SAVING LIVES OR RIDDING ROADS OF CYCLISTS?

Keeping cyclists safe: that was the main contemporary claim for the creation of Britain’s cycle track programme. This claim was stated thousands of times — in Parliament, in the press, in MoT correspondence and elsewhere. But does the claim hold water?

Transport minister Oliver Stanley, instigator of the programme in 1934, although it was officially introduced by his successor, appeared to be sincere when he cited safety as his main motivation. (As a non-motorist, it could be argued he had no skin the game.) In 1933, Stanley introduced the driving test and the 30 mph speed limit in the Road Traffic Act, arguing that “if the experiment fails, all it means is that a certain number of people have suffered some limited inconvenience for a certain amount of time. On the other hand, if we succeed, it means that we are saving human life.”

Such arguments cut little ice at the time with arch motorists such as Colonel J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon, a Tory MP and vice-chair of the Automobile Club. In 1940, he was made Winston Churchill’s Minister for War Transport and, in that role, signed off on several protected cycle tracks, but, back in 1933, he complained that Stanley was unfit to be transport minister.

“Curiously enough, [Stanley] is an ex-railway director, and not a motorist,” chided Moore-Brabazon.

“In these days, when everybody is a motorist, it is a very curious combination that a Minister should be those two things. I believe that a great many of his faults are due to his lack of experience of the maddening things that happen to you when you are actually driving a motor.”

Maddening things such as slowing down when near non-motorised road users, for instance. In the same speech, Moore-Brabazon said:

“It is no use getting alarmed over [deaths on the roads]. Over 6,000 people commit suicide every year, but nobody makes a fuss about that. It is true that 7,000 people are killed in motor accidents, but it is not always going on like that. People are getting used to the new conditions.”

He continued:

No doubt many of the older Members of the House will recollect the numbers of chickens that we killed in the early days. We used to come back with the radiator stuffed with feathers. It was the same with dogs. Dogs get out of the way of motor cars nowadays, and you never kill one. There is education even in the lower animals. These things will right themselves. It may well be that we have got to the peak of road accidents, and that, even within a year or two, people will realise the extreme change that has come over our life, and that very much greater care must be taken.

(The care had to be taken by those not in motor cars — a victim-blaming approach still with us.)

Despite objections, Stanley’s driving test and 30 mph speed limit plans passed. In a similar spirit of road safety, the transport minister later the same year said he was “prepared to consider any proposal submitted to me by the appropriate highway authority for the provision of separate tracks for pedal cyclists.”

But his successor, Leslie Hore-Belisha, and many others in power or positions of influence had an often stated ulterior motive. They wished to clear the roads of millions of proletarian cyclists to increase speeds — and hence assumed amenity — for the far fewer middle-class and elite motorists. According to official MoT statistics, transportation cycling boomed between 1931 and 1935.

“It should be borne in mind that 90 percent of the cycling population belongs to working-class families,” estimated the Camberwell Trades and Labour Council, part of the Trades Union Congress, in April 1937.

Sir Edmund Crane, chairman of Hercules Cycle and Motor Company, said that the “great body of cyclists are not particularly articulate. They have no considerable funds on which to draw for propaganda purposes; they do not possess the columns of the Press in same manner as the later comers to the road.”

He added:

The cyclist has been held in derision by thousands of unthinking people who, because they happen to be endowed with a larger share of this world’s goods, look upon the bicycle as something quite beneath their dignity, which would also be beneath their notice except that it continually thrusts itself upon them on every road they travel. These people would cheer on any alteration of the law that made the cyclist’s position on the road more difficult.

