HIDDEN HISTORY: BRITAIN’s 1930s DUTCH-INSPIRED CYCLE TRACKS

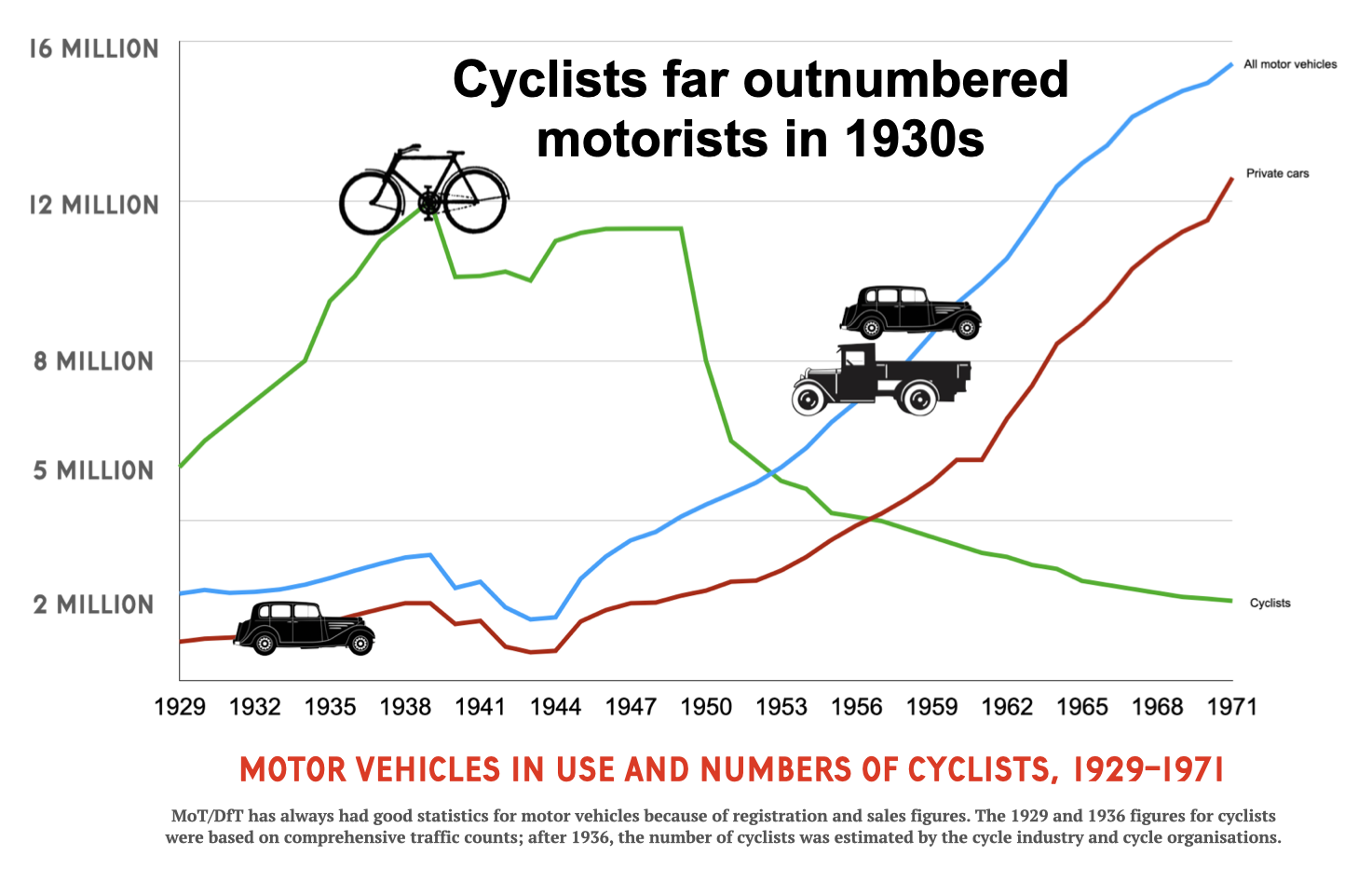

In the 1930s, Britain had the makings of a Dutch-inspired protected cycle network. One hundred or so “cycle tracks” were constructed, ostensibly for road safety, with cash and design input from the Ministry of Transport (MoT). Fearing a reduction in amenity, cycling organisations campaigned against the tracks, but ordinary cyclists used them. Working-class transportation cycling had exploded in the mid-1930s, with eight million more cyclists than motorists at the time. However, between 1949 and 1972, cycle use collapsed, and the MoT’s 190-mile track network fell into disuse and gradually faded from memory. Today, some of the innovative-for-the-time state-led infrastructure could be brought up to modern standards. Space for cycling that many planners and politicians say isn’t there is there, and – in short stretches — has been there for more than 85 years.

