyed much of Coventry’s medieval core, Gibson unveiled “Coventry of Tomorrow: Towards a beautiful city,” an ambitious plan to remodel the city.

While most of the city’s residents feared and hated the Nazi bombing raids, Coventry’s motor-myopic planners loved them.

“We used to watch from the roof to see which buildings were blazing and then dash downstairs to check how much easier it would be to put our plans into action,” Gibson recalled later.

These plans included a boulevard system of wide roads, footways, cycleways, and grass verges. All were built in the late 1950s, and Coventry — briefly — had the widest and best-built cycleway in Britain.

At 12 ft wide, the cycleway was three feet wider than even the best of the 1930s cycle tracks.

“The first section of Coventry’s proposed — £3 million inner ring road has been approved by the Minister of Transport,” stated a newspaper in December 1957.

“The first section — from London Road to Quinton Road — will be 439 yards long. It will comprise 24ft.-wide dual carriageways with a 10-ft-wide central reservation, dual cycle tracks, two footpaths, and verges.”

Gibson’s wide cycleways, built between 1958 and 1959, did not last long — they disappeared underneath road widenings in the 1960s.

While Gibson envisioned a motor-friendly city, building wide cycleways and footways shows that he didn’t plan for cars alone and had been influenced, at least in part, by the MoT’s 1930s cycle track programme. However, his wide boulevards soon filled with motor traffic, and his successors felt it was their civic duty to change them into motorways, burying the cycleways and footways in the process.

Residents at the time had few objections to the 1940 city makeover plans and mostly welcomed the post-war ones. Creating “modern” cities was all the rage. And because of its motor industry heritage, Coventry was the poster child for the expected future of (free-flowing) mass motorization.

Thanks to its many automobile factories, Coventry had a much higher than average rate of car ownership and use: in 1965, the city, which could be walked across in ten minutes, had 146 cars per 1000 of the population, while the national average was only 107. Coventry’s residents, therefore, perhaps desired the building of the A4053 inner ring road; few at the time mourned the destruction of the city’s innovative-for-the-time cycleways.

“[T]he necessity for an urban motorway, especially one which is so tortuous to navigate, is now debatable,” wrote Caroline and Jeremy Gould in their 2016 book, Coventry: The making of a modern city.

They added that were it to be “replaced by an at-grade boulevard with the level pedestrian crossings and cycle lanes Gibson intended, Coventry would be a much enhanced city.”

CITY PLANS

The UK parliament might have been largely in favour of the modernist reconstruction of post-war Britain, but it’s notable that the House of Commons — all but destroyed in the final night of the Blitz, 10th and 11th May 1941 — wasn’t “reimagined” but reconstructed as close as possible to the Gothic design of Pugin’s 19th Century original. In 1945, Winston Churchill said, “[I hope the Commons chamber] will be preserved intact, as a monument of the ordeal which Westminster has passed through.”

Elsewhere, however, it was a different story. “Plan boldly and comprehensively,” the Minister of Works and Building Lord Reith advised British city officials.

For their part, officials in many towns and cities commissioned modernist town and city plans, sometimes compiled by in-house architects and planners but more usually by fashionable rent-a-planners such as Thomas Sharp, who wrote plans for Exeter, Oxford, and elsewhere. Sir Patrick Abercrombie wrote plans for London, Plymouth, Hull, and more. (His plans for London spawned the car-centric New Towns movement and the building of Harlow, Crawley, Stevenage, and the rest.)

People on cycles were largely missing from these plans. Sharp, the author of Town Planning, a Pelican Book that sold 250,000 copies in 1940, was dismissive of cyclists, calling them “locusts.”

Regarding Oxford, he wrote: “Bicycles came in hordes, like locusts, upon the university towns … The bicycle … is one of the main causes of traffic congestion … [They] cannot be lightly dismissed as mere bicycles. A few locusts are of little importance. A swarm is a plague.”

Sharp wanted to cleanse towns of such plagues. The future was to be motorized, and archaic bicycles had no place in such (popular) visions of modernity.

Sharp was far from a lone voice. The “elimination of pedestrians and cyclists would make for a more efficient road because drivers would be able to drive with a greater sense of security and safety,” stated Gloucestershire’s county surveyor in 1943.

Removing pedestrians and cyclists would lead to a “saving in the cost of construction of footways and cycle tracks,” added E.C. Boyce.

“Existing trunk roads would be adequate to provide for cyclists and pedestrians and would be safer because fast and long distance motor traffic would be removed to the [planned] motorways,” imagined Boyce.

People were “promised cheap motoring after the war,” and Boyce “thought it reasonable to assume that the number persons who would own cars would be double the pre-war total.” Therefore, he concluded it “was probable that cyclists would be reduced in number.”

A 1942 report from the Ministry of War Transport recommended that British cyclists should be provided with cycle tracks, but the report’s author, Sir Herbert Alker Tripp, acknowledged the defects in existing tracks:

The use of cycle tracks, as in Holland and Denmark, is regarded by many people as the main hope. Unfortunately, cycle tracks break off at all junctions, which are just the spots where accidents are most frequent and protection is most needed. Nor are the cycle tracks themselves as good as they sound. At the entry of every minor road the cyclist finds he has to bump over the gutter and camber of the minor road; motor vehicles trying to emerge from these roads pull right athwart his track … mothers and nursemaids with perambulators use the ramps at the road junctions and thus obstruct the cyclists…

Tripp was a police officer, town planner, and poster artist (all simultaneously — twenty of his bucolic watercolors were reproduced as posters for railway companies). As assistant commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in the 1930s, he was responsible for London’s traffic. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Tripp was a “passionate motorist and cyclist” and was especially interested in reducing the death toll on Britain’s roads. This, he felt, would be best achieved by training cyclists and pedestrians in the new road order: motorists now came first. When nonmotorized road users bristled at his suggestions, he came to believe that physical persuasion would have to be employed instead — pedestrians should be penned in at road crossings, and cyclists should be corralled on tracks. Gentlemen of education and position in their fast motorcars would be less likely to be caddish if they were given free rein on roads, he felt. And for that to happen, the only solution would be to separate transport modes. Perhaps instructively, Tripp preferred the word segregation.

