“PERFECT MESS FOR MILES”/” REAL PLEASURE TO USE”

Period sources offer conflicting figures for the total length of British cycle tracks constructed between 1934 and 1945. The Ministry of Transport claimed to have provided grants to local authorities to build 500 miles of tracks. Critics claimed, wrongly, that just a handful of these were built.

Local authorities appear to have constructed more tracks than are noted in the official national record, including stats given as parliamentary answers by transport ministers of the day. Even those cyclists who were bitterly opposed to the tracks didn’t seem to know the full extent of the cycle tracks that they despised.

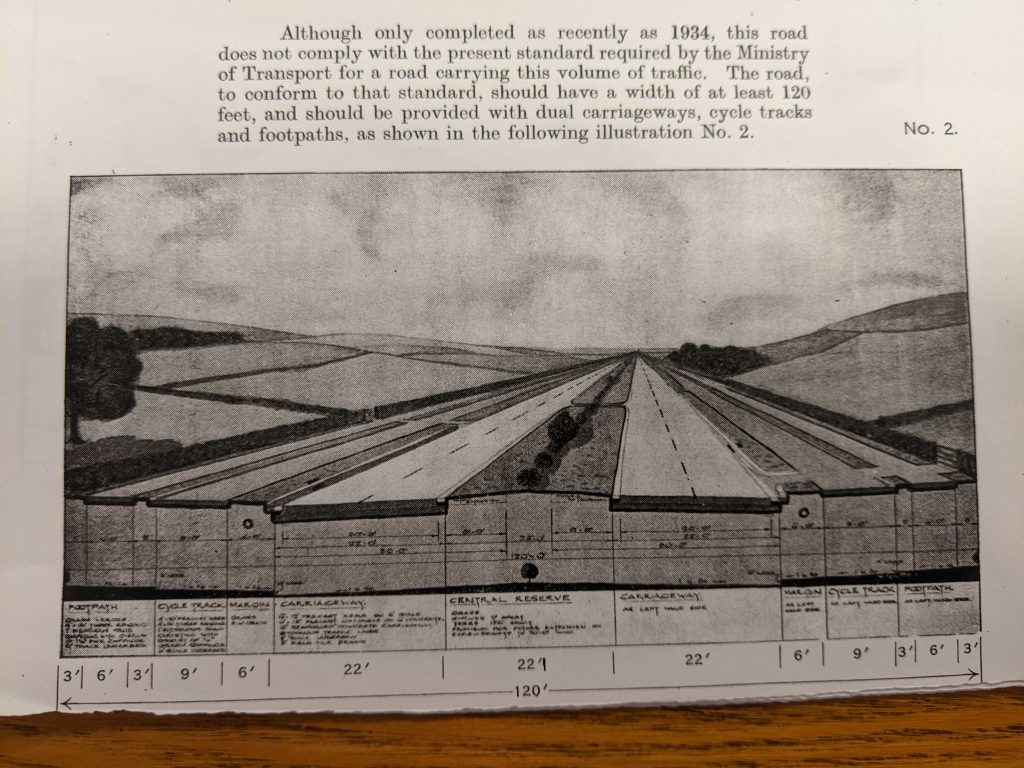

“Proposals have been made by highway authorities under the five-year programme for 230 miles of cycle tracks and 750 miles of dual carriage-ways,” transport minister Leslie Hore-Belisha told Parliament on 4th March 1936.

Speaking at a London meeting of the Commercial Motor Users’ Association twenty-two days later, Hore-Belisha said the government’s five-year road-building plan involved the construction of “nearly 500 miles of cycle tracks.”

The following year, Captain Austin Hudson, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Transport, told Parliament the plan was for “about 500 single track miles in Great Britain, including about seven miles in Scotland.”

According to Hudson, there were already “137 miles in England and Wales constructed or under construction and ¾ mile in Scotland.”

The Road Fund Report for 1937-38 stated that there were 189 miles of dual carriageways in Great Britain, with an additional 90 miles under construction. The report also stated there were 38 miles of cycle tracks in existence, with a further 55 miles being added. This equals 93 miles.

In 1954, the British Road Federation estimated there was 112 miles of cycle track in the UK, and 60,000 miles of roads. In the same year, the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation told Parliament there were 162 miles of cycle tracks. Two years later, an official government report on children’s cycling said there were 180 miles of British cycle tracks.

Based on on-the-ground plotting this research project estimates that at least 191 miles of cycle tracks existed by the 1950s, spread over 102 separate schemes. (Nearly 140 other road schemes, mentioned in period newspapers as soon to be built with cycle tracks, have been ruled out as either unbuilt or unproven.)

TYPICAL DESIGNS

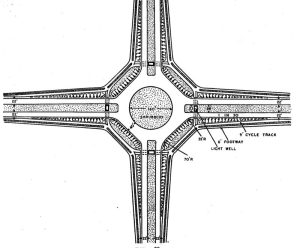

The period cycle tracks were mostly 9 feet wide, although a few were 6 feet wide. Two period cycle tracks on Teeside for iron foundry and chemical plant workers were 10 and 12 feet wide respectively. Most cycle tracks were originally surfaced with concrete, sometimes tinted with red or green pigments. Road surfaces were also usually made of the same grade of concrete, and only later were they capped with asphalt. Many period cycle tracks retain their concrete surfaces today and look incongruous next to asphalt surfaces.