SAFETY

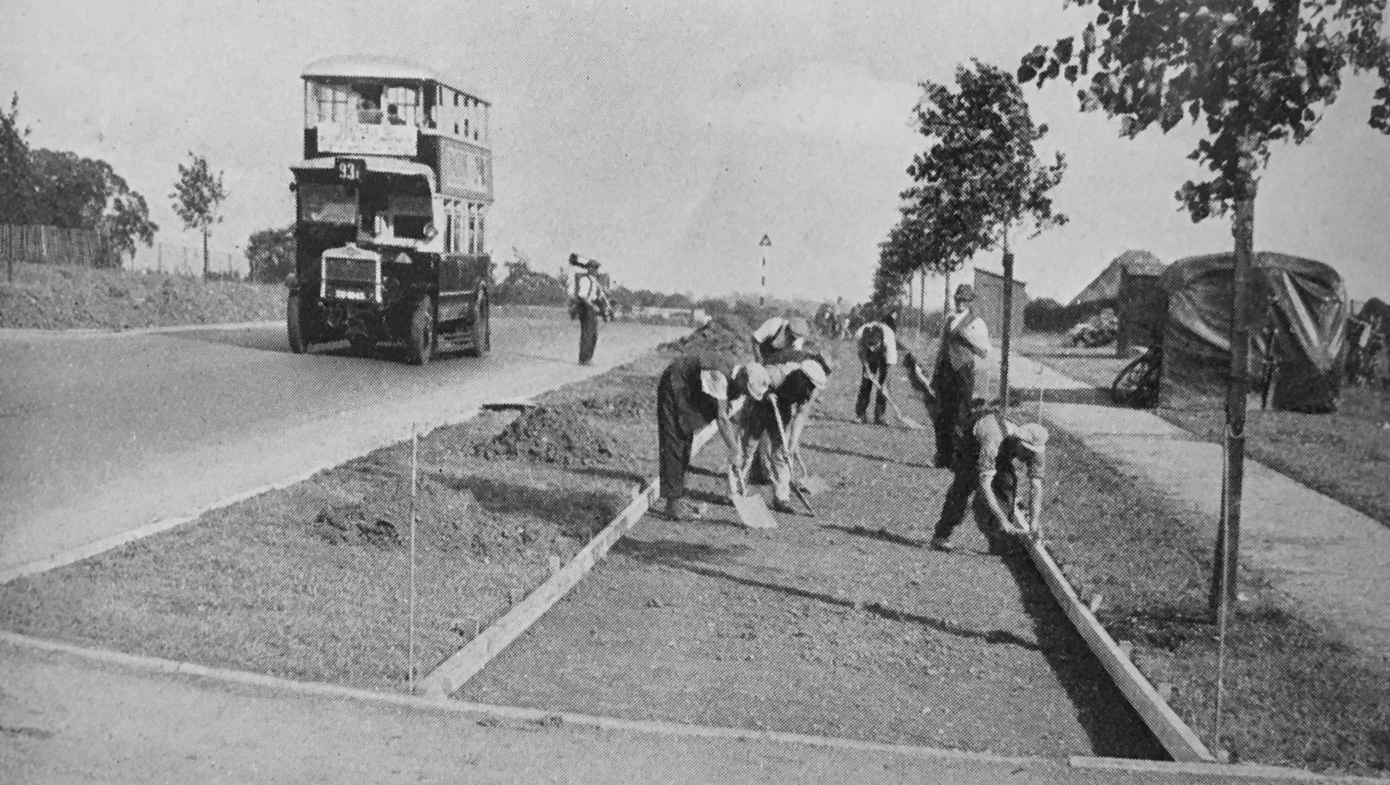

The brochure accompanying the ministerial opening of Britain’s first cycle track on 14th December 1934 led with the safety angle: “For workers traveling between their homes and the factory, for children proceeding to and from school, for holiday-makers intent on a country jaunt, these tracks should prove a boon and a safeguard.”

Doubling down on this angle, transport minister Hore-Belisha asked on the opening day: “Are not casualty lists and the number of accidents involving cyclists, themselves arguments for the provision of experimental tracks of this kind?”

“Of the 7,202 persons who died as the result of road accidents last year 1,324 were pedal cyclists,” he continued. “Out of the 184,781 non-fatal accidents, pedal cyclists were involved in 43,789. A distressing feature of these figures is that they disclose that about half of those who were killed were under the age of 21. The evidence before me shows that accidents to cyclists are increasing.”

Writing directly to cyclists in 1935, Hore-Belisha said he “realized the anxieties which must confront cyclists on the crowded roads of the country, and in order that they may get full enjoyment their excursions and be freer from risks and consequent apprehensions, have invited highway authorities to make a start with the provision of special tracks for them.”

To other audiences, Hore-Belisha was more honest about why the MoT pushed ahead with its cycle track programme.

As recounted elsewhere in this study, at a 1936 meeting of the Commercial Motor-users’ Association, an organisation not known for its interest in cyclist safety, Hore-Belisha pledged the “provision of nearly 500 miles of cycle tracks,” a statement which was “greeted with applause,” reported a newspaper.

“We at the Ministry will try to provide for, and anticipate, the transport industry’s demands upon the roads,” he told those gathered at the luncheon.

“I can promise you that we will proceed with vigour and determination to give you what you require,” stressed Hore-Belisha. Naturally, he made no similar pledges to cyclists, the numbers of which had massively increased by the mid-1930s.

In Parliament, Hore-Belisha admitted that providing cycle tracks wasn’t just to save cyclists’ lives but also to reduce congestion.