Tripp developed his ideas in his 1942 study, Town Planning and Road Traffic, recommending car-free, pedestrian-only shopping precincts and bridges and underpasses in town centres to keep pedestrians and cyclists apart from motorists. Critics complained that this would mean drivers would get ground-level access to the streets, but all other users would have to climb into the sky or creep underground. Such plans were broadly welcomed by the establishment of the day — Tripp was especially popular in America — and architect and town planner Colin Buchanan later adopted the ideas in his team’s internationally influential 1963 report, Traffic in Towns.

“On [the] heavily trafficked by-pass, the formation of cycle tracks should be considered, particularly in the neighbourhood of works and factories,” stated Sir Charles Bressey in 1944. Bressey was the MoT’s chief engineer who led the building of the first cycle tracks and he was quoted in “New Roads for Britain” from the British Road Federation. This 60-page booklet was written by George C. Curnock and in it he advocated for motorways and and arterial ring roads around cities.

“Whenever possible the cyclist should be segregated both from other road traffic and from pedestrians,” the booklet stated. “There must be adequate cycle tracks between residential and industrial or recreational districts in all areas where the use of cycles is very considerable, and along radial and arterial roads.”

Bressey was not one of the town planners appointed to a 1943 Ministry of War Transport committee looking to reconstruct postwar Britain. Still, his influence can be seen throughout the committee’s report, published in 1946. Design & Layout of Roads in Built-up Areas recommended segregated provision for the growing number of cyclists, worrying that “conditions obtaining in early postwar years will tend still further to popularize the cycling habit.” Nevertheless, the team led by Sir Frederick C. Cook believed there was a strong case for the “necessity of making ample road provision for pedal cyclists.”

Wartime casualty figures led the report’s author to the “inevitable conclusion that by far the best preventative of accidents to pedal cyclists lies in their segregation from motor traffic, for it is clearly unsound that a running surface should be used at one and the same time by heavy motor-driven vehicles capable of developing high speed and by light and unstable vehicles such as pedal cycles.”

The 104-page Design & Layout of Roads in Built-up Areas had technical drawings showing how cycleways should be carried around roundabouts, offering continuous protection.

When the publication argued that new arterials should have separated cycleways running alongside them, this wasn’t theoretical; it had been carried out, with much trial and error, for at least twelve years prior to the guide’s publication.

“The profile of tracks should be unbroken across intersecting vehicular entrances, and they should approach side roads with an easy ramp.” The report also suggested that the “surface is best formed by materials of pleasingly distinctive colour.”

(Manchester’s Lostock Road cycleways were capped with red concrete, and it’s likely other cycleways elsewhere in the country were also distinctively coloured.)

The width of tracks should be 9 feet, stated the report, separated from adjacent footways by a low curb and from the carriageway by a 6-foot verge. (That is, exactly the dimensions of the best 1930s cycle tracks.)

Design & Layout was a fleshed-out version of various Memorandums issued by the Ministry of Transport; the first was issued in 1930, followed by a revised edition in 1937, and the further revised Memorandum No. 575 of 1943. This called for “Cycle tracks, footpaths, and suitable crossings for pedestrians” beside and on the new “arterial” roads and bypasses still being constructed in the war years.

Interestingly, as well as using the phrase “cycle tracks,” Design & Layout also introduced the phrase “cycle ways”. Paragraph 208 said: “The principles underlying the provision of pedestrian ways could advantageously be applied to well-surfaced ‘cycle ways’ for the exclusive use of pedal cyclists, separate from the general road system and of width sufficient for two-way traffic. In towns where pedal cycle traffic is intense, a material contribution could thus be made to safety and the relief of congestion on public highways.”

Cook and his fellow authors recommended the provision of wide kerb-protected cycleways, not the thin paint-only “bike lanes” that cyclists were later provided with.

“It has been suggested,” wrote Cook, “that strips of the carriageway adjacent to the herb might be regarded as primarily for the use of pedal cyclists. We disagree with this suggestion. Whatever methods were adopted for indicating the reserved strips, whether by special colour or other means, they would have to be used by vehicles drawing alongside the kerb.”

Predicting what eventually did happen, Cook said that “other road users could not be relied upon, nor indeed expected to regard [the strips] as sacrosanct to pedal cyclists, and the latter would then have been led into a false sense of security.”

For Cook, segregation was for safety reasons. “By far the best preventative of accidents to pedal cyclists lies in their segregation from motor traffic,” he argued, “for it is clearly unsound that a running surface should be used at one and the same time by heavy motor-driven vehicles capable of developing high speed and by light and unstable vehicles such as pedal cyclists.”

Cycleways were to be “well-surfaced” and “for the exclusive use of pedal cyclists, separate from the general road system and of width sufficient for two-way traffic.” “Segregation … should be the key-note of modern road design,” stressed Design & Layout. “Police supervision would be necessary to ensure that … cycle ways are not used by other classes of traffic or otherwise abused,” and such “segregated tracks for cyclists” should be provided “as a matter of course on arterial, through- and local-through routes…”

Postwar austerity meant few new tracks were built, and the 102 or so existing ones needed to be improved to the standard that cycling organisations said would be required. Had the cycling organisations of the time welcomed the cycle tracks, it would have made no difference. In the 1940s and 1950s, there was little appetite to provide for cyclists despite the fact they still far outnumbered motorists. Cycling levels peaked in 1949 when 15 billion miles were ridden by cyclists, representing 37 percent of all journeys, which is higher than the cycling levels in the Netherlands today.

