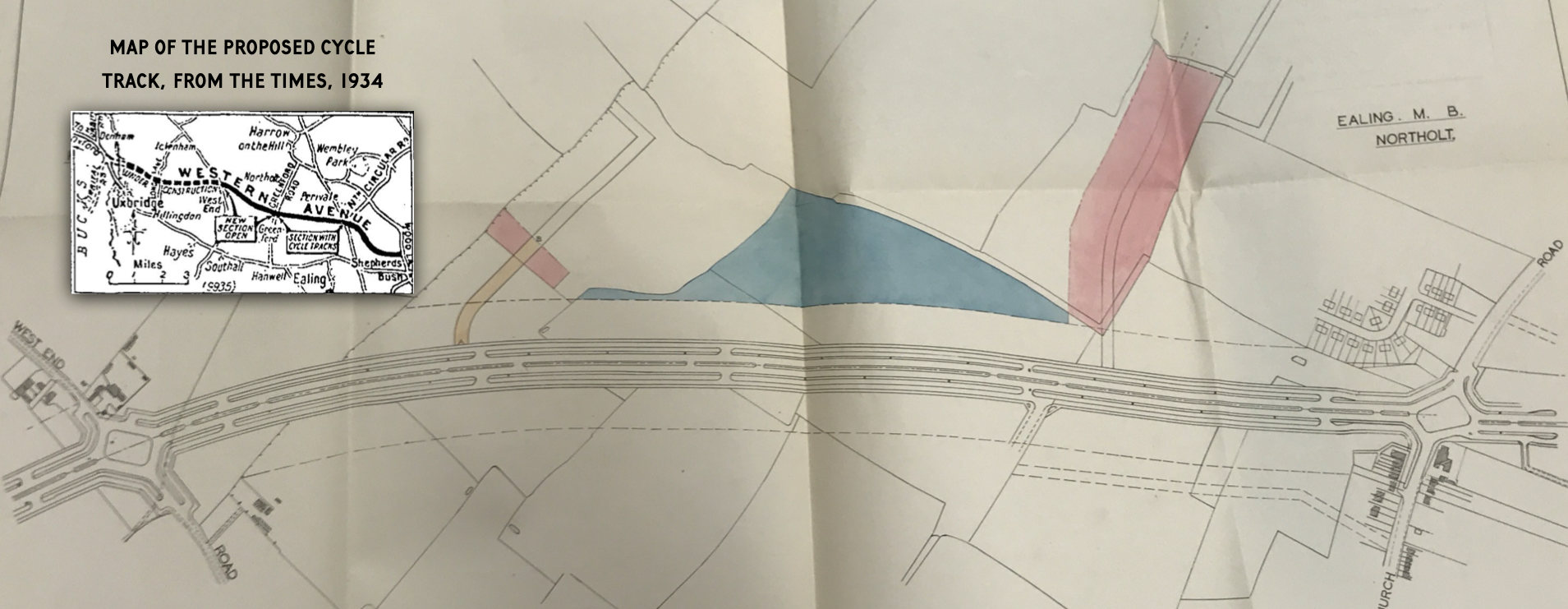

The Western Avenue cycle track was the UK’s first. The two-and-a-quarter-mile stretch of uneven concrete from Hangar Lane to Greenford Road in Ealing, London, kept separate from, but adjoining the new arterial Western Avenue, was commissioned in 1934 by Colonel Bressey, the Ministry of Transport’s chief engineer working to a brief from the Transport Secretary Oliver Stanley. (Subsequent Transport Secretaries Leslie Hore-Belisha and Leslie Burgin carried on the work started by Stanley.)

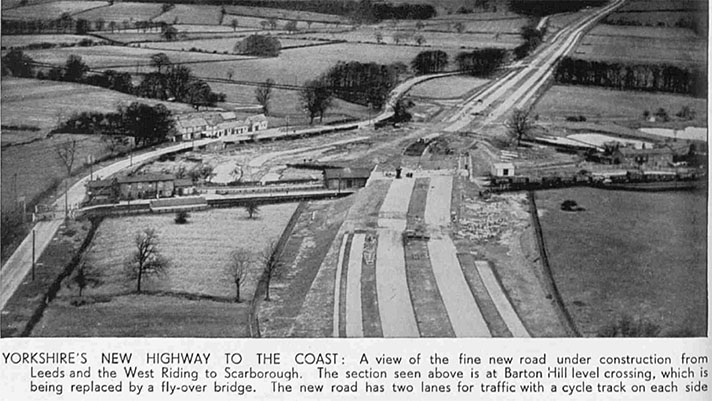

Photo of the Amsterdam–Haarlaem road which appeared in The Times in February 1934 and which the Ministry of Transport forwarded to its Dutch equivalent asking for plans.