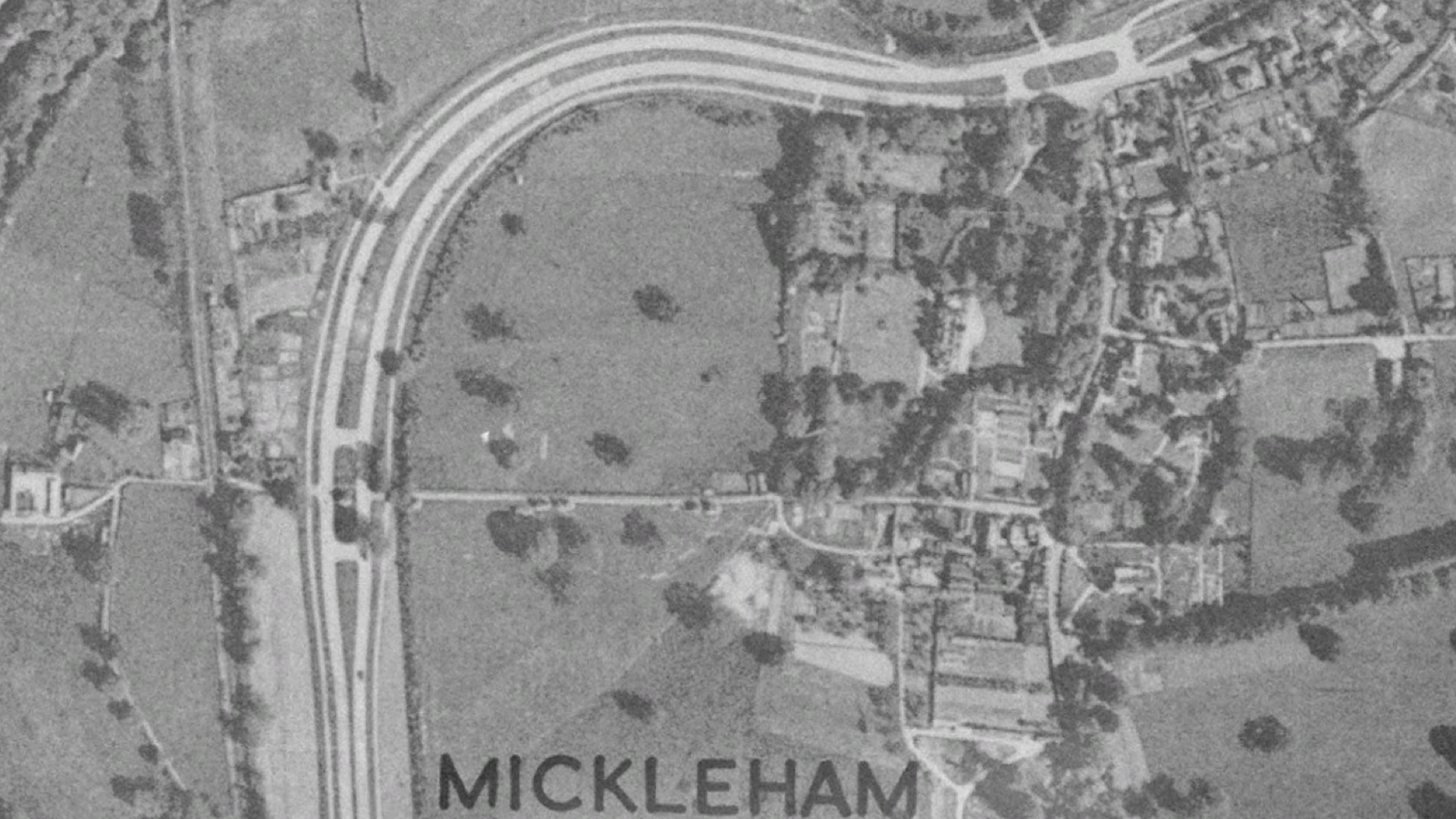

Concrete cycle tracks and roads appear as bright white lines in period aerial photographs.

The cycle tracks were typically constructed on both sides of the road, usually arterial ones, and most also had adjacent 6-ft footways. Today, even where the cycle track survives, many of the footways have disappeared but can sometimes be found beneath grass.

The best period cycle tracks were kerb-protected on the straights and had splayed entrance and exit points before junctions. The kerbs could be shallow or deep.

Typically, the cycle track was separated from the main carriageway by a wide grass verge, and a narrower grass verge similarly separated the cycle track from the footway.