Postwar politicians and planners were deeply dismissive of “proletarian” mass cycling — instead, they were attracted to the social and economic potential of motoring. It was felt that cycling was not suited for the motor era and most certainly not worth spending any money on.

People wanted to own and drive motor cars, it was believed, and when they could give up their bicycles, they did.

While some British cities took the opportunity to clear “slums” (many medieval buildings disappeared this way) and create new shopping and commercial precincts and zones, there was a great deal of emphasis on making more room for motor vehicles, with roads widened, and impromptu car parks made official.

Shortages of raw materials and labour meant many of the post-war city plans didn’t start to be built until a decade or so after they were published, and by then, they had been watered down.

Thanks to post-war investment in Continental Europe, much of it American, many cities had rebuilt much of their central cores by 1955. Britain’s 1947 Town and Country Planning Act empowered towns and cities to “improve” their streets, often with motor traffic front of mind.

The ministries of planning and health imagined a car-based future. Similarly, the focus of the MoT was very much on the motoring hegemony to come, which the ministry would help create. Little was done to encourage cyclists because cycling was assumed by many to be an outmoded form of transport and one that would soon whither and die.

Prewar designs were used in the few cycle tracks that did get built in the late 1940s and 1950s, and many more such cycle tracks were planned but appeared not to have been built. The cycle and pedestrian tunnels under the Tyne and the cycleways of Stevenage, discussed below, are outliers.

Some of the post-war cycle tracks with 1930s designs are included in the list of 102-period cycle tracks. These include:

- Longforgan, near Dundee, partially completed in 1939 but not fully opened until 1946,

- Farnham bypass, near Aldershot, partially completed by 1940, but the central section was not completed until 1957.

- Kesgrave, near Ipswich, probably built in the 1960s.

- Kidlington in Oxfordshire, opened in 1950.

- Longton bypass, near Preston, was planned in 1937 but not opened until 1957.

What follows are those cycle tracks that don’t fit into the list of 102 cycle tracks either built or designed in the 1930s and early 1940s. The modern-style cycle tracks of the 1980s and 1990s and beyond are beyond the scope of this study.

FORTH ROAD BRIDGE, 1946

The Forth Road Bridge, connecting Edinburgh with Queensferry across the Firth of Forth, was opened in 1964 but was first proposed in 1923, winning the support of the Ministry of Transport the following year. In 1947, the Forth Road Bridge Order established the submerged Macintosh Rock as the site for the new road bridge. Construction started in 1958, and when finished, the bridge had 9-ft-wide cycle tracks and 6-ft-wide footways, the exact dimensions of 1930s cycle tracks and footways

A newspaper reporting on the proposed bridge in 1946 wrote: “The accommodation provided for traffic consists of two carriageways, each 22 feet in width, two cycle tracks 9 feet wide, and two footpaths each 5 feet wide.”

TYNE TUNNEL, 1951

Complete separation of modes is the gold standard for bicycle- and pedestrian-friendly infrastructure. Therefore, the Tyne Pedestrian and Cyclist Tunnels can be considered platinum standard because there are wide, separate tunnels for those on foot and those cycling.

The 275-metre twin-tube tunnel is buried 12 metres beneath the River Tyne between Jarrow and Howdon, near Newcastle in northeast England. It was opened in 1951, sixteen years before the Tyne Tunnel for motor vehicles. At its peak, soon after opening, 20,000 users rode or walked through the tunnels each day.

At 3.7 metres wide, the cyclists’ part of the Tyne Pedestrian and Cycle Tunnels is almost a metre wider than the world-class cycleway along the Thames Embankment in London.

Built as Tyneside’s contribution to the post-war Festival of Britain staged between May and September 1951, the tunnels linked shipyards on both sides of the Tyne. The shipyards are long gone, and the tunnels will likely never again cater to 20,000 users a day, but cyclists and pedestrians cannot use the motorist-only Tyne Tunnel. There’s no bridge nearby, so the route — open 24 hours a day — is critical for those without motor vehicles but wishing to cross the river at this point.

Unlike the Tyne Tunnel for motorists, access to the cyclist and pedestrian tunnels has always been free. The nearby Shields ferry is not free.

The Tyne Pedestrian and Cycle Tunnels were built at the location of a second ferry over the Tyne, which went out of business soon after the tunnels opened.

The Tyne Pedestrian and Cyclist tunnels were officially opened on 24th July 1951. Durham and Northumberland County Councils gave the scheme the go-ahead in 1938, although plans for tunnels have been much discussed since the 1920s. In the early 1900s, there were plans for a railway tunnel beneath the Tyne, with guaranteed bicycle passage.

The 1938 plan for the tunnel was shelved in the run-up to the Second World War but resurrected in 1946 when the UK parliament passed the Tyne Tunnel Act. There were originally plans to build the motor-vehicle tunnel soon after the cyclist and pedestrian tunnels, but Minister of Transport John Boyd-Carpenter put these on hold “until the country’s economic situation has improved,” reported the Sunderland Daily Echo in July 1951.

Construction on the tunnels started in 1947, a year before the UK government introduced the Special Roads Bill. This law would lead to the creation of Britain’s motorway network, beginning in 1958. But the bill also promised “special roads for cyclists.”

In 1948, the modal share for cycling in Britain was 25% or roughly the same as Dutch levels today, but cycling then went into a steep decline, bottoming out at a 1% modal share by 1970. In a little over 22 years, cycling went from a mainstream form of transport to an ignored, denigrated one.

There are other cycle and pedestrian tunnels in the U.K. — including under the Clyde in Glasgow and the Thames at Greenwich — but the Tyneside tunnels are of a much higher standard. Riding through the cyclists’ tunnel is a delight — there’s no wind, and from the Jarrow side, there’s a curved descent.