In a 1936 debate, an MP asked Hore-Belisha about the width of the Great Western Road in London. The transport minister replied “I am glad to say that they intend to put down cycle tracks there so as to relieve the congestion.”

In this he echoes beliefs held by many MoT officials. Writing an internal memo in 1934, the MoT’s northern division’s chief engineer, A.J. Lyddon, stated that the A565 Liverpool to Southport road was “notoriously thronged with cyclists” and that a proposed bypass of Formby would make the road more amenable to motorists.

“At a recent interview with Mr. Jackson, the Borough Engineer of Southport, I was informed that many motorists, himself amongst the number, had given up using this particular route on account of the danger due to the presence of so many cyclists on the road,” complained Lyddon, claiming that such large numbers of non-motorists was “affecting the influx of visitors to Southport.”

The MoT’s chief engineer, Colonel Bressey, wrote to Preston’s county surveyor suggesting “constructing a cycle track” on this bypass because the “proportion of cyclists is said to be exceptionally high.”

There was no mention of keeping this large group of people safe; the motivation was clearly the corralling of cyclists to enable faster progress by motorists, who hated the fact that those not in motors also used Britain’s new arterial roads, which they believed were for motorists alone, roads symbolic of modernity and speed.

But many club cyclists also loved the new arterial roads introduced in the 1920s and 1930s, for they were smooth, swooping, and perfect for their speed.

“It is good to be on the road… especially these great arterial roads and by-passes with plenty of traffic — keeps one alive,” wrote solo daily cyclist and author John Sowerby in 1938.

“The more poetically minded will rave about quiet lanes and byways,” he continued, “but give me the main roads and great highways to really enjoy cycling.”

He loved the newly built environment: “I gained the North Circular… What a road! Full of interest, circles or roundabouts, signals, the home of well-known wares and commodities. Square bridges, arched bridges. Many great arteries intersecting here and there.”

Such roads were busy with motor traffic on holiday weekends but less busy at other times. In effect, Britain’s cyclists — the majority users of the roads at that time — had been provided with speedways, and many baulked at the prospect of giving them up to ride on narrow, bumpy cycle tracks where they would have to ride single-file. They wanted to ride three, four, or five abreast, talking with their mates as they rode tempo out to tea rooms.

MoT traffic surveys showed how cycle use on these new arterials expanded fast in the mid-1930s. Road planners, MoT mandarins, and newspaper letter writers complained bitterly about being blocked by packs of cyclists.

“I was amazed when I saw the large number of club cyclists on the main roads last weekend,” wrote a cycle-trade visitor from South Africa.” His solution? Cycle tracks.

“There is a lot of talk today of tracks,” wrote club cyclist and journalist John R. Hetherington in 1936. “Motorists in fact are most anxious that cyclists should have special tracks to themselves,” he added, stating in italics this was “for their own safety!”

“The idea,” he snarked, “is that the motorist owns the road, and merely suffers offers to use it.”

Cycling organizations believed the actual motive of the cycle track-building programme was to force cyclists to use narrow, inferior paths in order to increase the utility of motoring. A pamphlet produced by the Cyclists’ Touring Club voiced this concern:

It is impossible to escape the conclusion that most people and organisations who advocate cycle paths are not actuated by motives of benevolence or sympathy… If they did, as they suggest, recommend them merely because so many cyclists were being killed they would naturally recommend separate paths for motor cyclists as well, for the death rate among motor cyclists is the highest of all road users and fifteen times as great as that among cyclists. A great deal of the cycle-path propaganda is based on a desire to remove cyclists from the roads. That is why the request for cycle paths is so often accompanied by a suggestion that their use should be enforced by law. Therein lies a serious threat to cycling.

The CTC also believed in the out-of-sight, out-of-mind theory that once cyclists were removed from some roads, motorists would not want to see them on any roads:

Providing some roads with cycle paths would naturally confirm inconsiderate motorists in a false belief that they need to have less regard for other classes of road users. Driving would become faster and more reckless on all roads, including the majority of roads that could not be provided with cycle paths.

WAR EFFORT

By the end of the 1930s, the motivation for building cycle tracks had changed. Cycling — a reliable form of cheap, practical transport for the masses — was adopted and encouraged as part of the war effort.

Petrol — and therefore driving — became rationed, with a total ban on the sale of fuel for private motoring being introduced in July 1942, although many private cars had been put away in storage before that.