Some of the cycle tracks are long gone, subsumed by later road widening; many still exist, covered by grass or are wrongly thought to be service roads for motorists. Most of them are hidden in plain sight, with few people — or local authorities — realising the infrastructure is quite so old or meant for the use of cyclists.

With original concrete surfacing and kerbs the half-mile-long cycle tracks on both sides of Durham Road in Sunderland are among the best preserved in the country. Yet, the infrastructure is ignored. Cyclists are often observed using the adjoining period footway rather than the cycle track, which appears to be perceived as a service road for motorists yet offers no such functionality. The cycle tracks are, therefore, almost wholly unused yet remain in place, the protective kerbing redundant.

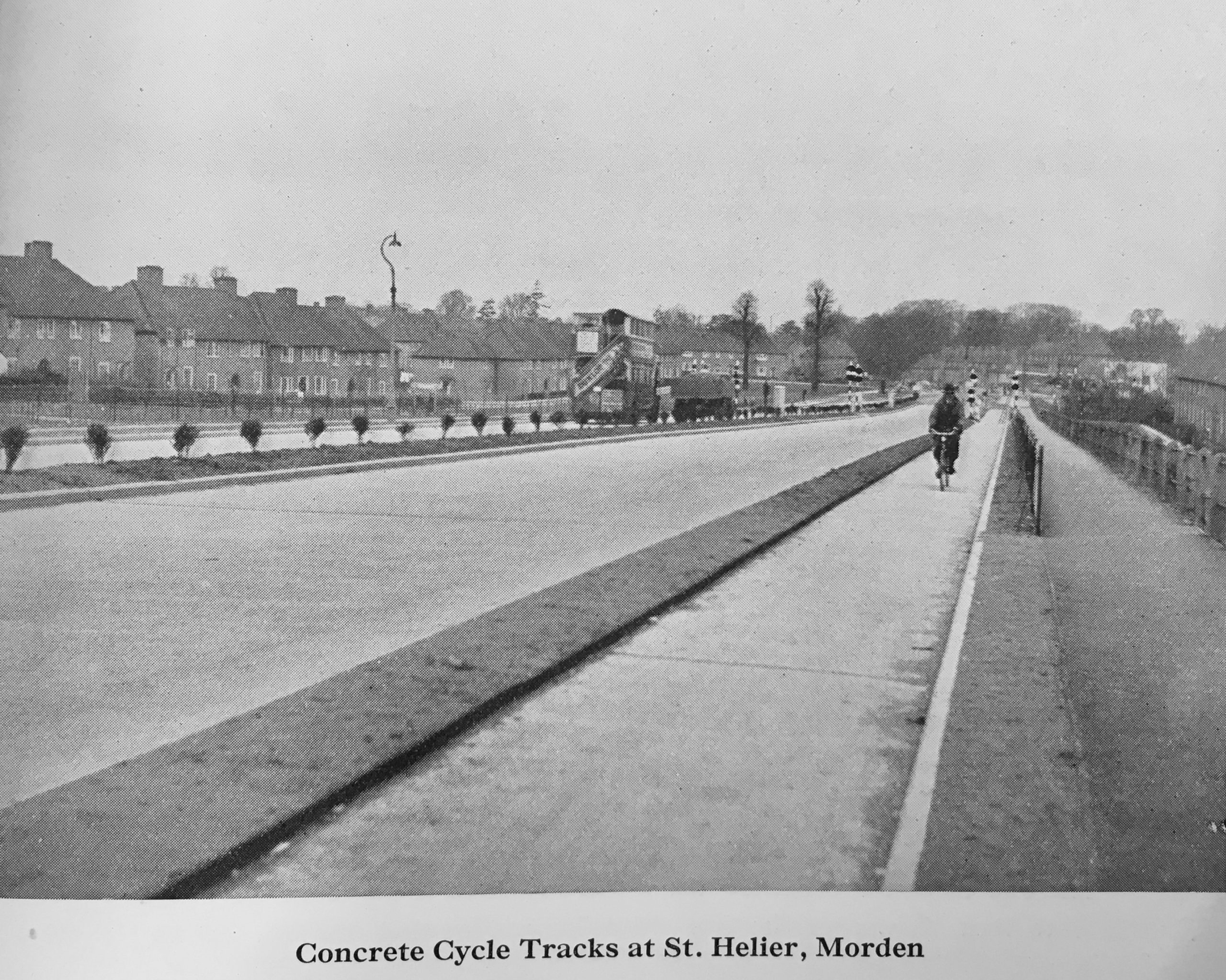

From 1934 until a little after the outbreak of WWII, the MoT grant-aided the creation of these kerb-protected tracks. Many of them were 9-ft-wide. A small number were even wider. They were modelled on Dutch protected cycle infrastructure of the same period.