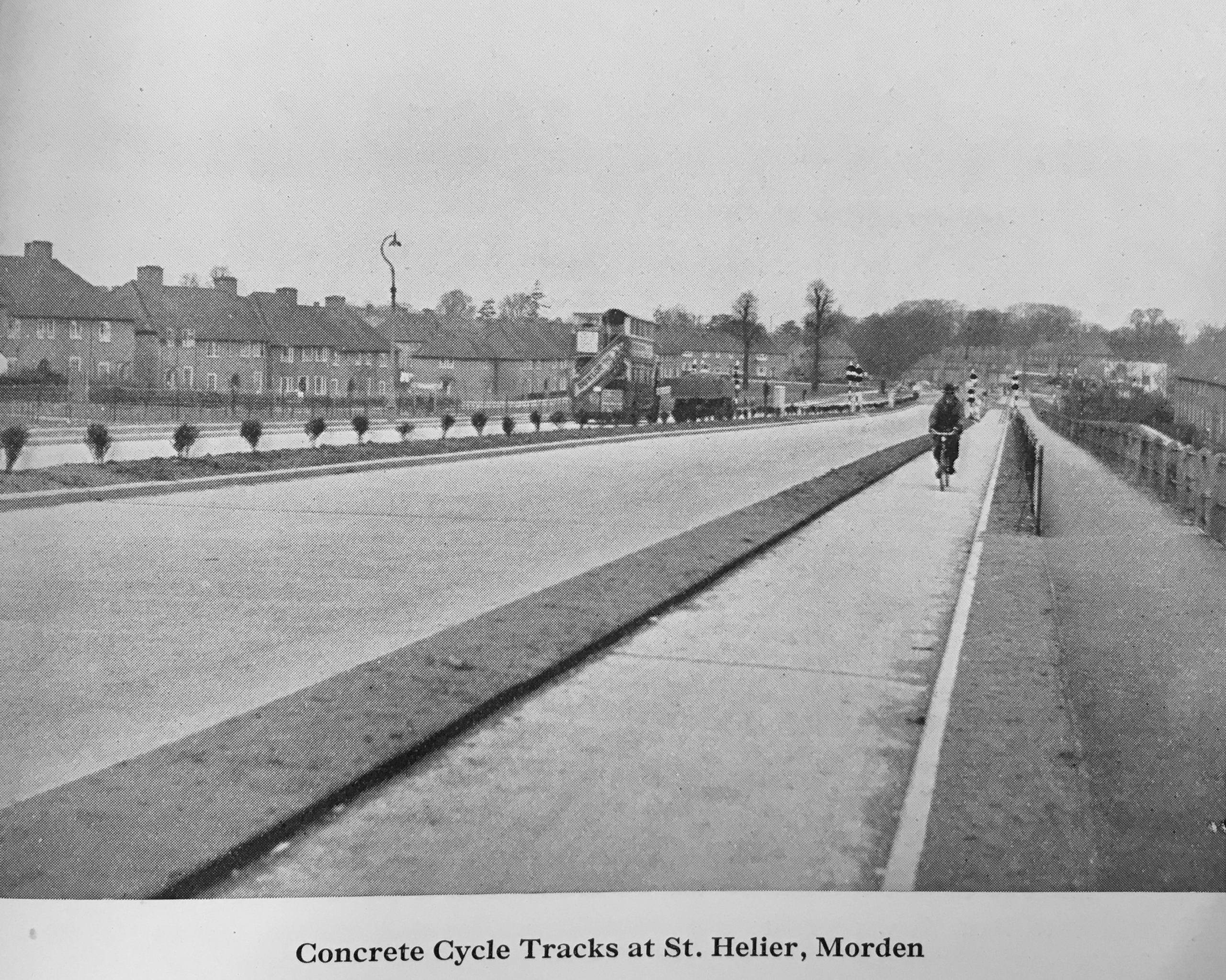

In some intra-urban examples — such as through the St Helier estate in London — the cycle track was separated from the footway by a wire fence, meaning pedestrians would have long walks to reach designated crossing points. (It’s likely such fencing was soon trampled down.)

HOW GOOD WERE THE 1930s CYCLE TRACKS?

Britain’s first cycle track was botched, and its poor quality gave all subsequent cycle tracks — often wider and built to higher standards — a bad name. Swiftly constructed in the summer of 1934 on a two-and-a-quarter-mile stretch of London’s Western Avenue, the experimental 8ft 6in cycle track was made with inferior materials, admitted the government several years later.

Writing in 1941, Sir F.C. Cook, chief road engineer at the Ministry of War Transport, disclosed internally that the “edges of the transverse joints of the slabs [on the first cycle tracks] have broken away, thus impairing their riding qualities.”

“I am afraid,” he told ministers, “that these old tracks, even when the joints have been repaired, will not furnish a running surface as smooth as those which have since been constructed as the result of later experience.”

Western Avenue’s cycle track was resurfaced soon after it was opened, but its narrow rutted surface was ammunition for cycling organisation officials who had predicted, some months before the first concrete had been laid, that the “tracks would not be kept in reasonable and comfortable condition for cycling.”

Many of the cycle tracks built after the first few experimental ones were constructed to higher standards, but, in their numerous complaints over several years, cycling officials always harked back to the shoddily built first ones.

“I set sail up the Great West Road to find it a perfect mess for miles with new cycle paths being made,” wrote cycling diarist John Sowerby in 1938.

“Those pink paths had a surface like a rubbish heap, cement full of cracks and pot-holes,” he continued. “No wonder that few cyclists used them.”

That cyclists wouldn’t care for a poor riding surface should not have come as a surprise — the National Cyclists’ Union and the Cyclists’ Touring Club had been lobbying for better road surfaces since they co-founded the Roads Improvement Association in 1886, several years before the advent of motoring in Britain.

The Conservative MP for Henley addressed the then minister of transport in Parliament and emphasized the need for a good quality running surface. Sir Gifford Fox said it would be pointless to enforce the use of cycle tracks if they were poorly surfaced.

“At the present time there is no [compulsion for] cyclists to use these tracks,” said Fox in July 1937.

“The only way to encourage them to do so is to see that the cycle tracks have a good smooth surface so that it is easy for the cyclists to pedal along them.”

