DISUSE AND DISREPAIR

The 1930s cycle tracks might have been initially well used by ordinary cyclists, but from 1949 to 1972, the number of people riding bicycles fell off the proverbial cliff. And with the steep fall in cyclists, there was a knock-on reduced demand for the period cycle tracks. In short, they failed.

Even the best cycle tracks began to ossify, and with a reduction in use came a decrease in maintenance, a vicious circle of neglect. Some tracks were all but abandoned just twenty years after their installation; dirt accumulated, grass grew over the detritus, and some of the innovative-for-the-time cycle tracks disappeared from view and then from memory. Other tracks remained in full view, unused, hidden in plain sight.

Infrastructure needs use, and while cycling’s overall decline didn’t cause the failure of the 1930s cycle track programme, it certainly didn’t help. The fall — partly caused by the rise of motoring — bears further examination, especially considering the significant growth in cycling in the mid-1930s when cyclists doubled in numbers in just five years and, for a short time, became the majority road users in the UK.

Working-class transportation cycling dropped precipitously in the 1950s. People were desperate to drive rather than cycle. Riding a bike was seen as a tell-tale sign of poverty of aspiration and means. Bicycles and cloth caps were — literally and figuratively — thrown on the scrap heap. By the 1960s, a Raleigh worker would arrive at work not on a bicycle but in a car. New cars would have been out of the reach of most blue-collar workers at the time, but there was a roaring secondhand market, and buying in instalments on the “never-never” became socially acceptable.

| YEAR | SALES | OTHER INFO |

|---|---|---|

| 1935 | 1,600,000 | |

| 1936 | 1,480,000 | |

| 1937 | 919,000 | |

| 1938 | 1,170,000 | |

| 1939 | 885,000 | |

| 1940 | 503,000 | |

| 1941 | 355,000 | Raleigh and other cycle firms making armaments, not bicycles |

| 1942 | 556,000 | |

| 1943 | 547,000 | |

| 1944 | 446,000 | |

| 1945 | 383,000 | |

| 1946 | 1,030,000 | Immediate tripling in sales following end of WWII |

| 1947 | 1,040,000 | |

| 1948 | 1,130,000 | |

| 1949 | 1,400,000 | |

| 1950 | 1,290,000 | |

| 1951 | 1,290,000 | |

| 1952 | 835,000 | |

| 1953 | 1,000,000 | |

| 1954 | 1,200,000 | |

| 1955 | 1,210,000 | |

| 1956 | 867,000 | Huge drop in sales with no recovery for 20 years |

| 1957 | 998,000 | |

| 1958 | 831,000 | |

| 1959 | 952,000 | |

| 1960 | 809,279 | |

| 1961 | 665,635 | |

| 1962 | 623,594 | |

| 1963 | 575,552 | |

| 1964 | 703,766 | |

| 1965 | 727,951 | |

| 1966 | 673,092 | |

| 1967 | 674,377 | |

| 1968 | 624,377 | |

| 1969 | 545,952 | Lowest post-war sales; launch of Raleigh Chopper |

| 1970 | 552,299 | |

| 1971 | 620,652 | |

| 1972 | 694,274 | |

| — | — | — |

| 1980 | 1,600,000 | |

| 1984 | 2,000,000 | Sales doubled over 10 ten years; peak of 80s BMX boom |

| 1985 | 1,500,000 | BMX boom over |

| 1986 | 1,560,000 | |

| 1987 | 2,200,000 | Mountain bike boom |

| YEAR | SALES | OTHER INFO |

Some of this 1930s infrastructure could be dug up or otherwise resurrected — one of the aims of this project — but many of the period cycle tracks were white elephants when built and remain so today.

Even the best of them were flawed.

“The 1930s cycleways on Euxton Lane suffer from three principal problems that are generic for all the cycleways built in that era: they give up at junctions, even those with minor side streets; they do not themselves connect important origins/destinations; and they terminate abruptly without connecting to a wider cycling network of a similar standard,” states John Dales of Urban Movement who evaluated twelve period cycle tracks in 2022.

These problems were evident to many in the period. Writing to the Manchester Evening News in 1949 a cyclist listed four disadvantages of cycle tracks.

