Cycle tracks on Great West Road at Osterley, London, 1937. Credit: Historic England archive, Historic England

A 1937 photograph taken from a long gone footbridge outside Osterley station in north London shows the Great West Road soon after it was widened and fitted with cycle tracks and footways. A cargo trike rider is on the road as are four other cyclists but there are also many cyclists using the cycle tracks, which fade into the distance. Steel fencing is visible on one side of the road, separating people on cycles from pedestrians.

Surprisingly little has changed in the intervening years. Trees and bushes have grown but art-deco houses on the right of the photo are still there, and the cycle tracks are still there along with the adjoining footways. The steel fencing has gone, now replaced with Armco motorway-style barriers to keep motor vehicles away from soft, squishy humans.

Great West Road’s cycle tracks at Osterley today.

The Great West Road (often styled as GWR) between Chiswick High Road and Bedfont was opened by King George V on 30 May 1925. Large swathes of land on either side of the 120-ft road were left untouched, ready for later remodelling. Into this space were added wide footways and cycle tracks. These were opened for use in May 1937, confirmed the Minister of Transport Leslie Burgin. A year earlier the previous Minister for Transport Leslie Hore-Belisha had made a Road Fund grant of £14,000 for the installation of five miles of track between Gunnersbury Avenue, Chiswick to Bath Road, Hounslow West.

“The County Council and the Minister of Transport himself are anxious to see these cycle tracks installed,” said a 1936 MoT memo, “and it is urgent therefore, that a grant be issued without delay, and the works proceeded with.”

The construction tender was won by Fitzpatrick & Sons, a London civil engineering firm founded in 1921. The company advertised its work on a sign seen in the above photo.

(The truncated post beside the hoarding is still there. It’s an old “stink post” which vented sewer gasses from beneath the footway.)

According to a letter sent from the Ministry of Transport to the American Embassy in 1937 the cycle tracks on the Great West Road were 6ft wide and extended for 8,976 yards, that is, just over five miles (8.2kms). However, some stretches of the cycle tracks were 9-ft-wide, said a MoT circular.

While the scene at Osterley station has changed little, the scene at Gunnersbury Avenue, close to where the cycle tracks started, was transformed out of all recognition by the opening, in 1964, of the Chiswick flyover and what became the M4 motorway.

The 1930s cycle tracks are still in situ — although their utility has been much reduced — on the Great West Road’s “Golden mile,” a corridor of often American-owned factories and showrooms, which lined the margins of the road, many of them in the Art Deco style.

There were showrooms for American cars from Hudson-Essex, Lincoln and Packard, and a Firestone tyre factory. There was a Gillette factory and a Coty Cosmetics factory, too.

Bicycles and electrical goods were marketed from the Currys building which, as well as losing its apostrophe, relocated its HQ to Great West Road in 1936. The British company, founded in Leicester in 1884, manufactured its goods around the UK; the white, modernist building on the “Golden mile” was a showroom, offices and warehouse.

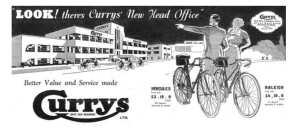

Advert for Currys in The Cyclist magazine, 1936.

“[Nowhere] in the whole of the British Isles is there a road which will advertise Currys to the world as the Great West Road,” boasted the company’s in-house magazine.

“The Directors are to be commended upon this wise choice of site for our Headquarters,” applauded the staff publication distributed to 200 Currys stores across the UK.

This internal love-in was joined by a public-facing promo when the building became part of Currys’ marketing. A line-art advert placed in The Cyclist magazine imagined the HQ as an attraction in its own right — a well-dressed male cyclist was illustrated pointing to his female companion, exclaiming, in awe, “Look, there’s Currys’ new head office.”

The cycle track played a starring but artistically misleading role in the advert, with six cyclists shown riding in front of the building. Misleading because the cyclists were shown riding bi-directionally while the cycle track was designed to be ridden in one direction only.

Prior to its completion, Middlesex County Council proposed to separate GWR’s cycle track from the footpath with a 9-inch strip of tar paving. This was “not thought to be satisfactory” wrote the MoT’s deputy chief engineer

R. J. Samuel, to London’s divisional road engineer on 10 August 1936. Instead, suggested Samuel, “it would be preferable to construct the cycle track 3” to 3.5” below the level of the footpath and to provide a kerb at the edge of the path.”

This, however, would increase the cost by £6,165 over the original estimate of £12,722, replied London’s divisional engineer, and would also delay the project.

“Whilst it would be possible for the work on the original scheme to be commenced within a week, yet if we insist on the proposed alterations it is unlikely that any work could be commenced until January next,” pointed out Mr. J. Rowland Hill on 28 August.

Replying on 3 September, Samuel came up with a compromise.

“In view of the urgency of this work for which this Department has been pressing for some time, I do not think that we can contemplate delaying its commencement until January,” he wrote.

Instead, he suggested the cycle track and footpath could be “separated by a bull-nose kerb with drainage apertures.”

He also asked for “colouring matter to be incorporated in the concrete for the cycle track so that the colour is distinctly different from the footpath.”

Fanatical cycle tourist John Sowerby — who loved riding on London’s arterial roads and eschewed their adjacent cycle tracks — wrote in his diary, published in 1939, that the GWR’s cycle tracks in 1938 were tinted with red pigment. He called them “pink atrocities.”

However, this might not have been the colour on all parts of the track for in the MoT archives it’s stated that, back in 1936, the Middlesex county surveyor used a cement described in a memo as “buff.” The cost of this colouration was £1,200 and “as soon as the ministry’s consent to this extra cost is given [the surveyor] will instruct the contractors to commence work.”

The consent — in the form of a cash payment — came on 30 September. Work therefore probably started on the works in October 1936 and were completed in June 1937. The cash payment was part of a 75 percent grant to install the cycle tracks.

Originally constructed by Middlesex County Council at a width of 6ft wide — against the initial wishes of the MoT which had requested 9ft-wide cycle tracks — the council, in October 1937, “prepared a comprehensive scheme for widening the carriageway to 30’ demolishing the existing cycle tracks and providing new ones 9’0” wide. The scheme also provides for the modification of the layout at junctions. These will result in the trees having to be removed.”

Two 9ft cycle tracks were subsequently provided, with two 10ft footways also as well as 6ft verges between carriageways and the cycle tracks. (It’s possible that these upgraded tracks were coloured pink, as per Sowerby’s tart observation.)

The new scheme cost £90,000 with the county engineer advertising for tenders on 21 October 1937.