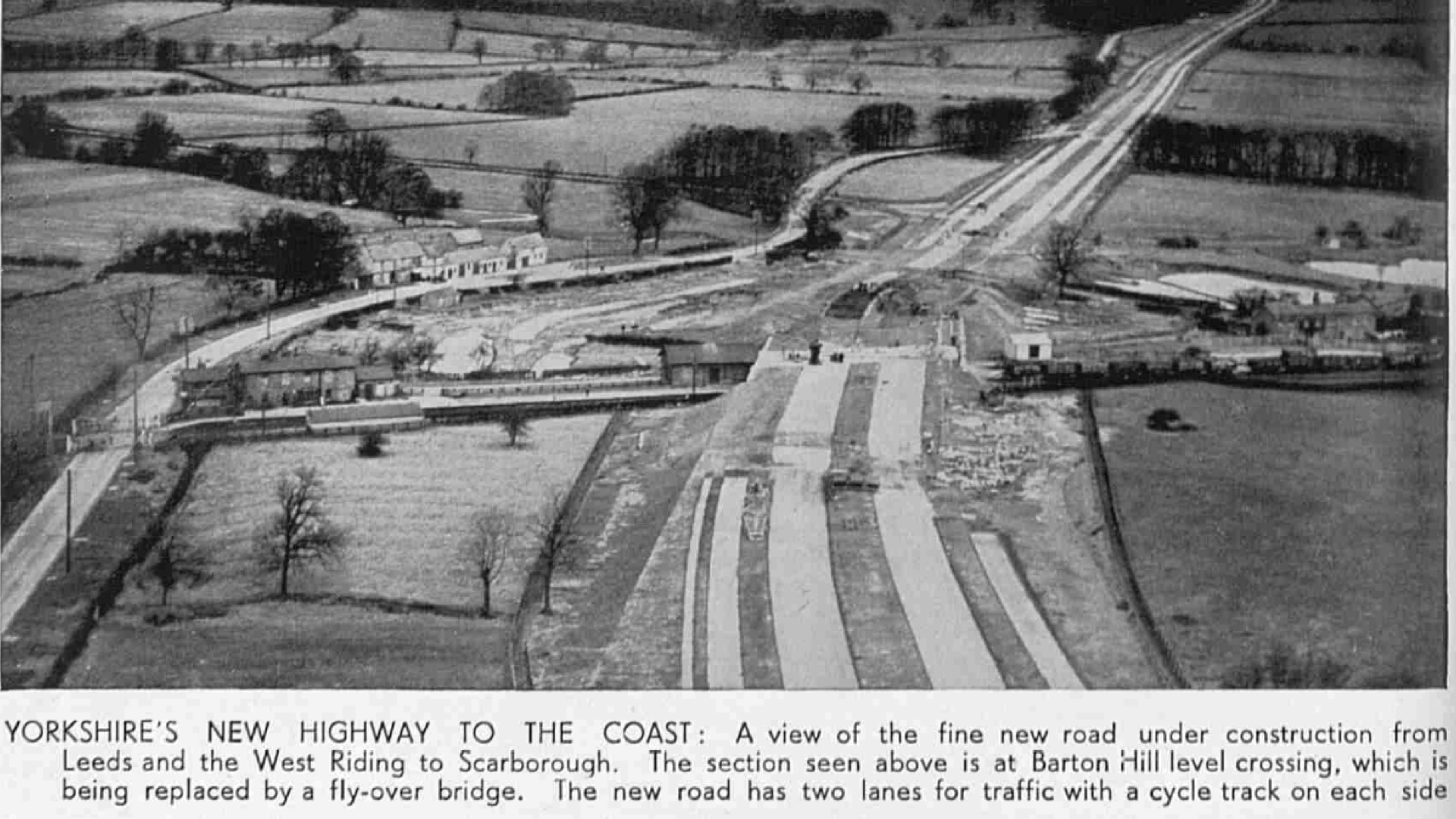

In 1937, a Yorkshire Evening Post journalist took to his bike and reported on the surface of the new cycle tracks beside the A64 near York.

“A motor road view of the cycle path undoubtedly will make it hard for motorists to understand why some cyclists have raised opposition to them,” he conjectured, “but [the] appearance of billiard-table smoothness is not borne out by trial. Already there is a slight but distinct ‘waviness’ of the surface, while the skin of the surface is broken in places. These defects, at the moment, are extremely trifling, but as they cannot be put down to wear and tear by bicycle wheels, it is a reasonable deduction that frost and snow will further crack and hump the path, which is less solidly built than the motor road.”

ROAD RESEARCH LABORATORY

In 1938, the Ministry of Transport commissioned surfacing tests on several cycle tracks, including a long-term trial by the ministry’s Road Research Laboratory on the A198 at the Scottish village of Longniddry, 14 miles south of Edinburgh. (There were also surfacing tests on the Colnbrook bypass in London, close to the Road Research Laboratory HQ.)

The Longniddry tracks were divided into zones, with different surfaces for each zone — for example, thick or thin concrete or concrete with an asphalt top layer. The surfacing materials were probably to be checked after a year of use, but the outbreak of WWII halted the evaluation.

In 1946, the Road Research Laboratory returned to the tracks. Working with the Cement and Concrete Association, the MoT examined how each of the surface treatments had fared in the intervening years.

The survey provided a plan of the tracks in 1946. They were 6 ft wide and separated from the road by 3 ft of grass and a kerb. A 6 ft sward of grass separated the cycle track from a 6-ft-wide footpath surfaced with ash. (Today, the footpath is buried.)

The cycle track was “divided up into 5 lengths of different types of construction … [of at least 600 ft each],” said the 1946 survey. One was a 3-inch-thick of unreinforced concrete; another was a 2-inch-thick of reinforced concrete, and a third was concrete covered with an “asphalt carpet.”

According to the survey, the “sections are numbered 1 to 5 starting at the East end of the track nearest Longniddry and working westwards towards Edinburgh.”

Cyclists don’t tend to damage road surfaces with their passing. “The general appearance of the all-concrete length is much the same as when the job was finished,” stated the survey.

“There is no evidence of wear nor are there any defective sections,” the examination concluded.

The concrete had been damaged neither by heat nor cold. “There is only one contraction crack and that is in a 2.5 inch thick reinforced slab,” reported the survey.

