In his 1937 documentary short Roadways — produced for the General Post Office Film Unit — Brazilian film director Alberto Cavalcanti portrayed the newly-built arterial roads of the 1920s and 1930s as bright white examples of modernity. “Concrete bypasses replaced the old coach roads through the towns,” intoned the narrator, adding that the period’s new 30 mph speed limits, driving tests, roundabouts, and zebra crossings signified the start of an “era of control.” And, as Cavalcanti showed with images of cloth-capped working class cyclists riding on newly minted infrastructure, an intrinsic part of this control was the cycle track.

Great things had been expected of the first tracks — not least getting anachronistic cyclists out of the way of “modern” motor traffic — and it’s worthwhile setting the initiative in its historical context, looking at the legislative and social environment before, during, and after the programme’s creation in 1934.

Encouraged with generous MoT grants for the best part of ten years, Britain’s national cycle track programme was initially ambitious and ostensibly created to save cyclists’ lives. However, of the 100 or so cycle tracks installed, cyclists only used a few of them in great numbers. Largely deemed a failure by postwar officialdom, the programme was not restarted, as promised, when the road and motorway building frenzy began in 1958.

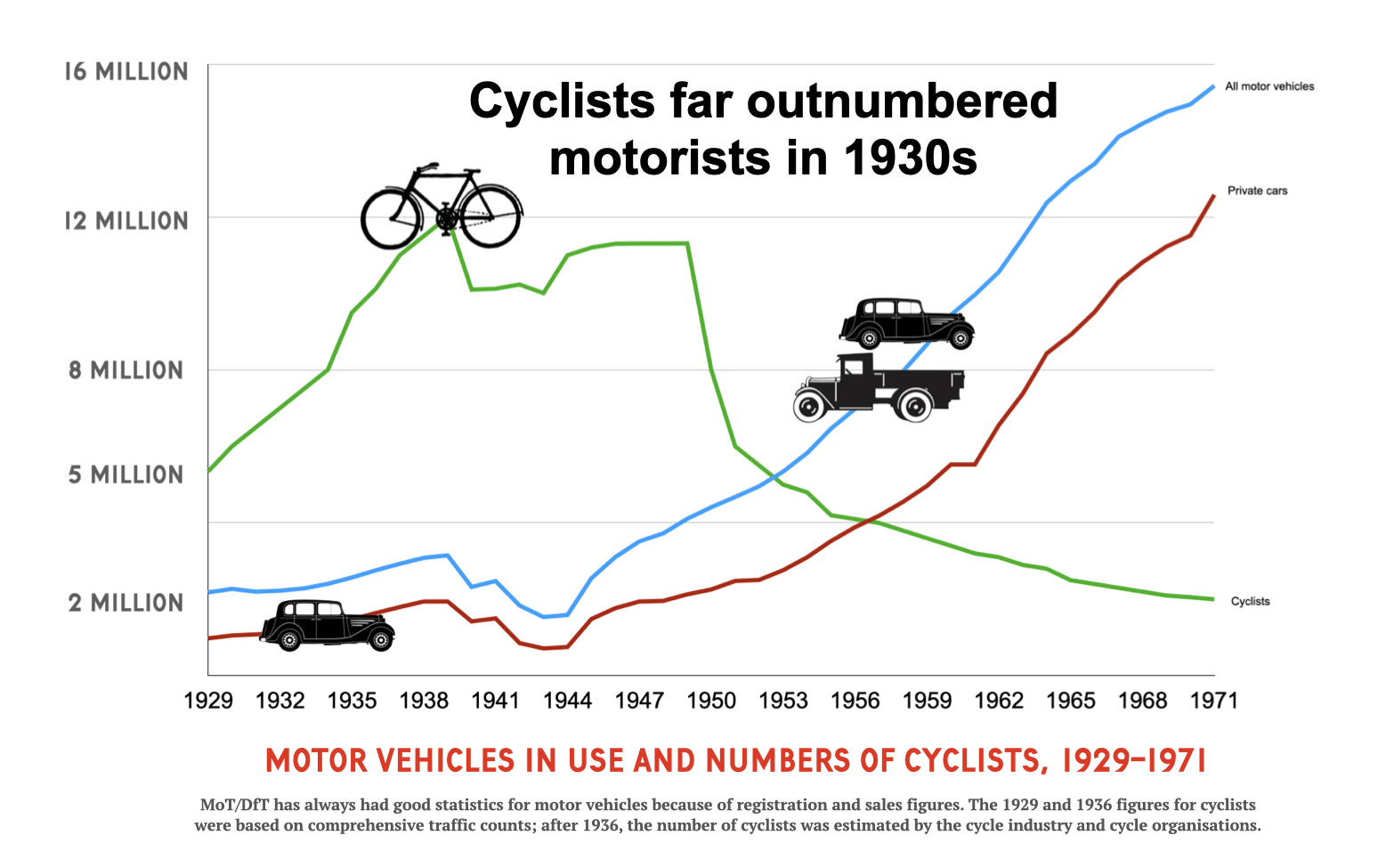

In the 1950s and 1960s, the government expected that cycling — in steep decline since 1949 — would wither to nothing. It was believed that mass motorisation — a seemingly unstoppable force that had to be mollycoddled for economic, political, and social reasons — would kill off cycle use.

A series of road safety reports from the 1940s through the 1960s demonstrated that if cycling were to disappear completely, it would have been of little concern to the government.

A 1942 report from the Ministry of War Transport recommended that British cyclists should be provided with cycle tracks. Still, the report’s author, Sir Herbert Alker Tripp, acknowledged the defects in existing tracks:

The use of cycle tracks, as in Holland and Denmark, is regarded by many people as the main hope. Unfortunately, cycle tracks break off at all junctions, which are just the spots where accidents are most frequent and protection is most needed. Nor are the cycle tracks themselves as good as they sound. At the entry of every minor road the cyclist finds he has to bump over the gutter and camber of the minor road; motor vehicles trying to emerge from these roads pull right athwart his track … mothers and nursemaids with perambulators use the ramps at the road junctions and thus obstruct the cyclists.