First, “they are unsafe because there is no indication in which direction a single track may be used.” Second, “they are used by pedestrians proceeding in both directions and quite often as a pram track.” Third, “where tracks are crossed by side roads, motorists frequently ignore the cycle tracks.” And fourth, “there are the very dangerous places where one must leave the track to get back on the roadway.”

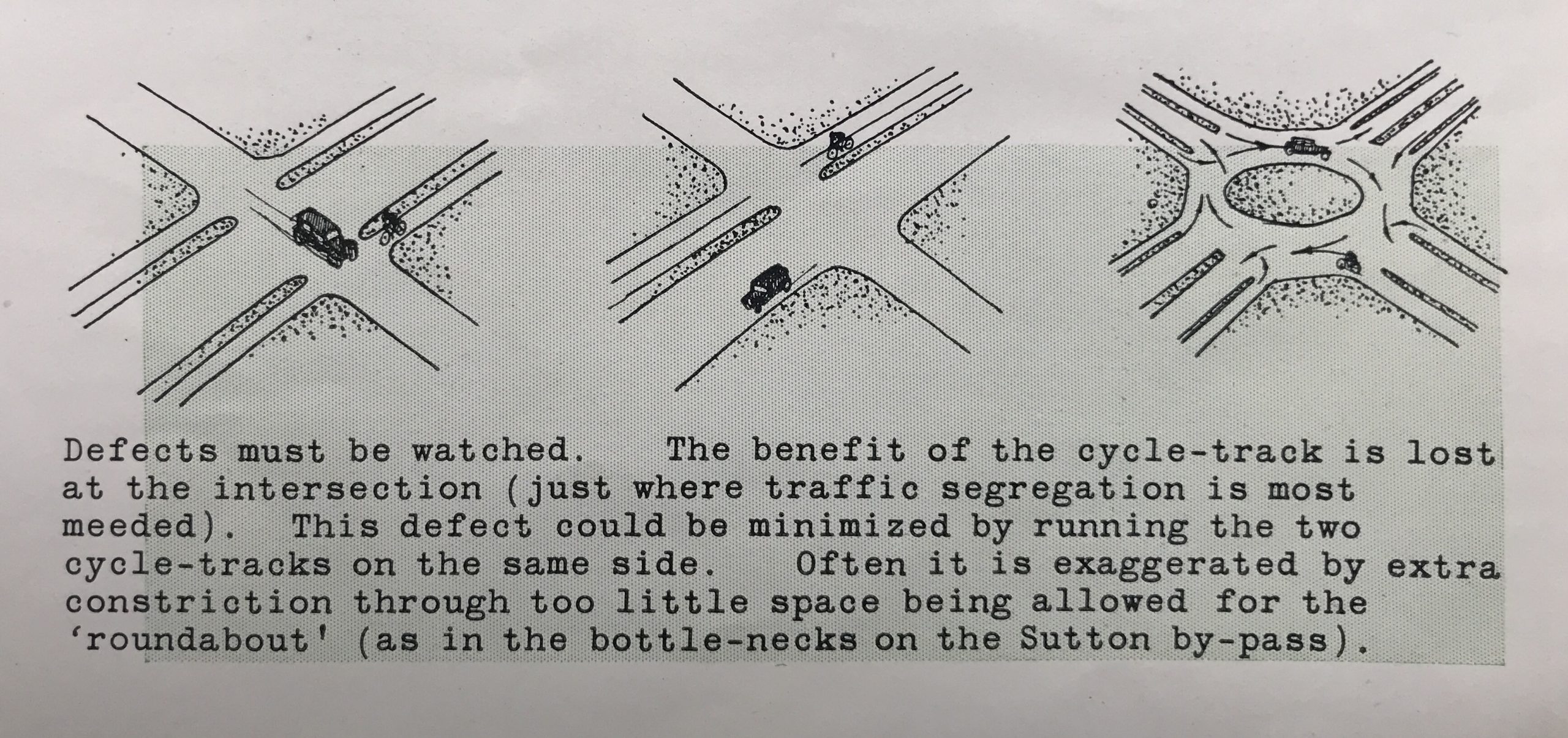

The giving-up-at-junctions flaw was a key obstacle to greater use, and the flaw was frequently pointed out at the time. A 1937 illustration in the Architectural Review showed three intersections with cycle tracks. One of the intersections portrayed an unprotected crossroads with cycle tracks on each side of the road — a motorist was shown speeding towards a cyclist on one of the cycle tracks. “The benefit of the cycle-track is lost at the intersection, just where traffic segregation is most needed,” intoned the illustration’s caption. “This defect could be minimized by running the two cycle-tracks on the same side,” suggested the caption, with the illustration featuring a double-sided cycle track to one side of an unprotected junction. The third and final illustration featured a roundabout in the centre of four roads protected with cycle tracks. A cyclist turning left would be protected by the kerb of an adjoining cycle track although a cyclist going straight ahead or turning right would still have to mix with motor traffic.

