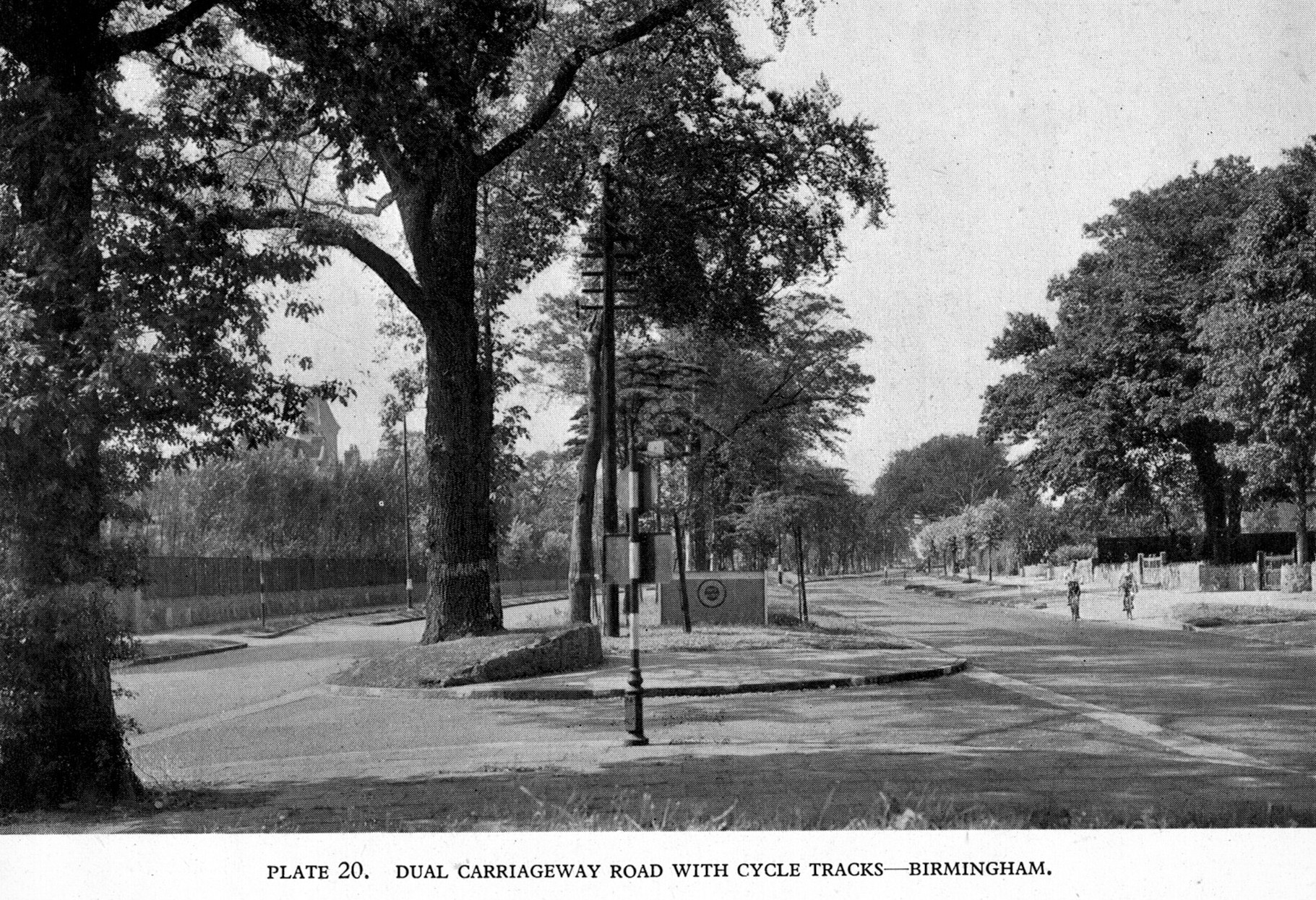

Cycle tracks both sides of Chester Road, Erdington. The building on the left gave the name to Orphanage Road, enabling this location to be identified.

“The provision of separate tracks for cyclists are features of modern development,” wrote Birmingham’s chief engineer Herbert Manzoni in 1937, adding “they have been in use for many years … in certain Continental countries … and it has been found that they are much used and well favoured.”

In a piece for Municipal Engineering he included a photograph of the Chester Road cycle track he had built in Erdington, Birmingham. This had a “width of 9ft, and, except for the intersection with the main carriageway, which is surfaced in concrete for ease of distinction, they are formed in tarred limestone, and are bounded on each side by a concrete kerb, the tracks being separated from the main carriageway by a reservation of a width of 4ft.”