It’s likely the Tyne Pedestrian and Cyclist Tunnels were modelled on a similar tunnel system in Rotterdam in The Netherlands, built between 1937 and 1942. This connects the two banks of the River Nieuwe Maas and includes separate tunnels for pedestrians, cyclists, and motorists.

BEDFORD, 1952

According to a 1935 Ministry of Transport census, cycles accounted for 80% of the vehicular traffic in Bedford. Ten years later, a town council traffic census compiler complained of the “difficulty” in counting because “for ten minutes in one midday period cyclists passed the census-takers at the rate to three thousand an hour.”

Despite this remarkable level of cycle use in Bedford, there was little provision for cyclists but much planning was done to cope with congestion caused by motor traffic. When discussing the town’s western bypass in 1949, a road suggested by the Ministry of Transport, Bedford’s town planning committee agreed that cycle tracks would also be required to be built.

A pedestrian-and-cycle track would have to link the “Slipe, Queen’s Park, with Granville and Stafford Roads on the south bank,” and three others would also be required.

A newspaper reported:

“Another continues the line of Mile Road westward across the Bletchley railway line and emerges into Ampthill Road. The third connects Elstow Road with Sandhurst Road by spanning the Cambridge railway line; this track has its eastern extremity the corner of Elstow Road and Conquest Road. The other track begins at the eastern end of Conquest Road and crosses the Hitchin branch line to link up with the London Road at a point near its junction with Faldo Road.”

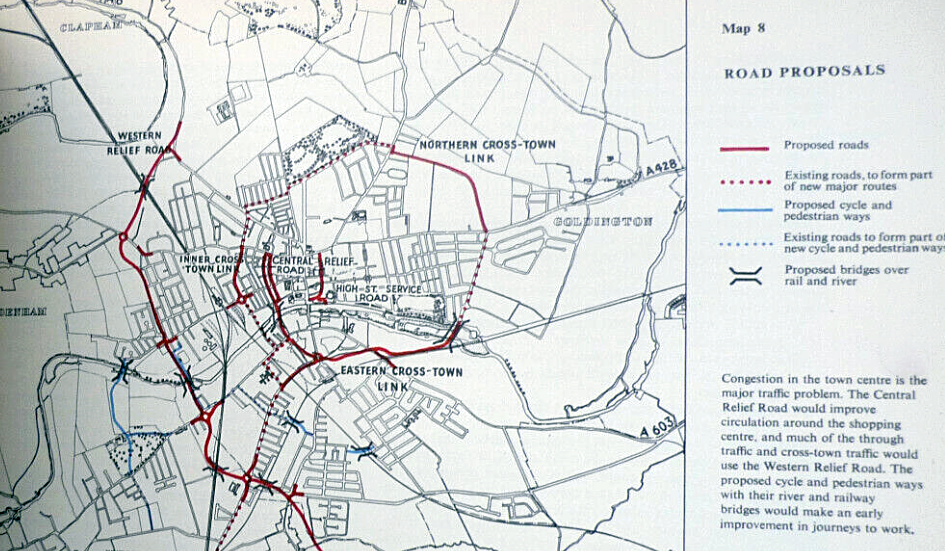

Bedford Town Council was advised by the Max Lock Group, an architectural and town planning consultancy headed by Max Lock. The Group’s “Bedford by the River” report of 1952 proposed the four routes above, which consisted of “cycle and pedestrian ways” over rail and river bridges.

Some of the four ways were completed by 1953.

STEVENAGE, 1955

While the post-war powers that be mostly legislated for a car-shaped future, some officials thought bicycles would loom large, at least for the proposed New Towns. Designated under the New Towns Act of 1946 and built mainly for the working classes bombed out of their houses and soldiers returning from war, the New Towns were “fit for heroes to live in.”

Designed when petrol rationing remained in force and cycling was still a dominant mode, the New Towns would be laced with 1930s-style cycle tracks, portrayed in a 1948 animation commissioned by the Central Office of Information.

Charley in New Town was produced by husband and wife John Halas and Joy Batchelor, who ran the Halas & Batchelor Cartoon Films business. The studio was formed in 1940 and was the UK’s largest and most influential producer of animated films until the mid-1970s. Charley was an “everyman” created for the Central Office of Information¬†at the behest of then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir Stafford Cripps.

Charley starred in eight humorous films examining topics such as national insurance, the National Health Service and other aspects of new state interventionism ushered in by Labour’s victory at the 1945 General Election.

Charley started each film riding his bicycle and, in the nine-minute film introducing New Towns, he stayed on his bicycle throughout, bouncing along cycle tracks, not roads. There were trucks in this film, but no cars. New Towns, explained the film’s narrator, would be utopias where residential areas would be “not more than five minutes travel from home to work which means making cycle tracks and byroads” to link with the zones dedicated to industrial use.

The utopia portrayed in this film was clearly based on the plans for Stevenage in Hertfordshire, thirty miles north of London, which would be the first of Britain’s New Towns, laid out between 1951 and 1955. It was laced with cycle tracks and footways adjacent to the town’s roads; cycle tracks wider and better designed than those constructed in the 1930s. Cyclists need not interact with motorists because both have their own infrastructure.

According to Tim Jones, an academic expert on traffic-free trails, the interconnected cycle infrastructure of Stevenage was designed to “produce maximum attraction, comfort and safety.” Cyclists were

… provided with their own segregated junction by elevating the road by two metres and lowering the cycleway one metre to obtain a compromise in achieving the three-metre difference in level. This design was crucial in recognising that cyclists could be deterred by difficult gradients and also allowed good forward visibility to improve perceptions of personal safety. Routes were lit with overspill light from road lighting. The ten approach possibilities into the town centre were colour-coded on a signpost system and facilities for the storage of cycles were considered at end destinations such as the town centre and railway station.