Some 500 miles of these cycle tracks were planned, according to contemporary press reports and internally distributed MoT documentation. This study has identified at least 102 separate cycle tracks around the UK in varying degrees of preservation.

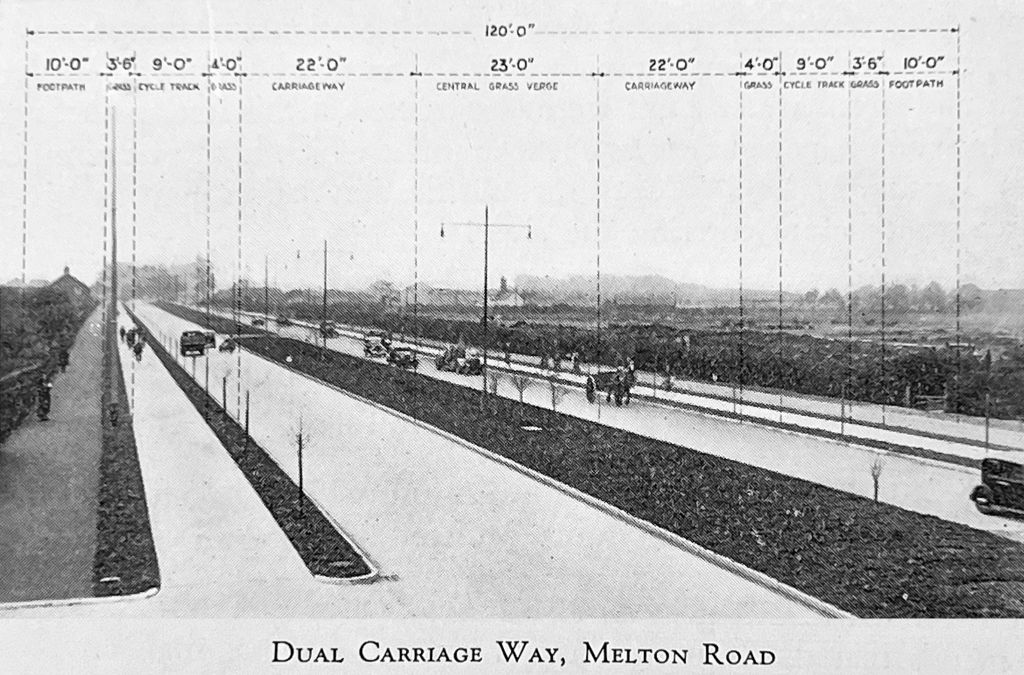

Some of the cycle tracks were “rediscovered” using Google Street View, and others were surmised from local authority archive searches. In 2022, using the findings of this study and Department for Transport-funded design work, Leicester City Council was awarded £2.2 million to refurbish a 1930s cycle track beside Melton Road on the city’s outskirts.

FIRST TRACK

Britain’s first protected cycle track was built – rapidly and shoddily – in London in 1934. The two-and-a-quarter-mile stretch of uneven concrete from Hangar Lane to Greenford Road in Ealing was retrofitted to the new arterial Western Avenue. The track was commissioned by Colonel Bressey, the MoT’s chief engineer working to a brief from the Minister of Transport Oliver Stanley. (Today, this role is known as the Secretary of State for Transport, or Transport Secretary.)

On 8th February 1934, Stanley told parliament he would ask the MoT to experiment with “cycling tracks along the side roads.”

The following day, Colonel Bressey wrote to the MoT’s divisional road engineer for London asking him to “take an early opportunity of discussing with the County Surveyors of Surrey and Essex the best location that could be selected for an experimental length of cycle track adjoining an important exit from London.”

“In considering the selection of a route you would doubtless have regard to the census returns showing the proportion of pedal cyclists using particular routes,” continued Bressey.

“Mr. Winfield, the County Surveyor of Bucks … suggested that cyclists were found in greatest numbers in the neighbourhood of factory groups (such as the Slough Trading Company), where the workers at morning, noon and night travelled in large numbers on their cycles between the work and their homes.”