Tripp was a police officer, town planner, and poster artist (all simultaneously — twenty of his bucolic watercolours were reproduced as posters for railway companies). As assistant commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in the 1930s, he oversaw London’s traffic. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Tripp was a “passionate motorist and cyclist” and was especially interested in reducing the death toll on Britain’s roads. He felt this would be best achieved by training cyclists and pedestrians in the new road order: motorists now came first. When non-motorised road users bristled at his suggestions, he came to believe that physical measures would have to be employed instead — pedestrians should be penned in at road crossings, and cyclists should be corralled on tracks.

Gentlemen of education and position in their fast motorcars would be less likely to be caddish if they were given free rein on roads, he felt. And for that to happen, the only solution would be to separate transport modes. Perhaps instructively, Tripp preferred the word segregation.

Tripp developed his ideas in his 1942 study, Town Planning and Road Traffic, recommending car-free, pedestrian-only shopping precincts, bridges, and underpasses in town centres to keep pedestrians and cyclists apart from motorists. Critics complained that this would mean drivers would get ground-level access to the streets, but all other users would have to climb into the sky or descend underground. Such plans were broadly welcomed by the establishment of the day, and architect and town planner Colin Buchanan later adopted the ideas in his team’s internationally influential 1963 report, Traffic in Towns.

Tripp was not one of the town planners appointed to a 1943 Ministry of War Transport committee looking to reconstruct postwar Britain, but his segregationist influence can be seen throughout the committee’s report, published in 1946. Design & Layout of Roads in Built-up Areas recommended separation for cyclists, fretting that “conditions obtaining in early postwar years will tend still further to popularize the cycling habit.”

Wartime casualty figures led the report’s authors to the “inevitable conclusion that by far the best preventative of accidents to pedal cyclists lies in their segregation from motor traffic, for it is clearly unsound that a running surface should be used at one and the same time by heavy motor-driven vehicles capable of developing high speed and by light and unstable vehicles such as pedal cycles.”