Stevenage was planned by chief engineer Eric Claxton. He was a junior engineer in the Ministry of Transport from 1935 to 1939, cycling 18 miles to and from work daily.

“The era of dual carriageways had begun [in the 1930s] and I found myself entrusted with the design and construction of bridges to accommodate them and the roads to cross them,” he wrote in his memoirs, published a year before he died in 1993.

He also helped design the cycle tracks adjacent to the dual carriageways.

“Decisions,” he said, “were taken to create cycle tracks after the pattern of those to be found … in Holland. I built some miles of these under direction from above …”

But the cycle tracks he worked on were sub-standard, admitted Claxton. “As a cyclist they gave me no satisfaction,” he admitted:

The [cycle tracks] were too narrow. They were made of concrete and suffered from either cracking or construction joints. They provided protection where the carriageway was safe but discharged the cyclists into the maelstrom of main traffic where the system was most dangerous. For me worst of all the tracks were uni-directional either side of the dual carriageways; thus if for any reason one needed to retrace one’s way, one was compelled to run the gauntlet of crossing the streams of traffic on both carriageways to return on the far side — woe betide the person who left money, keys, books, tools or even lunch behind.

The worst problem, continued Claxton, “was being turned back into the main traffic streams at major junctions and I was busy fighting this when the war broke out. I was too junior then to cut much ice, but I kept on plugging away at it, cudgelling my brain as how best to overcome the worst of these hazards.”

When given the task of shaping Stevenage, Claxton was determined to avoid making the same mistakes as his MoT superiors. He called his cycle tracks cycleways to differentiate them from the MoT’s 1930s-style cycle tracks. They would be designed with scientific precision: “We were in an era about to give birth to a whole new technology,” said Claxton.

Construction of the cycleway network was given the go-ahead in 1950, and it was built at the same time as the primary road network.

A 1958 annual municipal report said: “Segregation for those who wish to avail themselves of it begins about half a mile from the centre of the Industrial Area and at peak traffic times the separation of pedestrians and cyclists from the main stream of traffic is an advantage to all types of road users.”

The cycleways were primarily flat, and there were cycle and pedestrian bridges and underpasses, which would not have looked out of place in the Netherlands at the time, mainly because they were modelled on Dutch infrastructure. Stevenage was compact, and Claxton assumed the provision of 12-ft-wide cycleways and 7-ft-wide footways — separated at a minimum by grass strips and sometimes by barriers, too — would encourage residents to walk and cycle. He had witnessed high usage of cycle tracks in the Netherlands and believed the same could be achieved in the UK.

Instead — to Claxton’s puzzlement and eventual horror — residents of Stevenage chose to drive, not cycle, even for journeys of two miles or less. Stevenage’s 1949 masterplan projected that 40 percent of the town’s residents would cycle daily, and just 16 percent would drive. The opposite happened. By 1964, cycle use was down to 13 percent; by 1972, it had dropped to 7 percent.

Claxton was the chief engineer of Stevenage until 1972. He scorned those who chose motorcars over bicycles, complaining that motorists “seem to have a problem with their logic” because “they use their cars as shopping baskets, or use them as overcoats.” Claxton complained that he had provided “cycle tracks [modeled on the] pattern of those found [in] Holland” for the residents of Stevenage, but cycle use in Stevenage never reached Dutch levels of use.

Stevenage New Town was essentially Claxton’s creation. He had worked on the New Town plan from 1946 and, despite having superiors brought in above him, much to his chagrin, it was he who was in charge of where to place the sewers; he who decided where the new roads would go; he who decided whether or not there was to be a boating lake (there was, he built it at the insistence of his daughter, a primary-school teacher who wanted somewhere scenic to take her class). It was he who insisted that cycleways should be a key and wholly interconnected part of the town’s transport system. He had to fight for funding, but, sometimes by stealth, he managed to secure permissions for his 23 miles of cycleways and his 90 underpasses.

Dr. Alex Moulton, designer of the eponymous bicycle — the 1960s ride choice of society elites — said the Stevenage cycleway system was a “wonderful creation” and its designer a “prophet.”

Evelyn Denington, chair of Stevenage Development Corporation from 1965 until it was wound up in 1980, said in 1992: “One important feature of the town is its segregated cycleways which duplicate the main arteries and feed both the housing and the industrial areas. Mr. Claxton was a keen cyclist and was well aware of the need to cater for this enjoyable and excellent mode of travel.”

“I didn’t do my cycleways for cyclists,” Claxton told an environmental magazine in 1977. “I did them for people.” He had no truck with cycling campaigners. When he was a MoT junior engineer in the 1930s, he wrote to the Cyclists’ Touring Club asking for feedback on the cycle tracks he had helped to plan. “Imagine my dismay,” he recalled, “when I received a rather dusty answer from the general secretary. CTC wanted nothing to do with cycle tracks and demanded the freedom to use the carriageway — it seemed I had been added to their list of devils hell-bent on snatching away such freedom.” (In the 1960s and 1970s, CTC welcomed Stevenage’s cycleways, and the organization gave Claxton honorary life membership for “services to cycling.”)

“Organised cycling rejected the [1930s cycle tracks],” he wrote. “However, organised cycling changed its opinion when the Stevenage New Town system had reached a sufficiently advanced stage to be assessed.”

British local authorities asked Claxton to evaluate cycleways for their towns and cities — he helped Peterborough plan 38 miles of “cross-city cycleways,” separated from motor traffic, and 34 miles of “secondary routes” designated as “cycle priority streets.”

Ladybird’s The Story of the Bicycle of 1975 lauded Stevenage for its “careful planning” and said that the “dangers of mixing with heavy traffic on main roads can be overcome with the use of ‘cycle only’ roads, called cycleways.”

AINTREE, 1957

The 9-ft-wide cycle track beside the A59 at Old Roan, Aintree, was built between 1957 and 1958 to link with 1930s-era cycle tracks on Dunnings Bridge Road, south of Maghull.