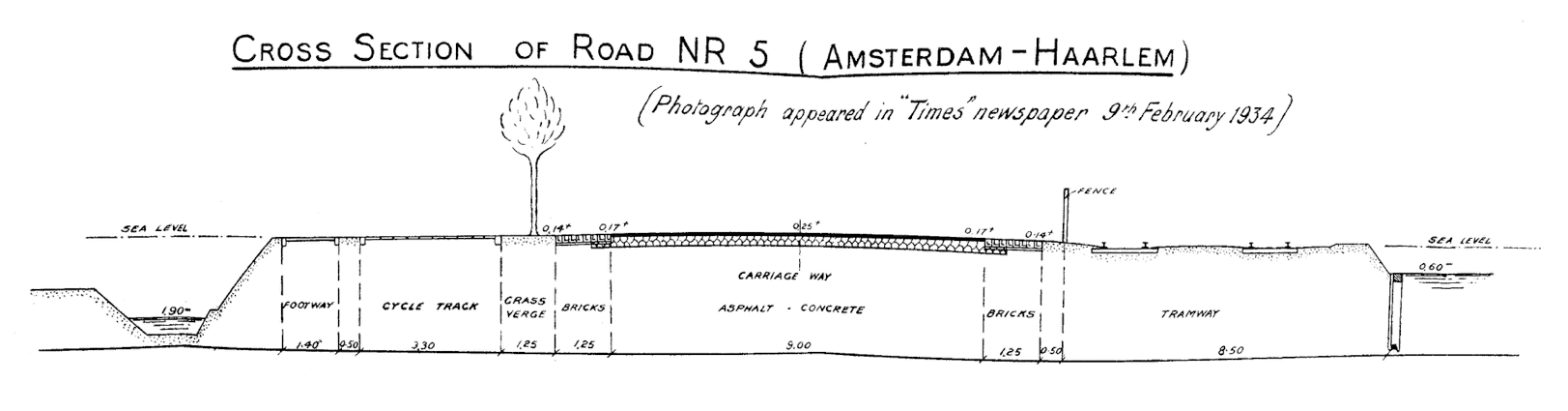

Bressey sought advice from his Dutch counterpart following a note from transport minister Stanley, who was much taken with a photograph of a Dutch cycle track, published in The Times on 9th February. Bressey contacted the Dutch infrastructure ministry director W.G.C. Gelinck on 14th February to ask him about the photograph and the wide cycle tracks built beside several new arterial roads in the Netherlands.

“As you are probably aware,” Bressey wrote to Gelinck, the “cycle track … has never gained favour in Great Britain, but my Minister is now devoting some attention to the subject, in the hope that the death toll on our roads might be lessened if a special provision were made for pedal cyclists, among whom, unfortunately, the mortality is very high proportionately at the present time, as compared with other road users.”

Bressey added, “We shall shortly try the experiment of forming a cycle track along one of the busiest outlets from London, and I am accordingly anxious to collect the most recent particulars as to the dimensions and form of construction adopted elsewhere.”

On 13th March, Gelinck’s reply informed Bressey that the photo published in The Times showed “Government Road No. 4 leading from Amsterdam to Haarlem. The road was asphalt, cycle tracks in both directions of 3.3m (10.83ft) wide of cement tiles.”

He also supplied plans, maps, and other advice, all in English.

With these plans, Bressey commissioned Britain’s first cycle track for Western Avenue, a relatively new arterial road.

Called a “new departure in traffic control” by the Daily Mirror the tracks were built swiftly and open for use less than two months later.

A brochure produced for the official opening on 14th December of that year puffed: “For workers traveling between their homes and the factory, for children proceeding to and from school, for holiday-makers intent on a country jaunt, these tracks should prove a boon and a safeguard.”

A British Pathé cinema news voiceover said the Western Avenue cycle track was a “new safety innovation” and that “motorist users of the road will be appreciative of this new boon.”

A small crowd witnessed Hore-Belisha cutting the ribbon, officially opening the experimental cycle track. He said the track was for the “comfort and safety” of cyclists.

“The first to ride over the cycle track was Oliver Dietrich who, wearing leggings and a top hat, was mounted on a 50-year-old penny-farthing bicycle,” recorded The Times.

Hore-Belisha, speaking at a luncheon at Wembley Stadium after the ceremony, said that the “two cycling tracks which had been provided gave effect for the first time to the principle that classes of traffic should be segregated in accordance with the speed at which they could travel,” reported The Times.

The original 8ft 6in cycle tracks, both sides of Western Avenue, were, according to The Scotsman, divided thus:

“Two one-way roads separated by a verge. Two one-way cycling tracks of white concrete. Two pedestrian paths.”