Most of the 1930s cycle tracks were separated from the main carriageway by kerbs, and some firms made a great deal of money by specialising in manufacturing such items for local authorities. The concrete kerbs used on the Raynesway in Derby were made by Sawley Kastone, a company formed in October 1936 “for the manufacture of concrete products.” According to a 1938 newspaper profile, Sawley Kastone was “primarily directed to the manufacture of kerbs, slabs, and the main requisites … for new by-pass roads and cycle tracks embodying concrete edging.” The company, reported the newspaper, was responsible for the “manufacture of approximately seven miles of kerb (buff and grey) for the new by-pass road from Alvaston to Spondon.”

According to a reporter for the Coventry Herald in November 1939, the cycle tracks adjacent to the Coventry bypass were “wide enough for three to cycle abreast, and for two to pass comfortably.” The reporter added: “The surface is good, and the dips into the highway at junctions, are smoothly finished off.”

PEDESTRIANS

Grass strips usually separated cyclists and pedestrians on 1930s cycle tracks, and there were many complaints from cyclists of pedestrians “encroaching” on the infrastructure meant for cyclists alone. Had the cycle tracks been made wider, it’s likely pedestrians would still have used cycle tracks, and the relatively narrow width of the period infrastructure was often a bone of contention with organised cycling, as predicted by Wright Miller of Putney, London, who wrote to the Ministry of Transport in 1927 suggesting the building of cycle tracks up to 12 feet wide.

Wright Miller — self-described as a long-time cyclist and “for many years Public Inspector of Roads and Buildings” — wrote to the MoT’s chief engineer, Colonel Bressey, to “enlist [his] influence in the construction of special paths for cyclists along all our public roads … I suggest that along one side of all our roads, a path say ten to twelve feet wide be constructed, preferably of reinforced concrete …”

Predicting opposition to such cycle paths from cycling organisations, Wright Miller added that cyclists “are opposed to the suggestion of special paths for their use, as they fear that such paths would often be merely narrow mud paths, inferior in every way for cycling on to our present carriageways; but provided that the paths be constructed as suggested, cyclists would be only too glad to make use of them.”

Bressey did not take Wright Miller’s idea seriously at the time, but when, in 1934, the MoT’s chief engineer was instructed to evaluate the cycle tracks of the Netherlands, and this was communicated in the press, Wright Miller wrote again in February of that year.

“As a cyclist of over 40 years’ extensive experience both in England and abroad I am very glad to see that you are proposing at last to make use of the admirable opportunity of constructing special cycling-paths,” wrote Wright Miller, adding that:

… if such paths are going to be of real use … I would very strongly urge the absolute necessity for making the proposed paths not only permanently superior as regards surface for cycling on, compared of with even the best present-day road-surfaces, but sufficient width to cope with the ever-growing number of cyclists … I would suggest therefore that the proposed paths should be at least wide enough for not less than 4 lines of cyclists to pass each other with comfort …To provide cycle paths of a width for four lines of bicycles may at first seem excessive, but cyclists are about five times more numerous than motorists …

When it became clear that the MoT had settled on 9-ft as the maximum width for cycle tracks Wright Miller wrote again on 9th June: “I am sorry to see the proposed cycle paths are to be only 9ft wide,” he communicated.

“I speak not only from a practical experience of road-making, but from 50 years’ experience in cycling and travelling in a dozen different countries, including every county and corner of my native England. I hope you will remedy this very obvious defect in the proposed cycle-paths; then you may hope to see them used. Otherwise the idea will not succeed, and the money spent will be wasted.”

Many others voiced similar concerns. As recounted elsewhere in this study, Eric Claxton, the designer of Stevenage’s 1950s cycleways, was a critic of the 1930s cycle tracks. He was a junior engineer in the Ministry of Transport in the 1930s, and he wrote in the 1970s that the cycle tracks he worked on in London were substandard. “As a cyclist, they gave me no satisfaction,” he complained, adding that they …

… were too narrow. They were made of concrete and suffered from either cracking or construction joints. They provided protection where the carriageway was safe but discharged the cyclists into the maelstrom of main traffic where the system was most dangerous. For me worst of all the tracks were uni-directional either side of the dual carriageways; thus if for any reason one needed to retrace one’s way, one was compelled to run the gauntlet of crossing the streams of traffic on both carriageways to return on the far side — woe betide the person who left money, keys, books, tools or even lunch behind.

A Ministry of Transport report in 1944 stated that the opposition of some cyclists to cycle tracks was understandable and “does not arise from a spirit of obstinacy but is largely based on the inadequacy of the cycle tracks so far constructed and the dangers [to] which they give rise.”

Ten years later, Staffordshire County Council proposed to spend £10,000 on making its six and a half miles of trunk road cycle tracks “more attractive” to riders, reported a newspaper.

County surveyor Mr. F. J. Jepson suggested that the tracks should be adequately curved and drained, and surfaced with a fine-textured material that would give them equal, if not superior, riding qualities to those of the roads. “Without legislation to compel cyclists to use the tracks, the only means of extending their use would be to improve the standard so that cyclists prefer them,” he declared.

The trouble was that the “road surface is far superior to that on the tracks,” later explained the Staffordshire Country Council’s highway committee’s chairman. He said cycle tracks “were given only a rough tarmac.” (In fact, cycle tracks were usually surfaced with concrete, and later, roads were improved with smoother asphalt surfaces.)

“Even where the tracks are in good repair they present a number of hazards,” pointed out a parliamentary cycling safety report in 1956 including “unsatisfactory features” such as “they normally break off at junctions, which are the very points at which cyclists need protection, and, particularly in built-up areas they are used by pedestrians, intersected by driveways to houses and blocked by parked vehicles.”

Two years earlier, the PR officer for the British Cycle and Motor Cycle Manufacturers and Traders Union had sent a letter to The Times complaining about the lack of maintenance for the extant cycle tracks.