“The Old Roan road bridge over the Leeds-Liverpool canal, a landmark familiar to millions of Grand National steeplechase followers, is to be rebuilt part of a £227,000 road widening and improvement scheme on the Liverpool-Leeds trunk road A59 at Aintree,” reported a newspaper in January 1956.

“For a length of about 1,400 yards, there will be dual two-lane carriageways, in addition to footpaths and a nine foot cycle track …” continued the report.

“The scheme has been designed for the Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation by the Lancashire County Council through their Surveyor and Bridgemaster Mr. James Drake.”

According to a 1958 update on road building from the Ministry of Transport, the works included the “provision of dual 22 ft. carriageways [and] cycle tracks and footpaths, including the reconstruction of the Old Roan Canal Bridge, Length, 1,400 yards.”

OXTON BYPASS, 1956

“Dual Carriage Ways and Cycle Tracks of a new by- pass road, two miles long, skirting the village of Oxton, will begin shortly,” reported the Nottingham Journal in April 1939.

“The road of concrete will have an overall width of 100 feet. There will be dual carriageways, cycle tracks on both sides and footpath one side.”

A 1.5 mile northern section of the road was opened on 24th March 1942, but one carriageway only and probably without an adjacent cycle track. The southern section, with dual carriageways, was opened in 1956. Space was left for a cycle track, but this likely wasn’t added in 1956. However, there’s a 350-metre stretch of road with an adjacent something or other. It looks like an extremely long lay-by or third lane, but there is no need for either on this road, and indeed not of this length. This redundant stretch of road may be a remnant of a 1950s cycle track.

BRITON FERRY, 1958

A 1958 road building update from the Ministry of Transport reported on the “construction of a new road between Briton Ferry and Earlswood, incorporating a 90 ft. layout with dual 22 ft. carriageways and cycle tracks.”

The two-mile road might have been built at the end of the 1950s, but it had been planned in the 1930s.

“Glamorgan County Council [proposes] to construct a £78,000 road and bridge scheme to by-pass Neat,” reported a newspaper in December 1937.

“In the first stage the [Briton Ferry] road would be 84ft. wide, comprising two 22ft. carriage ways, a central 6ft. strip, two cycle tracks 6ft. wide, and two paths 6ft. wide, with 3ft. and 2ft. divisions between the carriage ways and cycle tracks and cycle tracks and footways respectively,” continued the newspaper.

There are cycle tracks on both sides of the road on the Briton Ferry bridge, and one cycle track extends for the full 1.97 miles of the 1958 road.

HUNTINGDON BYPASS, 1957

In an illustration accompanying a 1957 plan from H. J. Longstaff, the county surveyor for Cambridgeshire, 1930s-style cycle tracks were nailed on for the proposed Huntingdon bypass. This was eventually built, but not until 1973; the final version dispensed with the cycleways.

THATCHAM, 1958

There’s a footway/cycleway of some sort on the Bath Road at Thatcham in Berkshire, but it probably wasn’t built in the 1950s. This can be surmised from an interesting complaint lodged with the Ministry of Transport from a District Council in 1958.

According to a newspaper report in August of that year Newbury District Council wrote “to the Minister of Transport asking him why a cycle track was not provided when the main Bath Road was recently reconstructed between Thatcham and Colthrop.”

The council was “concerned about the safety of large numbers of cyclists travelling between Newbury and Thatcham Mills.”

The Minister stated that “it was the department’s policy to provide tracks where they were justified on new roads or when existing roads were re-constructed.”

The Minister added: “The census of traffic recently carried out shows it has reached the volume which would ordinarily justify cycle tracks between Colthrop Mills and Newbury, but it is regretted that after very careful consideration a scheme for their provision cannot be authorised at the present time.”

CLIFTON BRIDGE, 1958

Nottingham’s Clifton Boulevard cycle tracks date to 1938. Further on, there’s a link with cycle tracks on Clifton Bridge. This bridge over the Trent opened in 1958 and provided with 1930s-style cycle tracks and footways. Four children can be seen cycling along the tracks in a photograph taken in the same year.

The cycle tracks and footways were reduced in width when additional lanes were added to the bridge in 1972.

SYDENHAM BYPASS, BELFAST, 1959

In 1936, Scottish consulting engineer Robert Dundas Duncan reported on the feasibility of constructing a two-and-a-half-mile-long bypass of East Belfast. He was subsequently commissioned to build this Belfast to Bangor road, called the A2 Sydenham bypass, which was to be the first dual carriageway in Northern Ireland. It was to be equipped with “cycling tracks,” reported a newspaper.

“[It] would seem very short-sighted to omit accommodation for cyclists, not only in the paramount desire for safety but to enable the width of the main carriageway to be kept as small as possible,” stated Duncan in his report, recommending 6-ft-wide cycle tracks each side of the road.

Although he stated cycle tracks were for the safety of cyclists, the real motivation was control:

“Cyclists, even when perfectly disciplined, occupy a disproportionate area of roadway, and it is not financially sound to allow them the use of an 8” thick concrete slab when one 5” or 4” thick is sufficient. One cycle track 5 feet wide can be obtained for the cost of widening the carriageway by 2 feet. Further, the removal of cyclists from the carriageway allows vehicles to use the inner lane with perfect safety, and without subjecting both drivers and cyclists to the constant nervous tension produced by their mutual presence.”

Duncan started building the road in 1937, and work continued for two years, but it was not completed before the outbreak of war.

“Lady Bates, wife of the late Sir Dawson Bates, Bt., then Minister of Home Affairs, in December 1937, cut the first sod,” reported the Belfast Telegraph in October 1950, recounting the “melancholy story of the by-pass road that was begun but not completed.”