The newspaper added: “The cyclists’ tracks are to be placed on what would normally be the grass verge at the side of the highway. They will be separated from the kerb by a sloping path of macadam, the dark colour of which will warn them at night that they must not wander towards the road.”

Cycling organisations opposed the new cycling track, and many club cyclists refused to ride on it.

While the first cycle track was shoddy, most subsequent ones built over the next six or seven years were higher quality. One in Manchester was made with pink concrete; the cycle tracks beside the Formby bypass were capped with green asphalt.

Back in March, E. Butterworth of the Rochdale section of the National Clarion Cycling Club had written to Hore-Belisha protesting “against the Ministry of Transport using public money to make experimental cycle paths, as we cyclists object to special paths and do not think them a safety first measure.”

Britain’s other cycling organisations — including the Cyclists’ Touring Club (CTC), which is today’s Cycling UK, and the National Cyclists’ Union (NCU), the forerunner of today’s British Cycling — were also opposed to any cycle tracks, fearing cyclists would be corralled on infrastructure they felt would be narrow and bumpy and which, in time, would become compulsory for cyclists to use, reducing the space for group cycling.

Nevertheless, the MoT pushed on, and over the next several years, the British government would only provide maximum road-building grants to local authorities if they included cycle tracks in their plans.

In some cities, the class-focussed cycle tracks were built on social housing estates leading to munitions and aircraft factories as part of the war effort. (Workers were expected to cycle to work; managers to drive.)

Most of the cycle tracks were two to four miles long, although the one from Romford to Southend was more than fifteen miles long. The tracks were generally constructed on both sides of the many new “dual carriageway” roads built in a feverish rush during the 1930s and 1940s or, more rarely, retrofitted to arterial roads constructed in the 1920s.

Local authorities appear to have constructed more tracks than are noted in the official national record, including stats given as parliamentary answers by transport ministers of the day. Even those cyclists who campaigned against the track programme didn’t know the full extent of the network they opposed.

Transport ministers — there were several in this period — crowed that many miles of cycle tracks would be constructed by the mid-1940s and that once a sufficient length had been installed then compulsion would likely follow.

“If it were possible to provide facilities that are equal to those that we enjoy now, with the additional advantage that they would not be shared by motorists, I think that cyclists would have no objection … If the paths are by any miracle to be made of such width and quality as to be equal to our present road system, it would not be necessary to pass any laws to compel cyclists to use them; the cyclists would use them.”

G.H. Stancer, secretary, cyclists’ touring club, 1938

Several of the planned schemes were cancelled soon after the outbreak of war. However, this study estimates that at least 190 miles of cycle tracks existed by the 1950s, spread over 102 separate schemes. Nearly 140 other road schemes mentioned in period newspapers as soon to be built with cycle tracks have been ruled out as either unbuilt or unproven.

Did the MoT count the mileage of both sides of a road’s cycle tracks to reach its proposed total of 500 miles? Period sources say not, and this research project uses road length instead of adding the mileage of both sides.

The tracks are now in varying degrees of preservation. Some are still in use; a few have been “lost,” others are not today understood to be cycle infrastructure and — like the cycle tracks of the St. Helier Estate in London or Lostock Road in Urmston, Manchester — they are used instead for the residential parking of cars.

Some of the better 1930s cycle tracks — historic transport assets — could be rededicated to everyday use. Others are buried under soil and turf and could be excavated. Many have lasted this long only out of sheer luck; some could be “listed” so that their kerbing cannot be removed to widen roads for motor traffic; others could be improved by being resurfaced and properly signed as has happened in Leicester and as part of the Great North Cycleway at Neville’s Cross, Durham, on what used to the A1 Great North Road.

FROM CYCLE TRACK TO CYCLEWAY

The construction of these period cycle tracks is an excellent example of state-led innovation, with the MoT playing a pivotal role in aiming to increase cyclists’ safety through engineering long before the modern call to “go Dutch.” Another impetus was the officially unvoiced desire to rid the roads of slower road users. Cycling was considered an anachronism by many period motorists, who were annoyed and perplexed that cyclists had doubled in number in the mid-1930s and far outnumbered cars on the roads.

Apart from the first track, built shoddily in 1934 on Western Avenue, most of the tracks were built to a high quality. The cycle track near Longniddry in Scotland was constructed as an MoT experiment to evaluate the best surfaces for what, within ten years, was planned to be an extensive national network of cycle tracks.