The third treatment showed a junction that could have evolved into a modern Dutch-style protective roundabout.

In 1938, the Automobile Association (AA) recommended Dutch-style cycle underpasses. The AA’s deputy secretary, Edward Fryer, told the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents, more commonly known as the Alness Committee, that “the [cyclist] would pass under the carriage-way, come up on to the bank and join the other cycle track which goes continuously along the arterial road.”

Cycle track “defects” were also evident to those who designed them. As recounted elsewhere in this study, Eric Claxton, the designer of Stevenage’s 1950s cycleways, was a junior engineer in the Ministry of Transport in the 1930s and, in the 1970s, he wrote that the cycle tracks he worked on in London were substandard. “As a cyclist, they gave me no satisfaction,” he complained, adding that they:

… were too narrow. They were made of concrete and suffered from either cracking or construction joints. They provided protection where the carriageway was safe but discharged the cyclists into the maelstrom of main traffic where the system was most dangerous.

It wasn’t just junior engineers who knew the design of the cycle tracks wasn’t up to scratch. Sir William Brass, the Tory MP for Clitheroe, pointed out a fundamental flaw in a parliamentary question to the minister of transport in 1938. He suggested that the MoT should “make sure that these cycle tracks go straight across at cross roads, instead of going down on to the main road as they do at present.”

A Ministry of Transport report in 1944 stated that the opposition of some cyclists to cycle tracks was understandable and “does not arise from a spirit of obstinacy but is largely based on the inadequacy of the cycle tracks so far constructed and the dangers [to] which they give rise.”

“Even where the tracks are in good repair they present a number of hazards,” pointed out a parliamentary cycling safety report in 1956, including “unsatisfactory features” such as “they normally break off at junctions, which are the very points at which cyclists need protection, and, particularly in ‘built-up’ areas they are used by pedestrians, intersected by driveways to houses and blocked by parked vehicles.”

That cycle tracks needed protection at junctions was understood at the highest levels.

“Cycle paths provided in future should meet all cyclists’ objections,” promised Noel Baker, parliamentary secretary, Ministry of War Transport, speaking to the Pedal Club in 1944.

“We hope that at the more important road junctions,” added Baker, “we shall have two-level roundabouts by which cyclists and pedestrians will each have their own means of passing in complete safety, wholly segregated from the motor traffic on the road.”

Such a grade-separated roundabout was built. But not in the UK. It was built in Utrecht in the Netherlands, between 1941 and 1944. Designed in 1936, the Berekuil — or “bear pit” — roundabout is still used today.

Manchester’s Town Plan of 1945 featured separated cycle tracks. Roads, the plan imagined, would be “slightly elevated” and “cyclists and pedestrians [will be able to] cross under the junction in separate subways.”

Design & Layout of Roads in Built-up Areas, a government style-guide issued by the Ministry of War Transport in 1946, also recommended protection for cyclists at junctions. A technical drawing showed how cycle tracks should be carried around roundabouts, offering protection all the way around.

Produced by a team led by Sir Frederick C. Cook, Design & Layout of Roads in Built-up Areas stated that “objections to cycle tracks have been stimulated by the indifferent surfaces with which some of the early tracks were laid,” and the tracks didn’t allow for an uninterrupted ride, a defect that had to be remedied.

The report advised that “the profile of tracks should be unbroken across intersecting vehicular entrances, and they should approach side roads with an easy ramp.”

Design & Layout of Roads in Built-up Areas was a fleshed-out version of various Memorandums issued by the Ministry of Transport; the first had been issued in 1930, followed by a revised edition in 1937 and the further revised Memorandum No. 575 of 1943. This called for “Cycle tracks, footpaths, and suitable crossings for pedestrians” beside the new “arterial” roads and bypasses then being constructed.