The report discussed the merits of “motor ways,” “pedestrian ways,” and “cycle ways.” These cycleways were “for the exclusive use of pedal cyclists, separate from the general road system …”

“Segregation … should be the key-note of modern road design,” stressed Design & Layout. “Police supervision would be necessary to ensure that … cycle ways are not used by other classes of traffic or otherwise abused” and such “segregated tracks for cyclists” should be provided “as a matter of course on arterial, through- and local-through routes…”

The authors took a dig at the Cyclists’ Touring Club — one of the organisations consulted for the report — snarking, “We regard it as unfortunate that attempts should be made in any quarter to discourage cyclists from using [cycle tracks].”

The cessation of the proposed cycle-track building bonanza in the late 1940s had almost nothing to do with opposition from cycling organisations, and everything to do with the desire to provide mainly for the motoring classes, which, at this time, were mostly the likes of leading police officials, architects, town planners and, of course, politicians.

Traffic in Towns, the 1963 report mentioned earlier, featured cycling only in passing; lead author Colin Buchanan believed that urban cycling would soon die out:

“There is a universal demand made upon me … for cycling tracks. I find the pressure irresistible.”

Transport Minister Leslie Hore-Belisha,1938

… it is a moot point how many cyclists there will be in 2010… [This] does affect the kind of roads to be provided. On this point we have no doubt at all that cyclists should not be admitted to primary networks, for obvious reasons of safety and the free flow of vehicular traffic… It would be very expensive, and probably impracticable, to build a completely separate system of tracks for cyclists.

This was an admission that the 1930s cycle track programme had failed. Yet it had started with high expectations.

“There is a universal demand made upon me … for cycling tracks,” Hore-Belisha told the British Electrical Development Association in 1938. “I find the pressure irresistible,” he stressed.

This pressure was exerted from many angles — most of them motor-centric — but it was also due to the government’s new, post-WW1 desire to impose control with more state intervention, including road rules.

One of the most significant features of British government in the 1920s and early 1930s was the extension of the role of the state into the social and economic life of the country. Whilst upholding the traditional virtues of a free market economy and opposing what was seen as quasi-socialist measures, successive governments introduced more and more legislation that increased the role of the state.

The previous laissez-faire attitude of allowing motorists to do what they liked, where they liked, and at any speed they liked had proven costly in lives lost, rights trampled, and landscapes despoiled.

In the 1920s and early 1930s, motoring organisations had been bitterly opposed to any restrictions imposed on drivers, but once the first few road safety measures were enacted, they demanded that pedestrians and cyclists, who posed little danger to themselves or others, also became subject to similar state control.

As explained elsewhere in this project, the original architect of the new rules for motorists — and soon thereafter, the cycle track program — was Minister for Transport Stanley Oliver, a non-motorist. Like other transport ministers before and since, he wished to regulate motoring by seeking motorists’ consent; motoring had a thick veneer of assumed respectability even before it was taxed and, therefore, became the “cash cow” of so many period and modern complaints.

This consent was not forthcoming, and Stanley’s introduction of the Road Traffic Bill — which proposed the driving test and 30 mph speed limit — was opposed by motorists and their representative organisations. Nevertheless, the act became law in 1934, although it fell to Stanley’s successor to introduce it in parliament.

Three years later, the government took control of “principal roads” following the 1936 Trunk Roads Act. This transferred direct control of more than 180,000 miles of highway from county councils outside of London to the Ministry of Transport, creating the sort of national system of routes for through traffic first advocated by cycling groups in the 1880s.

SLAUGHTER

The 1930s, for poet W. H. Auden, was a “low dishonest decade,” an era blighted with high unemployment, extremist politics, and, by the end of it, the menace of impending, unstoppable war. It was also, notably, a decade of road deaths. In a speech he gave in the House of Commons on 28th April 1936, Labour MP Aneurin Bevan accused the then Chancellor of the Exchequer of being an “assassin of hundreds of little children” because he would not spend money on making Britain’s roads safer.

“Last year there were 228,000 people killed or injured on the highways of this country,” complained Bevan, “and I believe every hon. Member will agree that that appalling casualty list could have been appreciably reduced had there been better roads. I think there can be no doubt that had there been cycling tracks, proper pathways for children, improved corners, non-skid surfaces, and so on, there would have been a very substantial reduction in the number of casualties.

“[The] roads of the country need to have a great deal of money spent on them in order to make them safer. Therefore, is it not admitted that had the money been spent the roads would have been safer, and that if they had been safer the children would have been alive? How can you refute the submission that the Chancellor is a cynical assassin?”