In February 1934, a photograph of a Dutch cycle track, published in The Times, prompted Bressey to contact the Dutch infrastructure ministry (Rijkswaterstaat) director to ask him about the wide cycle tracks built beside several new arterial roads in the Netherlands. W. G. C. Gelinck responded with plans, maps, and other advice, all in English.

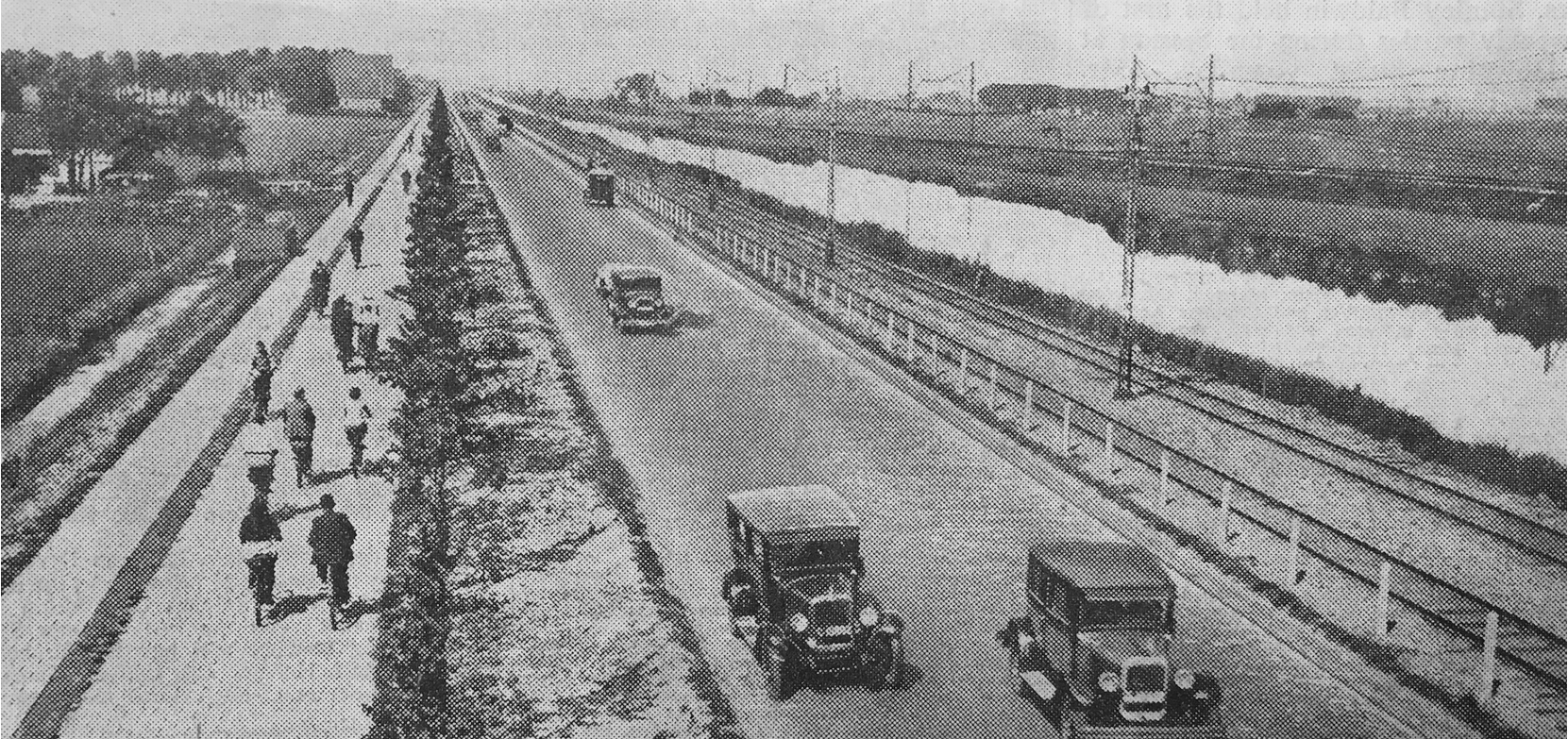

Britain’s first cycle track, 1934. The high-wheel rider is Oliver Dietrich.