“It is an acknowledged fact,” Hilary Watts stated, “that a very high proportion has been allowed by the authorities to get into a complete state of disrepair and is quite unusable by cyclists.”

In 1961, L. Unwin, PR officer for the British Cycling Federation, told The Times that cycle tracks were by then unusable: “You see them now neglected, with grass growing in the cracks. Long stretches on the Southend road are unrideable.”

Sixteen years later, civil engineer and traffic engineer John Joseph Leeming wrote to The Times with a similar complaint.

“I was in charge of the work on the county section of the Oxford northern by-pass, which was opened in 1935,” remembered Leeming.

“On it we planned for bicycles by providing very expensive concrete cycle tracks on both sides of the road. A week ago I travelled over the road, and these tracks could just occasionally be seen through the grass which covered most of them. This is hardly encouraging to engineers to plan for cycles.”

CYCLE TRACK USAGE

Club cyclists and cycling organisations disparaged the 1930s cycle tracks and often pointedly didn’t use them. Still, period census after period census found that ordinary cyclists had no such qualms: the cycle tracks were well used.

A one-day MoT traffic census on the cycle tracks of Western Avenue, Ealing, a year after they were installed, found that of 1,172 cyclists only 47 rode on the main road.

“In other words, 96 percent kept to the experimental tracks,” reported the Daily Herald.

Earlier that year, in parliament, transport minister Leslie Hore-Belisha had said the proportion of cyclists using the tracks was 84 percent. “These are the wiser … section of the cyclists,” he snarked.

The cycle tracks were “most popular,” he confirmed two months later, and used “by the overwhelming majority.”

“Cyclists were last year in arms against cycle paths,” reported a Daily Herald correspondent in May 1936. “But they are using them. On Western-avenue … I counted 38 cyclists using the special tracks and two who were not. On St. Helier-avenue, near Morden, Surrey, a new double-track road that is nearly finished, I saw in half hour only one cyclist riding in the roadway and 43 who preferred to be safe on the special tracks.”

“Experience shows that where cycle tracks exist they are extremely popular, and the antagonistic attitude of cycling organizations does not seem to have had a very far-reaching effect,” Col. T. T. Tudsbery, southern divisional road engineer of the Ministry of Transport, told a road conference in Truro in 1936.

However, it depended on the track: because it was built to an inferior width of 6 ft rather than the more usual 9 ft, cyclist usage of the tracks on London’s Great West Road was not as high as on other tracks.

“Sunday 15th August: 1460 on the track, 2051 on the road. On Monday 16th August, 1049 on the track, 1303 on the road. Windmill Road. However, at Jersey Road 1187 on the track on Monday, and 816 on the road,” reported the MoT in 1937.

“A census of cycles using and not using the cycle tracks on Sunday 20th June show that 821 cyclists were using the tracks and 118 the dual carriageways,” reported Yorkshire’s county surveyor in 1937, citing usage on the A64 north of York.

“I think the results are encouraging,” stated the northern divisional road engineer to A. J. Lyddon, MoT’s deputy chief engineer, “and all we can expect from Yorkshiremen, as the road has only been open for one month.”

“A Yorkshire Evening Post reporter, a cyclist, yesterday traversed the new part of the York-Malton road,” revealed the newspaper in the summer of 1937.

“He rode upon the much-discussed cycle paths with which the new road is equipped. Below, he gives his impressions of this expedient for securing road safety:

Representations in black, on a white-enamelled background, of a very sedate roadster bicycle, with the words ‘Cyclists Only’ mark the points where the cycle paths diverge from the road.

The first user of the cycle path that I saw was a policeman who sailed majestically from the road into the mouth of the path and spread himself comfortably in the middle of its three yards width. The next bunch … was a double file bunch of about six singles and a tandem pair. They six singles swept by the entrance to the path, ignoring the invitation, and continued along the motor road. The tandem pair chose the track.

The rear quartet of cyclists, in 100 yards or so, sensed they had lost the tandem riders, and then spotted them on the cycle path. They apparently had not seen the path until then! They dismounted, crossed the grass verge to the path, and gave it a trial. The two leading cyclists continued to ignore the path, a procedure which deeply agitated about one in every 10 motorists, judging by the flourishing of arms from car windows as they passed.

A companion and I took to the path. Its width is generous — though perhaps not all cyclists will agree with this statement. At any rate, it is wider than many other cycle paths that have been laid down elsewhere and the two of us had ample room to ride abreast.

Anyhow, it was comfortable to ride along with the feeling that one’s safety was not in the hands of some motorist behind you.

Surveying the traffic coming up the hill from the direction of York, it was clear that about 80 per cent of cyclists were using the paths, notwithstanding the opposition that has been raised to them. Two lone riders, in single file, stuck to the road, in spite of waved admonitions from motorists to get on the path.

We turned off the cycle path to visit Kirkham. This involved going on the up motor track, riding it along for 100 yards or so to the opening to the down motor track, and a similar distance along this track before we could escape into the Kirkham Lane.

The crossing taught us that at road junctions like this, the cycle path ceases to be a complement of the entire road, and becomes, in effect, a minor road joining up with the motor road.

My conclusions regarding cycle paths are:

They afford a sense of freedom and safety to cyclists who wish or need to use busy highways like them. As one who regards riding on the roads not simply as a means to an end, but also in an end in itself, I am not interested in the York and Malton road any longer.

Presumably because of their lighter construction, they may deteriorate more quickly than the motorised part of the road.

Traffic coming on to the main road from side roads is liable to block the cycle path until it is able to move on to the motor road.