Bevan’s view — common before 1920 — was becoming a minority one, with most people becoming accustomed to the dangers associated with motoring, private and public.

“The average distance between home and work was increasing before the war and has taken an upward leap in recent years,” said the Road Plan for Lancashire 1949, going on to demonstrate an acceptance that wider, faster roads — whether for private cars or public buses — was now commonplace.

“The majority of persons, particularly among industrial and business workers, probably prefer to live at some distance from their work … It is difficult to place too high a value on the economic and social benefits which the provision of an adequate road system would confer on … the road-using public,” continued the plan.

“An economic factor would also arise from the consequent reduction in costs of travelling both by motor-coach and by car. Reduced maintenance and running expenses would in the long term raise the number of people able to afford private cars.”

The plan — which presumed mass motorisation — was written at the same time as the government’s Special Roads Bill.

Minister for Transport Alfred Barnes (a one-legged former silversmith) introduced the Bill in 1948. This would eventually lead to the creation of Britain’s motorway network. But the bill also promised “special roads for cyclists.” The bill became the Special Roads Act in 1949.

Special roads for cars — motorways — could now be constructed. The first wasn’t started until 1958, but they came thick and fast in the 1960s. Back in 1948, newspapers reported that the Special Roads Bill would also see the building of cycle tracks. And just as cyclists would be fined for riding on motorways, the transport minister promised that pedestrians would be fined for straying on cycle tracks. Introducing his bill, Barnes stressed that “everybody” benefited from motorisation:

It will be a mistake for anyone to assume that the Bill is promoted to satisfy the selfish interests of the private motorist. It is nothing of the kind. It is often overlooked that nowadays we are all motorists, whether or not we drive a private car. Everybody travels on buses or coaches and the greater proportion of our domestic and personal needs are delivered by motor van.

Critically, the Labour politician believed national highway authorities should pay for major motoring roads, but “special roads for pedestrians and cyclists” should be paid for by local highway authorities. And these “special roads” were deemed to be recreational rather than for practical, everyday travel:

I should emphasise … under the powers given to them to construct a special road, highway authorities could determine that the only classes of traffic using that road should be motor vehicles. These same powers can … be used by county highway authorities for the construction of special roads for pedestrians and for cyclists — across, for instance, a national park, along a river bank, across mountain, moor, or the coast line. [This] responsibility will rest upon local highway authorities, who ought to meet the cost of special roads of this type.

| YEAR | TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLES | CARS | CYCLISTS (estimates in italic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1929 | 2,181,832 | 980,886 | 5,343,000 |