Blackout restrictions, the suspension of driving tests, and speeding military traffic meant it remained deadly on Britain’s roads. In the first few months of the war, it was more dangerous to be on the roads than in the armed forces. Later, in the twelve months between September 1941 and August 1942, 7,693 road users were killed, of which 1,155, or 15 percent, were cyclists.

Nevertheless, cycle use soared, and it became a national imperative to protect cyclists. This new duty of care is shown in a wartime instructional film by the Ministry of Information. Splinters 1943 encouraged Britons to keep the wartime roads clear of tyre-ripping glass shards by kicking these “razor-edged splinters” to the kerb. “Here come the workers, in hurrying ranks/ to build us our battleships, bombers and tanks,” boomed the received pronunciation narrator over footage of commuter cyclists.

A broken milk bottle rips open the sidewall of a worker’s bicycle. “His tyre is gashed and can’t be repaired / whilst rubber is short and can hardly be spared,” chides the MoI film.

“If you see broken glass where bicyclists ride/don’t leave it but kick it away to the side/don’t hinder the war effort/keep the road clear for workers …”

Many of the later cycle tracks were built with the war effort in mind, speeding cyclists to munitions factories, military bases, and more.

Plenty of post-war movies portrayed a wartime bucolic England of winding country lanes. However, in the real world, many RAF stations and the like were reached by modern-looking dual carriageways, often fitted with cycle tracks.

The Royal Navy Propellant Factory at Caerwent was sited close to the A448 Caerwent bypass, which opened in 1932. Its retrofitted cycle track — installed in 1939 at the same time as the factory — was camouflaged.

According to Admiralty plans marked “Secret,” a double-sided cycle track on the road next to the base was to be painted to look like the surrounding fields. The cycle track had been planned in 1936, according to a report in the Gloucester Citizen. It was opened in early 1939, paid for with a 100 percent grant from the Ministry of Transport, according to the Western Mail.

The plans for the factory had been first drawn up in the summer of 1936, with one of the essential requirements being that, because of the manufacture of nitroglycerine, it should be located away from areas of high population but sufficiently close to provide an adequate workforce — within cycling distance, in fact.

The Royal Ordnance Force factory of ROF Chorley in Lancashire was reached by cycle tracks installed on Euxton Lane in anticipation of the influx of thousands of workers. The new factory employed over 1,000 production workers by the outbreak of WWII, rising to 40,000 at the height of the war.

Euxton Lane was widened — with footways and cycle tracks included — in January 1937 at roughly the same time as the building of the munitions factory. (According to local historian Steve Williams, ROF Chorley was used to fill the “bouncing bombs” used in the famous Dambusters raid of May 1943.)

During WWII, almost all of the 400 or so factories on Trafford Park in Manchester — today’s Trafford Centre — were devoted to the war effort. By 1945, 75,000 workers were commuting to the estate daily, many on bicycles, including on the cycle tracks on Barton Dock Road, completed in 1942.

Rolls-Royce Merlin engines — used to power both the Spitfire fighter and the Lancaster bomber — were built under licence by Ford at Trafford Park. The 17,316 workers employed at the Ford factory, opened in 1941, had produced 34,000 engines by the end of the war.

Rolls-Royce also had a factory on Pyms Lane in Crewe, opened in 1938. At its peak in 1943, 10,000 people were employed at the factory. Many would have cycled to work and might have therefore used the superlative cycle track installed speedily on Pyms Lane at the same time as the factory building.

The Chester Road cycle tracks in Erdington, Birmingham, opened 1936/7, would have been used by workers cycling to the Castle Bromwich aircraft factory. This was the largest purpose-built aircraft factory of the war, producing the iconic Vickers Supermarine Spitfire and the Avro Lancaster bomber.

NOTES

[1] FOOTWAYS (CYCLISTS).

HC Deb 30 November 1933 https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1933/nov/30/footways-cyclists

Road Traffic Bill

10 April 1934

https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1934-04-10/debates/c2c5402a-42ee-46b5-90b8-29e3691c42ec/RoadTrafficBill?highlight=%22errand-boy%20comes%20round%20on%20his%20bicycle%22#contribution-dc8e9c30-5b16-4842-a7cb-739d5a7a3b97

[2] Daily Herald, 3 April 1937.

[3] London Metropolitan Archives, MCC/CL/L/CON/02/05842

[4] Manchester Guardian, December 15, 1934.

In 1936-7 there were 6,539 people killed on the roads, of which 1,440, or 22 percent, were cyclists. (526 cyclists died in incidents in which no mechanically propelled vehicle was involved.)

[5] Western Morning News, 18 April 1935.

[6] Birmingham Daily Gazette, 26 March 1936.