Working from these plans Bressey commissioned the first cycle track, built by summer 1934, and which was opened officially in winter 1934 by new Transport Secretary Hore-Belisha.

Bressey’s plan was approved by Middlesex County Council on 26 April 1934. Very little, if any, of the original cycle track remains. Extensive remodelling of Western Avenue — including widenings and the addition of flyovers — has destroyed this innovative-for-the-time infrastructure.

Called a “new departure in traffic control” by the Daily Mirror the tracks were operational by May 1934.

A brochure produced for the official opening on 14 December of that year puffed: “For workers traveling between their homes and the factory, for children proceeding to and from school, for holiday-makers intent on a country jaunt, these tracks should prove a boon and a safeguard.”

A voiceover on British Pathé cinema news said the Western Avenue cycle track was a “new safety innovation” and that “motorist users of the road will be appreciative of this new boon.”

Sir F. C. Cook, MoT’s chief engineer.

Hore-Belisha, speaking at a luncheon at Wembley Stadium after the ceremonies were over, said that the “two cycling tracks which had been provided gave effect for the first time to the principle that classes of traffic should be segregated in accordance with the speed at which they could travel,” reported The Times.

The original 8ft 6in cycle track was made with inferior materials, admitted the Ministry of Transport. Later, wider ones elsewhere in the UK would be made with better materials, but the MoT could never escape criticism from cycling organisations who never forgot the botching of the first one.

Sir F.C. Cook, chief engineer Roads Department, Ministry of War Transport, wrote in 1941:

[The tracks] were formed in concrete and the edges of the transverse joints of the slabs have broken away, thus impairing their riding qualities … I am afraid that these old tracks, even when the joints have been repaired, will not furnish a running surface as smooth as those which have since been constructed as the result of later experience.

According to The Scotsman, the Western Avenue was divided thus: “Two one-way roads separated by a verge. Two one-way cycling tracks of white concrete. Two pedestrian paths.”

The newspaper added: “The cyclists’ tracks are to be placed on what would normally be the grass verge at the side of the highway. They will be separated from the kerb by a sloping path of macadam, the dark colour of which will warn them at night that they must not wander towards the road.”

Western Avenue plan, 1934. Inset: Map from The Times, 1934.

Cycling organisations were opposed to the new cycling track, and many cyclists refused to ride on it. One of these refuseniks was George Willison of Shepherds Bush who caught the attention of motorist Alfred Schroeder of Harrow who pulled up beside Willison and two companions as they were riding on Western Avenue’s carriageway rather than the cycle track.

“Schroeder pulled up and told them to get on the cycle track,” reported a newspaper.

“He stopped further down the road, and just as the cyclists were about to overtake them he re-started and pulled out towards the middle of the road, forcing the cyclists with him. A car coming from behind had to swing to the offside to avoid knocking down the cyclists.”