Several of the schemes — such as Kidlington, Oxfordshire, probably built in 1950; the short length of cycle tracks and tunnel at Heathrow, built in 1955; and the Longton bypass in Lancashire, finally constructed in 1957 — are post-war, but they were built to the dictats laid down in the 1930s design guide. For this reason they have been included in this study. Post-war cycle tracks built to similar designs as Dutch cycle infrastructure of the 1950s and 1960s — such as the “cycleways” of Stevenage and networks in other New Towns — are not part of this research project.

Even though cycling organisation officials decried the “Leper ways” for supposedly curtailing cyclists’ hard-won freedom to the King’s highway, period sources and traffic census data attest that everyday cyclists often made good use of the new tracks. Nevertheless, most of the 1930s-era cycle tracks fell out of use within ten years, partly because of the post-war collapse in cycle use, dropping by 84 percent in just over 20 years. Cycling went from a 25 percent modal share in 1949 — today’s Dutch level of use — to just over 1 percent in 1972.

PUBLIC POLICY

This study reconstructs the history of Dutch-inspired cycle tracks built by the British government in the 1930s through the examination of Ministry of Transport archives, press releases, newspaper articles, newsreels, public information films, local authority records, and other materials, including lavish brochures celebrating the civic ribbon cuttings at the opening of dual-carriageways and bypasses.

“Separating” cyclists from the increasingly heavy and fast motor traffic of the day during this period — ostensibly for safety reasons but also to smooth the way for unhindered motoring — was primarily the desire of non-cyclists and was the subject of public controversy.

Policymakers sought to monitor the anxieties from cycling organisations against seperation, but the response was largely dismissive, with the rights and desires of motorists — then a minority on the roads — given precedence.

The so-called “roads lobby” was a growing force in the 1920s and 1930s, competing with the rail lobby, which continued to hold more sway in government until after WWII. Many MPs (and others in positions of power and influence) were pioneer motorists, and most had long since ceased being cyclists.

Cyclists – part of the elite in the Victorian period – were largely proletarian by the 1930s, and a massive increase in early- to mid-1930s cycle use took government ministers and officials by great surprise. Many were horrified by the doubling of cycle use, fearing the utility of elite-led motoring would be decreased.

While road safety was always given as the primary motivation for the cycle track programme this study demonstrates that many organisations, influential individuals, and officialdom in general also wanted to corral cyclists in order to make more space for motorists in the full knowledge that this would make cycling less attractive.

MIGHT IS RIGHT

The increase in cycle use in the mid-1930s led to an unmissable uptick in cyclist fatalities. Concern about the rising number of cyclist deaths came in lockstep with the increasing acceptance of the significant role of the car in British society. British law had only lightly intervened in the power struggle between car drivers and other road users for the first two decades of the car’s existence. (Privately owned cars were essentially the privilege of the elite until the 1920s; professional drivers — of trucks and omnibuses — were working class.) The road was the “king’s highway,” and no person, whether on foot, on two wheels, or in a motor vehicle, was allowed to either obstruct it or be denied access to it. As car ownership became increasingly middle-class at the end of the 1920s and into the 1930s, the motorist’s assumed role as “king of the road” was increasingly voiced and became socially acceptable.

The young discipline of British motoring law — including the rights of where certain classes of road users could and could not go and could and could not do — sought only weakly to reconcile the competing aims of different interest groups. By and large, the rights of motorists were solidifying into majority rights, with all other road users perceived to have fewer and lesser rights.

In response to public fears about the coercion of motorists, pedestrians, or cyclists, British governments had hitherto appealed to common sense and civic duty rather than the threat of punishment or the exertion of control. Despite much pressure to do so, Britain did not enact Dutch- and German-style laws to compel cyclists to use cycle tracks just as there are no US-style laws against the faux crime of “jaywalking,” a misdemeanour largely invented by “ motordom,” shows American academic Peter Norton.

Unlike in Nazi Germany, Britain’s officialdom — politicians, that is, and civil servants, including road traffic engineers at the only recently formed Ministry of Transport (founded in 1919) — did not openly discriminate against cyclists. Letters to the Ministry from motorists in the 1920s and 1930s urging the removal of cyclists from Britain’s roads — for “their own safety” — mainly were answered with polite acknowledgment rather than agreement.

Still, by the end of the 1930s, the Ministry of Transport was minded to channel cyclists and motorists on “their own tracks” and also urged restriction on pedestrian movement. Many miles of barriers (chains at first) were erected in London and elsewhere, corralling those on foot, forcing pedestrians to use the provided crossings.

In 1939, a House of Lords select committee formed to look at road deaths created what was, in effect, a motorist’s charter. The Alness committee argued that there should be fewer prosecutions for drivers and fewer speed limits and concluded that road safety could be improved by separating pedestrians (and cyclists) from motorists. Pedestrians were criticised in the report for being “unwilling to sacrifice any of their rights to the common cause of safety.”