[7] HC Deb 01 April 1936 vol 310 cc1987-8 1987

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1936/apr/01/dual-carriageways#S5CV0310P0_19360401_HOC_148DUAL CARRIAGEWAYS.

[8] The suggestion as to the location of cycle tracks has previously been considered in connection with

the provision of footways, but has never been generally taken up. There appears to be no reason why the

suggestion should not be adopted for cycle tracks in non-built-up areas.

With regard to the method of construction suggested by Mr. Fay, it is doubtful whether rolled ashes

would be suitable and acceptable to cyclist, and if the use of the track is to be permissive a surface comparable with that of the carriageway, from a cyclist’s point of view, will be necessary to ensure any degree of usage.

The road mentioned by Mr. Fay (Liverpool Southport, A.565) is via Formby and is notoriously thronged with cyclists. At a recent interview with Mr. Jackson, the Borough Engineer of Southport, I was informed that many motorists, himself amongst the number, had given up using this particular route on account of the danger due to the presence of so many cyclists on the road, and he expressed the view that this was in some measure

affecting the influx of visitors to Southport from that direction.

He would welcome an improvement of the road. The County Council have under consideration a by-pass of Formby, but this scheme has not been given a high degree of priority by the County Surveyor. The road appears to lend itself to the provision of a cycle track on the lines suggested by Mr. Fay.

I return herewith the letter which accompanied your minute.

From A.J. Lyddon, Divisional Road Engineer, Northern, 6th July 1934. Ministry of Transport archives.

[9] John Sowerby was the nom de plume of Percival Bennett, author of the best-selling 1939 book “I Got On My Bicycle (Frederick Muller Ltd), a diary of his 40+ mile daily rides between 20th April to 17th October 1938, when he was 57.

[10] Bicycling News, 26 August 1937

[11] John R. Hetherington, Cycling for Fun, Birmingham, 1936

[12] Making the Roads Safe: The Cyclists’ Point of View, Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1937.

[13] Making the Roads Safe: The Cyclists’ Point of View, Cyclists’ Touring Club, 1937.

[14] In the first four months of the war, 4,133 people were killed in road crashes, 2,657 of them pedestrians.See: Wartime: Britain 1939-1945, Juliet Gardiner, 2004.

[15] From a speech by the transport minister to the Pedal Club on March 14th, 1944.

[16] “Splinters 1943” is similar to the famous “Night Train” film of 1936 which had the W.H. Auden poem valorizing the postal service.

[17] Pathe film script

Here is a milk bottle perched on a wall

here is a kitten and here is a fall

here is a razor-edged splinter of glass lying

in wait for whatever may pass

Here come the workers in hurrying ranks

to build us our battleships, bombers and

tanks

They’re off to the factory shipyard

and shop but Bill is unlucky he’s

brought to a stop

His tyre has been

gashed and can’t be repaired whilst

rubber is short and can hardly be spared

A long way to go and he’s bound to be

late the battleships, bombers and tanks

have to wait

They’re urgently needed

the

Bill isn’t here doesn’t his fault but

the lesson is clear take care of your

milk bottles don’t let them fall and

don’t put them out on the top of the

wall if you see broken glass where

bicyclists ride don’t leave it but kick

it away to the side don’t hinder the war

effort keep the road clear for workers

and services all in top gear you’re

saving our rubber in country and town

and you’re helping our fighting men

don’t let them down

Splinters 1943 (1943)

[18] Caerwent-Crick Arterial Road (A48): Camouflage of foot paths and cycle tracks. Scale 1:500

Ref DEFE 222/664, National Archives.

[19] Cyclists’ Track on Chepstow Road

A start has been made on the construction of the first double-track highway in Wales and Monmouthshire on the Newport-Chepstow road.

It will extend from the Caerwent by-pass to Crick and will form another link in the Great West Road. There will be a grass verge of16ft. between the up-and-down tracks, each of which will be 20ft. wide. The scheme also provides for 6ft. concrete cycle tracks and tarmac pavements, separated by grass verges. It will take about 16 months to complete.

Gloucester Citizen, 29 October 1936

[20] Reconstruction of a section about three-quarters of a mile in length of the Newport-Chepstow trunk road, route A48, between Caerwent and Crick, costing £20,146, the Ministry of Transport contributing 85 percent and 100 per cent grants.

Western Mail, 9 January 1939

[21] A History of Royal Ordnance Factory, Chorley, Mike Nevell, John Roberts & Jack Smith. Carnegie Publishing Ltd, 1999.

[22] https://www.baesystems.com/en-uk/heritage/castle-bromwich