| 1930 | 2,273,661 | 1,056,214 | |

| 1931 | 2,200,708 | 1,083,457 | |

| 1932 | 2,227,099 | 1,127,681 | |

| 1933 | 2,285,326 | 1,203,245 | |

| 1934 | 2,405,392 | 1,308,425 | 8,000,000 |

| 1935 | 2,570,155 | 1,477,378 | |

| 1936 | 2,758,346 | 1,642,850 | 10,123,000 |

| 1937 | 2,928,828 | 1,798,105 | 11,000,000 |

| 1938 | 3,084,896 | 1,944,394 | 11,500,000 |

| 1939 | 3,148,600 | 2,034,400 | 12,000,000 |

| 1940 | 2,325,000 | 1,423,200 | |

| 1941 | 2,477,800 | 1,502,600 | |

| 1942 | 1,840,400 | 857,700 | |

| 1943 | 1,537,300 | 717,500 | |

| 1944 | 1,592,600 | 755,400 | |

| 1945 | 2,552,500 | 1,486,600 | |

| 1946 | 3,106,810 | 1,769,952 | |

| 1947 | 3,515,444 | 1,943,602 | |

| 1948 | 3,728,432 | 1,960,510 | |

| 1949 | 4,107,652 | 2,130,793 | 12,000,000? |

| 1950 | 4,409,223 | 2,257,873 | |

| 1951 | 4,677,888 | 2,480,343 | |

| 1952 | 4,957,396 | 2,508,102 | |

| 1953 | 5,340,222 | 2,761,654 | |

| 1954 | 5,825,447 | 3,099,547 | |

| 1955 | 6,465,433 | 3,525,858 | |

| 1956 | 6,975,962 | 3,887,906 | |

| 1957 | 7,483,489 | 4,186,631 | |

| 1958 | 7,959,313 | 4,548,530 | |

| 1959 | 8,661,980 | 4,965,774 | |

| 1960 | 9,439,140 | 5,525,828 | |

| 1961 | 9,965,300 | 5,978,500 | |

| 1962 | 10,562,800 | 6,555,800 | |

| 1963 | 11,446,200 | 7,375,000 | |

| 1964 | 12,369,200 | 8,247,000 | |

| 1965 | 12,939,800 | 8,916,600 | |

| 1966 | 13,285,716 | 9,513,368 | |

| 1967 | 14.096,000 | 10,302,900 | |

| 1968 | 14,446,500 | 10,816,100 | |

| 1969 | 14,751,900 | 11,227,900 | |

| 1970 | 14,950,200 | 11,515,100 | |

| 1971 | 15,434,400 | 12,580,600 | 2,000,000? |

Because bicycle infrastructure was now classified as “local,” it had a lesser status and was more likely to be provided on a whim; in other words, rarely.

Cyclists soon became controlled not by government-installed infrastructure but by motor traffic. In the 1950s and 1960s, cycle use fell precipitously as roads filled with increasing numbers of motor vehicles. In 1949, just over 4 million motor vehicles were in use, half of which were private motor cars. By 1971, this had more than tripled to 15.4 million motor vehicles, of which 12.5 million were private cars.

As shown by the figures above, the government had accurate information on the number of cars in use as well as the number of everyday cyclists. After the comprehensive MoT traffic census of 1936, no further data was collected for the number of cyclists. Instead, the precipitous decline in cycle use was measured — less accurately — through the national travel survey. As the adage goes: you measure what you treasure.

NOTES

[1] An “arterial road” is a period term for a major route, often as a radial route or bypass. The term was used extensively in the 1920s and 1930s, including on mapping, to the extent that roads actually used the term in their name, such as the A20 Sidcup Arterial Road in Kent, opened 1923.

[2] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/1356049/index.html

[3] Social housing – council houses. utopian future, meant for the aspirational working classes.

https://municipaldreams.wordpress.com/?s=WYTHENSHAWE&search=Go

Working-class suburbanites got the worst deal from both public and private transport. New suburban council estates were often, in their early days, remote from tramlines and railway stations, leaving a long walk before a commute to work. Despite the prominence of the garden city model at this time, little provision was made for work within easy access of home. The technology that provided independence and faster travel for workers was the humble bicycle. The reduction in new prices and a wide secondhand market meant that cycling was a possibility for those in regular work. Bicycles were used for commuting to work over long distances and for more local use. For some better-off working men,

[4] Herbert Alker Tripp, Town Planning and Road Traffic, E. Arnold & Co., 1942.

[5] Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, May 2013, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/98024 .

[6] Design & Layout of Roads in Built-up Areas, Ministry of War Transport, HMSO, 1946.

[7] Road travel was awfully dangerous during the war, especially at night with cars traveling with dimmed lights because of black-out rules. An astonishing 9,169 people lost their lives on the roads of Britain in 1941, almost 3,000 more than during prewar years.

[8] “More Cycle Tracks? Minister Says Demand Is Irresistible,” The Citizen, March 16, 1938.

[9] https://poets.org/poem/september-1-1939

[10] http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1949/32/enacted .

[11] http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1948/nov/11/special-roads-bill#S5CV0457P0_19481111_HOC_320 .

Because bicycle infrastructure was now classified as “local,” it had … This attitude — that motor traffic should be funded nationally but that bicycle traffic should be funded locally — persisted. It was an attitude still very much to the fore at the launch of Britain’s first-ever National Cycling Strategy on 10 July 1996. Deep in the bowels of the Department for Transport building on Horseferry Road, London (and, yes, I was there) the then transport minister Steven Norris told the great and good of cycling that the Tory government would set targets to double cycling trips by 2002, and to double them again by 2012. Zero cash was provided to reach these targets because cycling was deemed to be “local transport” so local authorities should pay for any and all cycling infrastructure and promotions. The targets were dropped in 2004.