Similarly, the March 1939 Report of the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents, generally known as the Alness Report, sniffed that “there is much thoughtless conduct amongst cyclists which is responsible for many accidents.”

The peers made 231 recommendations, including that children ten and under should be banned from public cycling (“children under seven cause 23.9 percent of the accidents to pedestrians,” the report claimed) and that segregation on the roads should be carried out with utmost urgency.

Cyclists, said the report, should get high-quality wide cycle tracks and that, once built, cyclists should be forced to use them. Motorists, decided the pro-motoring Lords, should be treated with a light touch by the law and should be provided with motorways and many more trunk roads. “Courtesy cops,” they suggested, would ensure motorists acted like gentlemen rather than cads.

Then war intervened. The Alness Report – derided by one Labour MP as a “tale of deaths and manglings … and extraordinary conclusions” – was moth-balled.

After the war, a House of Commons select committee dusted it down, and many of the report’s recommendations were taken forward, especially the pro-motoring ones, but, for a while at least, there would be no new “motoring roads” and certainly no provision for cyclists. Post-war austerity killed off putative plans for a national network of cycle tracks just as it killed off the building of motorways for the time being.

The somewhat abortive efforts to police the movement of cyclists in Britain, including building cycle tracks “for the safety” of cyclists, should be seen in the context of control, control that was anathema to the largely middle-class denizens of Britain’s cycling organisations and clubs who had lived through a 20-year golden period from the 1870s to the 1890s when cyclists ruled the roads.

We may be amazed that British club cyclists refused to ride on cycle tracks (even when some of those interwar cycle tracks were very good), but we benefit from hindsight and look on, with wonder, at the dense network of cycleways in the Netherlands as though they sprang from nowhere all at once.

Would cycling in Britain have become more popular had period cyclists accepted the Dutch-style separation of transport modes? This is discussed in the section of this study on compulsion.

Critically, cyclists were not protected at junctions on the 1930s-era cycle tracks, but this was a known omission. Had the network been expanded as planned, it could have been corrected subsequently, just as Dutch cycle tracks were continually improved.

Officialdom stated and restated that the creation of a cycle track programme was not to remove cyclists from the roads but was done for the safety of cyclists. But if this desire for safety was sincere, why were British cycle tracks not built extremely wide? The considerable period increase in cycling could have warranted the building of wide cycle tracks. A common complaint from motorists was that cyclists rode three and four abreast, so why weren’t the period cycle tracks made 12 or more feet wide to accommodate this?

CTC secretary G.H. Stancer told a parliamentary committee in 1938: “If it were possible to provide facilities that are equal to those that we enjoy now, with the additional advantage that they would not be shared by motorists, I think that cyclists would have no objection … If the paths are by any miracle to be made of such width and quality as to be equal to our present road system, it would not be necessary to pass any laws to compel cyclists to use them; the cyclists would use them.”

NOTES

Image credit for swipeable then-and-now pic above: Historic England archive, Historic England.

Imperial measurements are used throughout this study because the period cycle tracks were measured in feet and miles. It would be unwieldy to include, in brackets, the conversions to metres and kilometres.

[3] Western Avenue was one of the major new arterial roads that radiated out from London. London was where there were the greatest number of motorists in the UK, but also where political power resided. London’s new arterial roads were often used by members of the upper classes to speed them twenty miles or so from Mayfair to novel and decadent “roadhouses” with their swimming pools, clubrooms, and all-night drinking, where “high-rolling, metropolitan members of London society” would “race down” for a night of debauchery. The Ace of Spades roadhouse at Heston on the Great West Road, close to Western Avenue, did a “roaring trade” with these high-rollers, and had been built at a time when many parts of Britain were enduring desperate poverty. “One of London’s richest men, Lord Londonderry, who kept four chauffeurs for his Park Lane home, was happy to drive himself along arterial roads at great speed,” recounts the motoring historian Michael John Law.

The high-speed socialites were often the same politicians who demanded that cyclists should be removed from roads “for their own comfort and safety.” Motoring MPs and peers blamed cyclists for the fact that fast travel on the arterial roads was becoming more and more difficult. The numbers of cyclists on these roads increased in the 1930s – the average number of cyclists on Western Avenue at one point increased from 1,772 in 1931 to 6,515 in 1935 – but there were other, probably greater, reasons for the reduction in driving speeds, including the increasing number of cars on the roads. In London’s Home Counties there was a 400 percent increase in car ownership between 1926 and 1938. As suburban car ownership increased, progress on the arterials was interrupted by motor vehicles entering from the side roads that housed new homes and factories. Cyclists, in effect, became scapegoats for the congestion that they didn’t cause, a blame game that’s still played today.