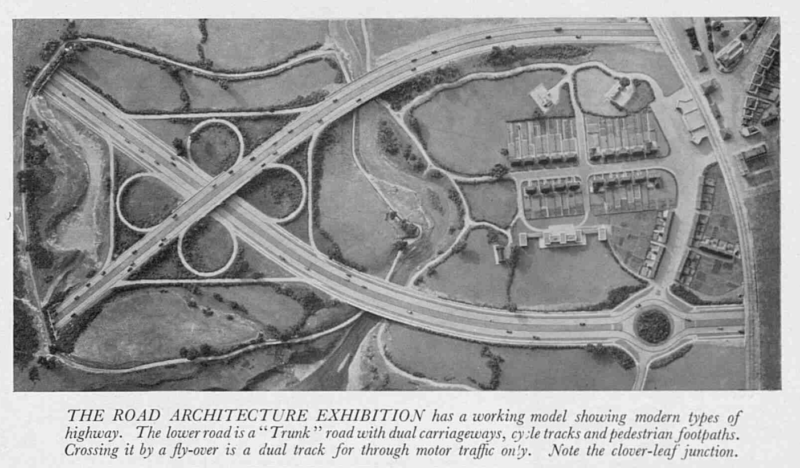

In 1948, the Ministry of Transport commissioned large-scale models of how it proposed the roads of the future would look and displayed them for lawmakers in the Houses of Parliament. One of these models featured an “all-purpose road” with a roundabout junction with three flyover bridges. Two of these bridges were to carry motor traffic; the third, in the middle, was for pedestrians and cyclists to enable “the free and safe passage of motor traffic.”

Britain’s road-building programme was cancelled at the end of WWII, and when it was resurrected at the end of the 1950s, there was no impetus to include cycle tracks, never mind improving them. Those built in the 1930s and early 1940s fell into disuse and disrepair.

NOTES

[1] Brits cycled 14.2 billion miles in 1952. This dropped to 7.5 billion miles by 1960, and was 3.4 billion miles by 1967. It is roughly 3.2 billion miles today, and has been about that since 2009. (See: “Pedal cycle traffic (vehicle miles / kilometres) by vehicle type in Great Britain, annual from 1949,” Department for Transport statistics, http://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-transport/series/road-traffic-statistics .) These are average stats for the whole of the UK. There were pockets of high cycle usage, and not just in places such as Cambridge but also Hull, York, March and others. Even as late as the 1968 census cycling usage remained remarkably high in those towns.

“Cycling levels have shown long-term decline since the 50s. Between 1952 and 1970 annual distance cycled fell from 23 billion kilometres (13% modal share) to 5 billion kilometres (1% modal share),” See: *Urban Transport Analysis,” Cabinet Office Strategy Unit, 2009.

Cycling levels fell off the proverbial cliff in 1949, and this has been tracked in oral history and diary research, too. Colin Pooley and Jean Turnbull interviewed or analysed the writings of thousands of Brits, tracking their use of getting to work. By the mid-1930s “approximately one fifth of men cycled to work, and around one tenth of women.” (See: Pooley, C., and J. Turnbull, “Modal choice and modal change: The journey to work in Britain since 1890,” *Journal of Transport Geography*, 2000.)

[2] H. Downs. 20, Beresford Road Stretford. *Manchester Evening News*, 21 January 1949.

[3] Report by the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents (session 1938-39). https://archive.org/details/b32170312

[4] Eric Charles Claxton, The Hidden Stevenage: The Creation of the Substructure of Britain’s First New Town, Remembered, Book Guild, 1992.

[5] HC Deb 14 March 1938 vol 333 c29 29

[6] *Interim Report of the Committee on Road Safety*, Ministry of War Transport, H.M.S.O., 1944.

[7] Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, Committee on Road Safety, Report on child cyclists, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1956. https://archive.org/details/op1265790-1001

[8] Baker wasn’t lying (he was a Quaker, after all) but his promise was not kept. Cycle tracks built in the 1930s were not continued in the 1940s. Fun fact: Baker is the only person to have won an Olympic medal and received a Nobel Prize. He won a silver medal for the 1500m at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1959.

[9] *Yorkshire Evening Post*, 14 March 1944.

[10] http://www.usine-utrecht.nl/rijkswegenplan-1936-verkeersplein-berekuil-waterlinieweg/

[11] https://issuu.com/cyberbadger/docs/city_of_manchester_plan_1945