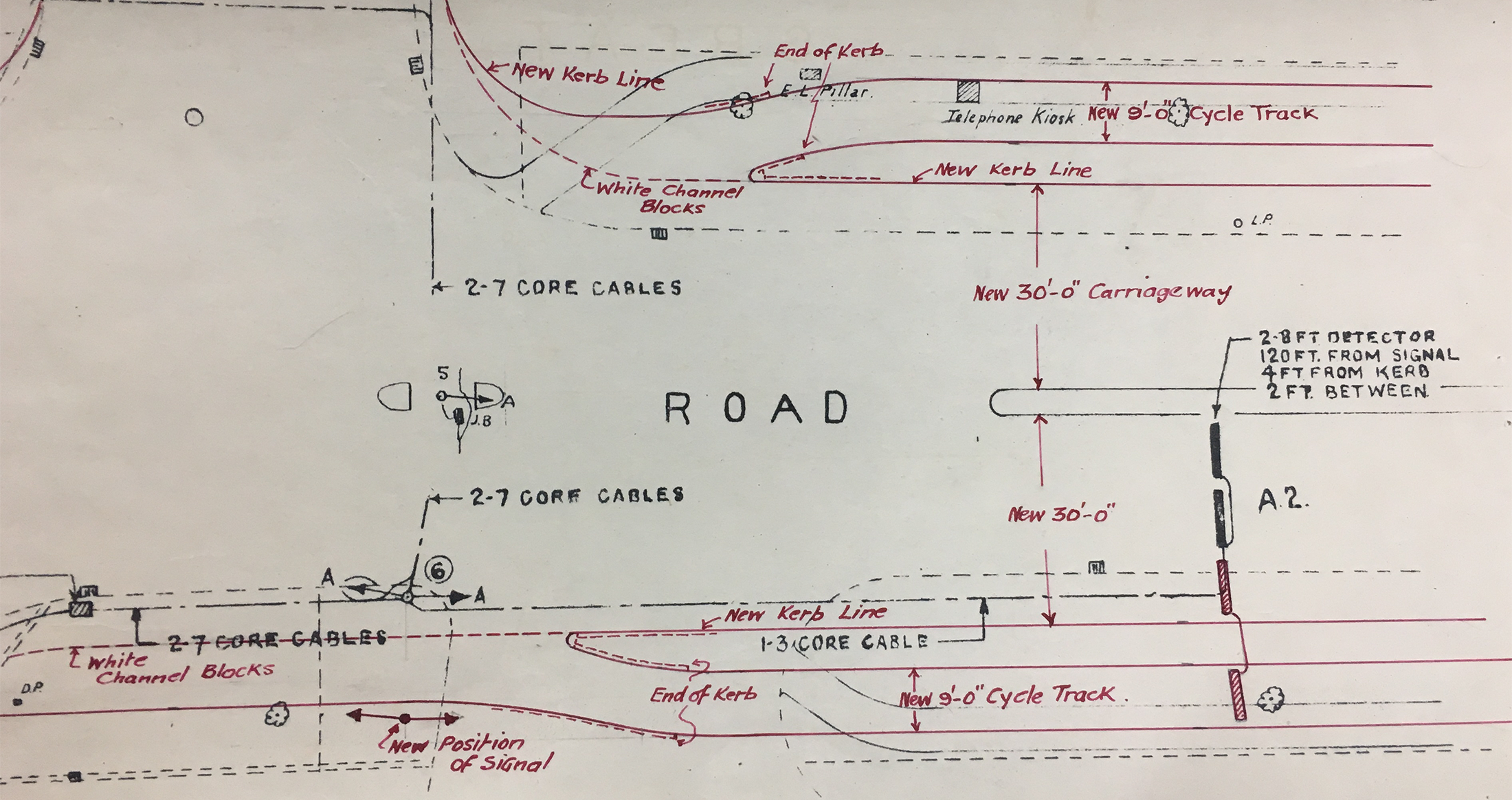

A 1936 MoT plan showing proposals for the extension of 9ft-wide cycle tracks on London’s Great West Road.

H. C. Hogbin, chairman of Ealing magistrates — and very possibly a motorist himself — couldn’t fathom why Willison and his friends didn’t avail themselves of the cycle track.

“The Bench wishes it to go forth that it is unsporting of cyclists when they don’t use the cycle tracks provided for them by the public authorities,” he complained, refusing to sanction Schroeder.

Earlier, motorist Pamela Laycon of South Hill Avenue, Harrow, took the law into her own hands. She “drove along the cycle tracks on Western Avenue, Greenford as a protest against the refusal of cyclists to use them,” reported the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer in October 1935.

“I thought I would retaliate on behalf of motorists,” she told the newspaper.