Care will have to be taken by cyclists at each end of a cycle track where it bring them — at an angle, of course — into the road used generally by all traffic. Single-file riding at these points, it seems, will be necessary to ensure safety.

Leeds Mercury journalist Frank Snape reported in 1939 that cyclists were “making good use” of the A64 cycle tracks:

I found during my run to the coast and back that both drivers and cyclists seem to be getting accustomed to the slightly different technique required on a modem dual carriageway with cycle tracks. The car driving was excellent, for people driving slowly were keeping well to the left and leaving ample room for fast traffic to overtake, and cyclists were making good use of their tracks. I was particularly struck by the attitude of the cyclists in view of the outcry their organisations so mistakenly raised when tracks were first proposed. All sorts of difficulties, most of which were imaginary, were raised, but on Saturday and Sunday hundreds of men and women were cycling happily and safely on the tracks, and I saw only one instance in my two journeys of a man preferring the rougher and more dangerous motor-way. I felt sure from the start that cyclists would use the tracks when they found how much smoother they were than the highway, which inevitably becomes a little rough and wavy through the hammering it receives from heavy traffic.

A Nottingham Evening Post reporter in 1939 noted:

“It was noticeable that, wherever there were cycle tracks, club members riding three or four abreast in groups of a dozen or two ignored them, but other cyclists, obviously out for a day’s run in numbers of four or five, stuck to them invariably.”

“Sober-minded” cyclists who wrote to The Times in 1935 welcoming tracks were likely more middle class than the usual riders who cycled on the tracks. Still, their support shows that opposition to the infrastructure provision was not universal among cyclists.

Maurice Evans of High Wycombe described himself as a regular user of the tracks on Western Avenue and said the “tracks have converted what was previously a nerve-racking [sic] ride into a care-free glide, except for occasional indiscreet pedestrians. I have no objection whatever to being ‘segregated’, and shall use tracks wherever I happen to travel, if they are kept up to the Western Avenue standard. I suggest this is the view of most sober-minded cyclists travelling to and from work.”

John Bearder of Halifax agreed:

There is a feeling now prevalent among British cyclists that if they were segregated they would suffer “a sort of insult”; since they maintain that they have as much right to use the highway as anyone else. To anyone who has cycled on the Continent this stubborn view appears to be not only fantastic but so unfavourable to the cyclists themselves. As one who has cycled a good deal in Germany I can honestly say that there is no comparison between cycling on the highway and cycling on these special cycle tracks. On these tracks cycling is a real pleasure; there are no motorists to hoot you and brush past you, the scenery can be admired without fear of death, and, above all, a somewhat elusive obstacle is removed from the highway.

NOTES

[1] Mr. HORE – BELISHA

Its first instalment—works approved for commencement during the current financial year—is estimated to cost £22,500,000 — 3½ times the figure at the corresponding period last year. In order that modern requirements may be fulfilled, higher grants have been offered for work on trunk roads and for the novel features of dual carriageways and cycle tracks.

That is visualised. The development of roads, like the growth of forests, is a long process, but progress is being made with perceptible rapidity, and as some indication of it I would mention that proposals have been made by highway authorities under the five-year programme for 230 miles of cycle tracks and 750 miles of dual carriage-ways.

HC Deb 04 March 1936 vol 309 cc1415-69

[2] Daily Herald, 26 March 1936

[3] Mr. Anstruther-Gray asked the Minister of Transport the number of miles of cycle tracks in England and Scotland, respectively?

Captain Hudson There are 137 miles in England and Wales constructed or under construction and ¾ mile in Scotland. The Five-years’ Programme contemplates the construction of about 500 single track miles in Great Britain, including about seven miles in SMr. Anstruther-Gray Will my hon. and gallant Friend take steps to see that Scotland gets a rather fairer share?

HC Deb 22 March 1937

[4] HL Deb 03 May 1939

[5] “Of this very small mileage it is an acknowledged fact that a very high proportion has been allowed by the authorities to get into a complete state of disrepair and is quite unusable by cyclists …

Cyclists generally are perfectly willing to use properly maintained cycle tracks provided they are not encumbered by prams and playing children etc.”

Letter in The Times by Hilary Watts, public relations officer, British Cycle and Motor Cycle Manufacturers and Traders Union.

The Times, December 21, 1954

[6] Lieut.-Colonel Bromley-Davenport asked the Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation if he will give the mileage of cycle tracks on trunk roads and classified roads, respectively.

Mr. Boyd-Carpenter: 112 miles on trunk roads and 50 miles on classified roads. 17th November, 1954. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/1954-11-17/debates/1415ab57-c593-4cdb-8ad7-a2eb3ee02c65/WrittenAnswers

[7] Report on Child Cyclists

MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND CIVIL AVIATION

COMMITTEE ON ROAD SAFETY

HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE

1956

Summary of principal recommendations

- We also recommend that : —

(a) existing cycle tracks should be improved and new tracks built but not

alongside new motor roads ; (para. 14, 16)

( b ) wherever it is practicable, consideration should be given to marking

lanes at the edges of the road and reserving their use to cyclists ;

(para. 14)

(c) special attention should be given to making the edges of all roads

suitable for cycling by providing smooth and uninterrupted surfaces ;

(para. 15)

The provision of cycle tracks to give some measure of segregation from

other vehicles has been recommended in the past and there is no doubt that

effective separation of cyclists, and child cyclists in particular, from faster

moving traffic would reduce the number of accidents. However, the provision

of cycle tracks is not a simple matter and it is particularly difficult in ‘ built-up ’

areas where accidents to child cyclists are most numerous and where probably

the majority of cycle mileage occurs. There are only about 180 miles of cycle

track in the United Kingdom and much is in a poor state of repair. Even

where the tracks are in good repair they present a number of hazards in that

they normally break off at junctions, which are the very points at which cyclists

need protection, and, particularly in ‘ built-up ’ areas they are used by pedes-

trians, intersected by driveways to houses and blocked by parked vehicles. It is

not surprising therefore that cycle tracks are regarded as a mixed blessing and

so long as they contain unsatisfactory features it would be unfair to suggest

compulsion for cyclists to use them. We consider that vigorous efforts should

be made to improve the standard of existing tracks and to reduce their unsatis-

factory features as far as possible.