See:

“Driving to the ‘Super’ Roadhouse,” Michael John Law, Aspects of Motoring History, The Society of Automotive Historians in Britain, 2016, 12. See also: M. Pugh, “We Danced All Night: A Social History of Britain Between the Wars,” 2008.

“Outer London Clubs And Cabarets – ‘the Ace of Spades’” (1933), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=84w9HCsZKHo ; see also:

“The Ace of Spades service station and swimming pool alongside the Great West Road (A4), Heston,” (1934),

http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/epw045358 .

Michael John Law, “Driving to the ‘Super’ Roadhouse,” Aspects of Motoring History, The Society of Automotive Historians in Britain, 2016, 12. See also: M. Pugh, “We Danced All Night: A Social History of Britain Between the Wars,” 2008.

“Cycle Census – Great West Road”, September 18, 1937, Ministry of Transport. (See: CYCLE TRACKS: Proposed construction, 1926-1943, Ministry of Transport, MT 39/127, National Archives, London.

The Motor Industry of Great Britain 1939, Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, 1939.

Ribbon Development and Sporadic Building, Greater London Regional Planning Committee Report, 1929. Many of the factories which sprang up along the Western Avenue from the early 1930s were bright, white and futuristic, some of them art deco in style. Today they are celebrated. However, in his 1951 Buildings of England volume on outer London, the famous architectural critic Nikolaus Pevsner said the Hoover factory – erected in 1932 – was “Perhaps the most offensive of the modernistic atrocities along this road of typical bypass factories …”

[4] Today this role is known as Transport Secretary.

[5] Stanley also wanted to see “authorised crossing places for pedestrians … instituted on large scale in London streets,” reported a newspaper. There would also be “propaganda aimed at reducing the mortality and accidents on the roads.” Daily Herald, 8th February 1934.

[6] Stanley also answered a parliamentary question about cycle tracks on 14th February 1934

“Only one such proposal has been submitted by a Highway Authority, namely, one in connection with the extension of Princess Road, Manchester,” he said.

[7] Daily Mirror, 16 March 1934.

[8] Brochure of Official Opening of Western Avenue by Leslie Hore-Belisha, December 14, 1934. See: London Metropolitan Archives, MCC/CL/L/CON/02/05842

[9] http://www.britishpathe.com/video/new-cycle-track-opened

[10] The Times, 15 December, 1934.

[11] The Scotsman, 24 August 1934.

[12] Memorandum No 483, Ministry of Transport, February 1937.

[13] Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, Peter D. Norton, MIT Press, 2008.

[14] The concept of the Ministry of Transport was originally introduced to parliament as the Ministry of Ways and Communciations. Ministry Of Ways And Communications

26 February 1919 https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1919-02-26/debates/9d1780b4-b24a-47cf-891e-9a955adce2f7/MinistryOfWaysAndCommunications

[15] Colonel R. W. Butler, a MoT divisional road engineer, told a Round Table meeting in Norfolk in 1935 that there had been a “remarkable increase in pedal cycle traffic … revealed by the 1935 census for the country as a whole. In 1931 the average number of pedal cyclists passing each census point in the county was 235, and in 1935 it was 357, an increase of 52 percent in four years.”

He continued: “The provision of cycle tracks can, however, frequently be justified not only on the grounds of public safety, but also on the grounds of economy. You will know, as I know, sections of road where at certain hours of the day congestion occurs because of the number of pedals cyclists on the carriageway. If the pedal cyclists were removed from the carriageway and accommodated on their own properly designed tracks the carriageway would continue to be adequate for the vehicular traffic using it, but if the pedal cyclists are not to be sparely accommodated there will be no alternative to the widening of the common carriageway. Cycle tracks should be normally 6ft. wide located on either side of the carriageway, and separated from the carriageway and footway by verges. Where the volume of cycle traffic is greater than can be safely accommodated on a 6ft. track additional tracks width should be provided in units of 3ft.”

Yarmouth Independent, 14 December 1935.

[16] Report by the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Prevention of Road Accidents (session 1938-39). https://archive.org/details/b32170312

[17] The Cock o’ The North restaurant/service station became a pub, but was demolished in 2005. A housing development has since sprung up on the site.

[21] In 1961 a committee appointed under Sir Walter Worboys reviewed traffic signs and font use. The result was the 1964 Traffic Signs Regulations, which specified a new standard national style based on a mixed case font.