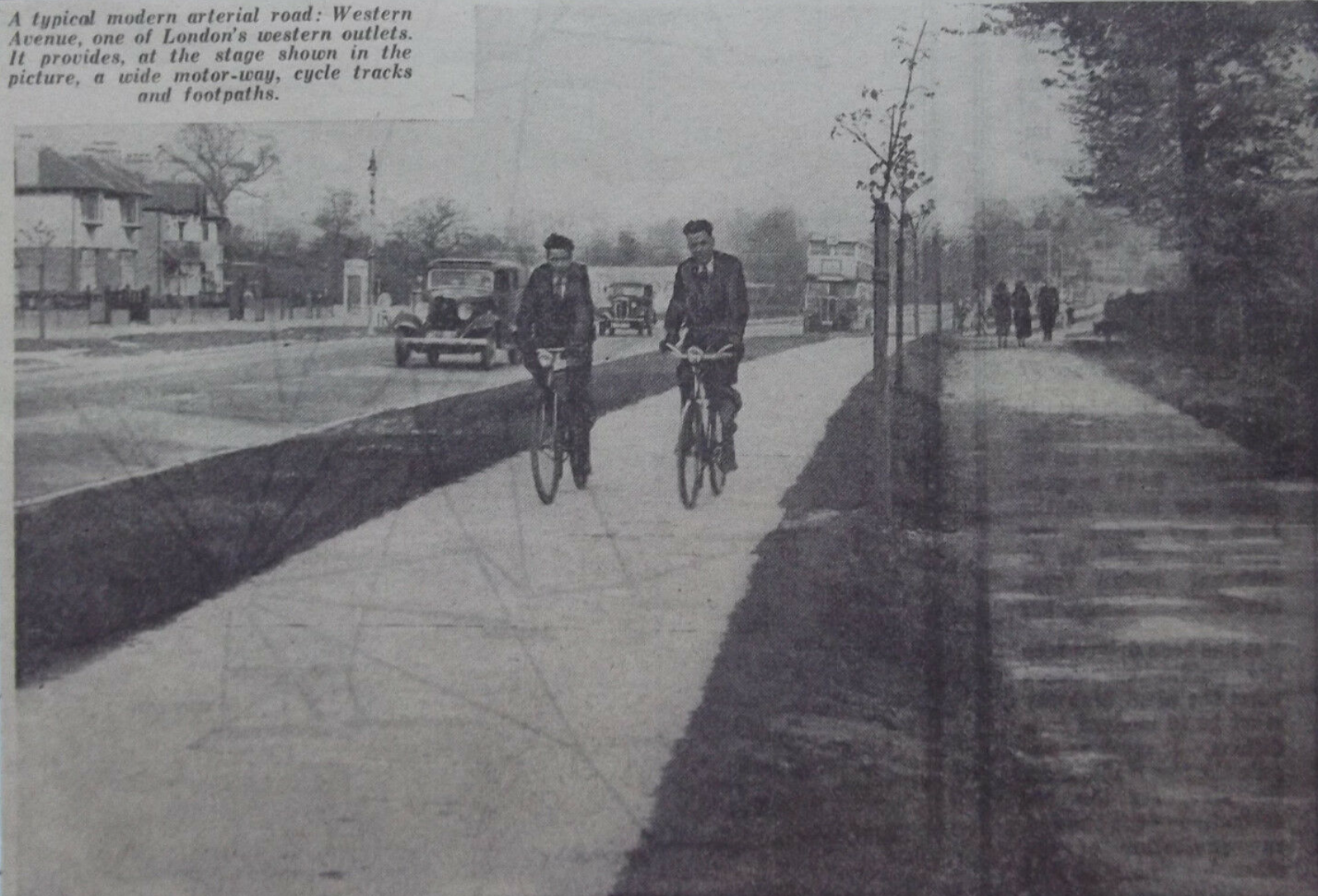

“A typical modern arterial road: Western Avenue, one of London’s western outlets. It provides, at the stage shown in the picture, a wide motor-way, cycle tracks and footpaths.”

“I drove down the cycle tracks at about 15 miles an hour, and when the police stopped me they said I would be summoned for driving dangerously, negligently, and without reasonable care.”

The police decided not to charge her.

“Now I have received a letter from the Commissioner of Police stating that I am not to be summoned, I must confess I am rather disappointed because my whole object was to get the motorists’ point of view ventilated,” Miss Layton explained.

Western Avenue’s cycle track was resurfaced soon after it was opened, and it was later extended, too.

“West London Middlesex County Council is calling for tenders for … the construction of cycle tracks on Western-avenue between the Great Western Railway at Greenford and Oldfield-lane, a distance of five-eights of a mile,” reported a newspaper in 1938.

The original cycle track between Hangar Lane to Greenford Road was much remodelled, even in the 1930s. The Tatler reported in 1939 that “a cycle track is being pulled up” on Western Avenue.