It took a further nine years before the road — complete with 1930s-style cycle tracks and footways — finally opened on 23rd November 1959.

“The cycle tracks continue in subways at the Tillyburn roundabout to give access to and from the Holywood Road,” stated the Telegraph in November 1959.

“Work to convert the cycle track to a hard shoulder” was commissioned in 1976.

The following year, “about 300 metres of cycle track [was] converted to hard shoulder,” stated the Telegraph.

Later works have resulted in a Stevenage-style underpass for cyclists and pedestrians beneath a former roundabout close to Belfast City Airport on the A2. “The Knocknagoney junction used to be a roundabout but was altered to improve flow in the early 1990s,” states Northern Ireland roads expert Wesley Johnson.

KIDDERMINSTER, 1971

The dual carriageway widening the A451 Minster Road between Kidderminster to Southport was opened in July 1971. It featured intermittent adjacent cycle tracks likely built at the same time as the expanded road.

The need for the cycle tracks had been identified in 1936.

“A stretch of road between [Kidderminster] and Stourport, where several accidents have occurred, came under discussion,” reported a newspaper in May of that year.

“The Council referred back to the committee a proposal for road widening, which made provision for a carriageway of 30ft, two 7ft 6in. footpaths and two 7ft 6in. cycle tracks.”

(These are unusual widths for period cycle tracks and footways.)

“Councillor G. S. Tomkinson did not want the cycle tracks cut out for there were an enormous number of cyclists using the road,” continued the newspaper.

The 1970s cycle tracks are still wide today in parts and veer away from the road at times, which wasn’t a feature of 1930s cycle tracks.

NOTES

[1] The 1950s New Town of Harlow also had cycleways, but far fewer than Stevenage and none followed the main roads. The “Redway” pedestrian and cycle network of the 1960s New Town of Milton Keynes was originally the pedestrian-only “Pedway” network.

[2] “All too often, the planners cut the heart out of our cities,” Margaret Thatcher said her Conservative Party Conference speech, 9 October 1987. “They swept aside the familiar city centres that had grown up over the centuries.”

[3] ‘Impressions of a Recent Visit to Poland and Czechoslovakia,’ Lewis Silkin, 1947, National Archives UK (TNA): CAB 129/22 [CP (47) 343, 31 Dec 47.

[4] But only comparatively recently with the 15-year reconstruction completed in 2005.

[5] Birmingham Daily Post, 4 December 1957.

[6] Hansard, 25 January 1945

[7] House of Lords Debates ‘Post-War Reconstruction’, HL Deb 17 Jul 41 https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/1941-07-17/debates/7bf1dc59-52c4-439a-a0d8-40753fe1ade5/Post-WarReconstruction

[8] Oxford Replanned, Thomas Sharp, 1948.

[9] Gloucester Citizen, 2 November 1943.

[10] The use of cycle tracks, as in Holland and Denmark, is regarded – Herbert Alker Tripp, Town Planning and Road Traffic, E. Arnold & Co., 1942.

[11] According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Tripp – Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, May 2013, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/98024 .

[12] Dover Express, 18 August 1944.

[13] Aberdeen Press and Journal, 15 December 1944.

[14] **The team led by Sir Frederick C. Cook believed – *Design & Layout of Roads in Built-up Areas*, Ministry of War Transport, HMSO, 1946.

[15] *Wartime casualty figures led the report authors –* Sadly, road travel was awfully dangerous during the war, especially at night with cars traveling with dimmed lights because of black-out rules. An astonishing 9,169 people lost their lives on the roads of Britain in 1941, almost 3,000 more than during prewar years.

[16] In short, motorists wanted cyclists off the road, and cyclists wanted cars, a rather vicious circle.

[17] Ministry of Town and Country Planning, The Redevelopment of Central Areas, London, 1947. Report of the Ministry of Housing and Local Government for the Period 1950/51 to 1954 London, 1955.

[18] https://www.theforthbridges.org/about-the-forth-bridges/forth-road-bridge/forth-road-bridge-history/

[19] Falkirk Herald, 24 July 1946.

[20] “The cycle traffic on the Wolverton Road [near Stoney Stratford in Buckinghamshire] represents in numbers 54 percent of the traffic on the road throughout the day. At rush hours it reaches 80 percent of the total traffic using the road … At Magdalen Bridge in Oxford, 12,500 cyclists pass in the sixteen hours of the normal census day. They represent in numbers 50 percent of the total traffic. At a point in Bedford cyclists represent in numbers 80 percent of the total daily traffic …

Taking the Division as a whole, pedal cyclists represent in numbers on the Class I roads 22 percent of the total number of vehicles and on the Class II roads 43 percent …”

“Cycle tracks and Dual Carriageways, ”To the chief engineer, Divisional Road Engineer, Eastern Division, May 2, 1935

[21] “At many points along all the main streets and roads Committee members and many assistant workers have stood for hours taking a census of cycles and motor vehicles. The difficulty can be gauged by the fact that for ten minutes in one midday period cyclists passed the census-takers at the rate to three thousand an hour.” See: “Council of Social Service’s Town Planning Survey,” Bedfordshire Times and Independent, January 5, 1945.

[22] Bedfordshire Times and Independent, 23 September 1949.

[23] These were:

- Track alongside the then Bedford Town Football Ground in Queens Park, now known as The Slipe

- Track alongside Longholme Way

- Track linking Elstow Road and Ampthill Road

- Track linking Willow Road and Pearcy Road.

There were further improvements to Bedford’s cycle “network” in the 1960s, and then there was a slightly more ambitious expansion in the 1970s. Not that this was welcomed by all. “Don’t waste cash on racetrack, say angry residents,” screamed a 1977 headline in the Bedfordshire Times.

This was in response to plans put forward in the Bedford Urban Transportation Study of 1976. Bedford’s council planned to install a number of striped, protected, and off-carriageway routes from suburban areas into town, mostly away from arterial roads. Two reasonably good routes were installed, but the rest were spiked because of protests from residents.