Same location as photo above. The orphanage was demolished some years ago.

In the same journal some months later he talked again about the 1.2 mile cycle track scheme on Chester Road: “The width of the new road is 120ft, the twin carriageways being 24ft wide with a central grass reservation 22ft in width. The 25ft wide footpaths accommodate a 9ft wide cycle track … A 3ft grass strip, in which trees will be planted, is laid between the cycle track and the 6ft flag paved footway, whilst a 3ft strip of red ashes completes the width from the flag paving to the fences.”

He continued: “The cycle track is surfaced with 2.5in of tarred limestone laid on a bed of 3in of ashes.”

Photo of Chester Road from Manzoni’s 1937 article in Municipal Engineering.

Manzoni was Birmingham’s all-powerful chief engineer for an impressive 28 years and it was on his watch that the city became so dominated by the car.

The heart of Birmingham — including many much loved historic buildings — was ripped out by Manzoni. He turned Birmingham into Britain’s “motor city,” commissioning the ugly inner ring road and demolishing much of the city centre, even sweeping away buildings untouched by the bombs of the Birmingham Blitz in 1940. His Brutalist Bull Ring Centre, finished by the mid-1960s, was considered the height of fashion when first built, but enthusiasm for it quickly waned. Much unloved, it was replaced by the shiny Bullring Shopping Centre in 2003.

Manzoni, Birmingham’s City Engineer from 1935 until 1963, was a modernist. He built for motorists not because there were lots of cars in Birmingham but because he felt there ought to be lots of cars in Birmingham. He was no sentimentalist. “Most of our buildings put up in the last hundred years are finished,” he said in 1954.

“Throughout most of the country we shall see complete rebuilding of our cities and towns.” Cities should be inviting to those driving cars, he thought. “I see no reason why traffic in this country should not reach the proportions of traffic in America … that is – one vehicle per adult, four times as much as we have got now,” he wrote in 1955. “But it won’t matter so much if all our roads are right.”

And for roads to be right, they had to be “fast” roads, felt Manzoni. Fast for motorists, such as himself. And fast even into the centre of cities.

Wide cycle tracks and footways on Chester Road, Erdington.

For engineers and planners from the 1920s onwards a key way of increasing speeds for motorists was to build wider, straighter roads. And there was little point building such arterial roads if inferior cyclists got in the way of their betters.

Thanks to its burgeoning automotive industries Birmingham was more motor-myopic than other cities but even car factory workers rode bicycles. In 1937, 13.5 percent of the employees at the Austin Motor Works at Longbridge cycled to work. Unusually for the time, 14 percent drove to work.

The cycle tracks Manzoni constructed in Erdington were planned in 1935.

Car blocking the period cycle track on Chester Road, Erdington.

“The proposal to construct experimental tracks for cyclists on a portion of Chester-road, between Sutton-road and Pype Hayes-road, was the only subject of debate at yesterday’s meeting of Birmingham City Council,” reported the Birmingham Daily Gazette in December 1935.

“For an hour the Council discussed the merits of the experiment, and it was then decided by a large majority to provide separate tracks for cyclists on this section of Chester-road,” continued the newspaper.

As well as being a busy through road — it was the route from London to the Mersey Tunnel, said Manzoni — it was also well used by workers commuting to and from major factories in the Castle Vale area, including Fort Dunlop.

Built in 1916, this building was used to store tyres made on the site by Dunlop Rubber Co. Ltd which had operated in Erdington since 1901 manufacturing Dunlop tyres, initially for bicycles and later for motor vehicles.

Cars parked on the period cycle track on Chester Road.

At its peak in the 1950s, 10,000 people worked at Fort Dunlop and an entire village, known as Tyretown, developed around the site including shops, a cinema, concert hall and a sports club.

Many Fort Dunlop workers lived in municipal houses at Pype Hayes.

Between the wars, Birmingham built over 51,000 new council homes — more than any other local authority in the country outside London — in satellite suburbs, including Erdington.

Footway-riding cyclist could have been on the cycle track if it wasn’t blocked by motorists.

During World War II the Chester Road cycle tracks would have been used by workers cycling to the Castle Bromwich aircraft factory. This was the largest purpose-built aircraft factory of the war producing the iconic Vickers Supermarine Spitfire and the Avro Lancaster bomber.

The site was later developed into the Castle Vale housing estate. Some of the buildings from the WWII factory are still used by Jaguar Land Rover.