Bedford’s assistant engineer – and the engineer responsible for cycling – throughout much of the 1970s was Peter Snelson, one of the authors of Bicycle Planning by Architectural Press of London.

www.cyclebedford.org.uk/Bedford_CycleHistory.pdf

[24] https://www.halasandbatchelor.co.uk/history

[25] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ta_n1wLARKM&t=5s

[26] According to Tim Jones, an academic expert – Tim Jones is a Research Fellow at Oxford Brookes University.

[27] … provided with their own segregated junction – Tim Jones, The Role of National Cycle Network Traffic-Free Paths in Creating a Cycling Culture, Oxford Brookes University, unpublished thesis, 2008.

[28] The Hidden Stevenage, Eric Claxton, Book Guild, Lewes, 1992.

[29] Construction of the cycleway network was given – Stevenage Master Plan, 1966; see: http://www.idoxplc.com/idox/athens/ntr/ntr/cd2/html/txt/r58h0700.htm .

[30] By 1964 cycle use was down to thirteen percent – Stephen Ward, Peaceful Path: Building Garden Cities and New Towns (Hatfield, UK: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2016).

[31] Claxton was chief engineer of Stevenage for the ten years – Eric Claxton, The Hidden Stevenage, The Creation of the Substructure of Britain’s First New Town (Leicester, UK: The Book Guild, 1992). Claxton has also written a number of articles about Stevenage.

See also: “Designing a new town for cyclists and pedestrians,” paper presented to International Federation of Pedestrians, 1973; “Designing for pedestrians and cyclists”, paper presented to the Institute of Civil Engineers’ Conference, November 1975, and reported in the Proceedings, Thomas Telford Ltd., London, 1976; “The cost of crossing the road contrasted with the price paid by the community,” paper presented to the International Federation of Pedestrians, Geiolo, Norway, 1976.

[32] Claxton complained that he had provided – Eric Claxton, The Hidden Stevenage, The Creation of the Substructure of Britain’s First New Town, (Leicester, UK: The Book Guild, 1992).

[33] Dr. Alex Moulton, designer of the eponymous bicycle – Alex Moulton, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, January 1968.

[34] Mr. Claxton was a keen cyclist – Eric Claxton, The Hidden Stevenage, The Creation of the Substructure of Britain’s First New Town (Leicester, UK: The Book Guild, 1992).

[35] “I did them for people – Richard North, “Transport for the Future,” Vole, December 1977. Vole was a British environmentalist magazine published between 1977 and 1980. It was a cross between The Ecologist and Private Eye, and shared many of the same contributors and cartoonists. It was seed-funded by Monty Python’s Terry Jones.

[36] CTC wanted nothing to do with cycle tracks – Eric Claxton, The Hidden Stevenage, The Creation of the Substructure of Britain’s First New Town (Leicester, UK: The Book Guild, 1992).

[37] ** “However, organised cycling changed –** Eric Claxton, “Design for Pedestrians and Cyclists,” Paper 12. Transport for Society, Institution of Civil Engineers, 1975.

[38] British local authorities asked Claxton to evaluate – “Home of the Bike,” 1974 report commissioned by the Nottingham Corporation, predecessor of Nottingham City Council, and Raleigh Industries Ltd., Nottingham, Nottingham City Corporation and Raleigh Industries Ltd., Nottingham. See also: Eric Claxton, “Cycleways of Stevenage & Cycleways of Portsmouth,” Urban Traffic Research Report, Special Edition, Vol. 9: Report on the 1980 Velo City Conference, Bremen Federal German Traffic Ministry, 1981.

[39] Lancashire Evening Post, 23 January 1956

[40] Roads in England and Wales by Great Britain. Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, 1958.

[41] Nottingham Journal, 27 April 1939.

[42] https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15&lat=53.05239&lon=-1.06243&layers=193&b=3

[43] https://maps.app.goo.gl/Za7A7YtXbZ334RfF6

[44] Roads in England and Wales by Great Britain. Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, 1958

[45] https://goo.gl/maps/8TYSzYr1HGF2

[46] Western Mail, 8 December 1937.

[47] https://goo.gl/maps/8TYSzYr1HGF2

[48] https://maps.app.goo.gl/ui2fe4imBU2xGmKQA

[49] Reading Mercury, 23 August 1958.

[50] https://picturenottingham.co.uk/image-library/image-details/poster/ntgm006790/posterid/ntgm006790.html

[51] https://www.icevirtuallibrary.com/doi/pdf/10.1680/iicep.1967.8430

[52] Belfast News-Lette, 17 December 1936.

[53] Scheme & Estimate for proposed Belfast-Holywood By-pass Road, Ministry of Home Affairs, Stormont, December 1936. By R. D. Duncan. Thanks to Wesley Johnston for the information.

[54] https://goo.gl/maps/gSFj7vkPUGE2

[55] Belfast Telegraph, 27 October 1950.

[56] https://www.readtheplaque.com/plaque/opening-plaque-the-sydenham-bypass-belfast

[57] Belfast Telegraph, 21 November 1959

[58] Belfast Telegraph, 27 November 1976.

[59] Belfast Telegraph, 23 September 1977.

[60] https://www.google.co.uk/maps/@54.6184065,-5.8614518,221m/data=!3m1!1e3

[61] http://www.wesleyjohnston.com/roads/a2sydenhamholywoodbypass.html

[62] https://goo.gl/maps/Kte8Ssc2frFt1Pio9 & https://maps.nls.uk/view/189234621 & https://m.facebook.com/STOURPORTPAST/photos/a.163681577017370/1596892600362920/?type=3&source=57&tn=EH-R

[63] Birmingham Daily Gazette, 28 May 1936.

[64] https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/7368853