The construction of new motor roads from which cyclists are excluded

should reduce congestion on existing roads and improve conditions for cyclists.

But the leisurely motorist may keep to existing roads and this type of motorist

is often, like the cyclist, dividing his concentration between driving and observing

his surroundings, particularly where the journey itself is a form of relaxation

and recreation. It may be unwise therefore to expect that a marked improve-

ment in safety of cyclists will be obtained through the construction of motor

roads and to the extent that they encourage more vehicle ownership and mileage

they may increase congestion and therefore the dangers to cyclists in the ‘ built-

up ’ areas. The number of long distance cyclists seems likely to diminish with

the growth of motor car and motor cycle ownership and since child cyclists

do not as a rule travel long distances we do not think the very great expense

that would be involved in providing proper cycle tracks alongside the motor

roads would be justified.

Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, Committee on Road Safety, Report on child cyclists, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1956. https://archive.org/details/op1265790-1001

[9] 7th January 1941. See: CYCLE TRACKS: Proposed construction, 1926-1943, Ministry of Transport, MT 39/127, National Archives, London.

[10] Nottingham Evening Post, 16 February 1934.

[11] John Sowerby was the nom de plume of Percival Bennett, author of the best-selling 1939 book “I Got On My Bicycle (Frederick Muller Ltd), a diary of his 40+ mile daily rides between 20th April to 17th October 1938, when he was 57.

[12] HC Deb 09 July 1937. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1937/jul/09/supply

[13] CYCLE TRACKS IN EAST LOTHIAN

The attached report, prepared by the Cement and Concrete Association describes the condition in March, 1946 of the cycle tracks laid in 1938 on the Edinburgh-North Berwick Road,

Date of inspection: 28th March 1946

Date of construction

September-October 1938.

Age at time of inspection: Almost 8 years.

Length: 3060 lin. ft.

Width: 6 ft.

Thickness of concrete and reinforcement

The total length of 3060 lin. ft. was divided up into 5 lengths of different types of construction, thus; Section No.1 (660 lin. ft.) 3 in. thick unreinforced 3 concrete.

Seotion No,2 (600 lin. ft.) 2½ in. do. do. do.

Section No.3 (600 lin. ft.) 2 in. thick concrete reinforced 1.5 lb. sa.yd.

Section No.4 (600 lin. ft.) 2% in. do. do. do.

Section No.5 (500 lin. ft.) in. asphalt carpet on 2 in. thick

4, unreinforced concrete trey, thus: + 34 Carpet

The general appearance of the all-concrete length is much the same as when the job was finished. There is no evidence of wear nor are there any defective sections.

In the length where the concrete has been covered with an asphalt carpet, the asphalt is showing signs of perishing, the aggregate being very much ‘exposed” and in some places frittering away. Moss is growing on the surface, especially for a width of 6 to 9 inches along each edge where there is no traffio.

REPORT ON CONDITION OF EXPERIMENTAL LENGTH OF CONCRETE CYCLE TRACK LAID IN 1938 BY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND EAST LOTHIAN COUNTY COUNCIL ON THE EDINBURGH-NORTH BERWICK ROAD, WEST OF LONGNIDDRY, EAST LOTHIAN.

DATE OF INSPECTION 28th MARCH,

CONFIDENTIAL CC, 111.

July, 1946, DEPARTMENT OF SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH

Road Research Laboratory

CO-OPERATIVE RESEARCH WITH THE CEMENT AND CONCRETE ASSOCIATION

- MoT archives, National Archives.

[14] MoT archives say the experimental section was 3,060ft but the concrete cycle tracks measure 4,962ft — the difference could be that only part of the track was used for the experimental surfaces.

[15] Long Eaton Advertiser, 24 June 1938.

[16] Coventry Herald, 11 November 1939

COVENTRY BY-PASS DREAM COMES TRUE

RECENTLY opened to traffic over its full length, the Coventry By-pass, extending the seven miles from Birmingham Road, Allesley, to the London Road, Willenhall, is one of the greatest engineering feats carried out by the city.

Here are the impressions of a ” Coventry Herald ” representative, who traversed the entire length of the by-pass

After leaving Allesley it runs approximately parallel with Allesley Old Road as far as Broad Lane, which it crosses, and then Tile Hill Lane. Next it bridges the railway to Birmingham, passes Canley Lane, and Kenilworth Road, and bridges t: Sowe and Sherbourne rivers before emerging on the busy London Road. At its widest the by-pass covers 150 feet. There are on either side eight foot wide pedestrian paths, cycle paths of similar width, carriageways 24 feet wide, and grass verges between them of five feet.

“As I traversed this road, the finest in Coventry, I met little traffic.

Starting from Allesley, I could see the wide highway spreading before me like, in its expanse, one of the modern German motorways. But it had this difference. It climbs a bit, drops a bit, and curves now and again. Those in Germany are level, monotonously so, and have few curves. ” There are, generally speaking, few trees down the new by-pass, so that the highway seems artificial. On each side there are wooden railings, where hedges would look more natural, and rolling away beyond are fields, and the distant reds and whites of Coventry homesteads.

Some of the fields are empty and waiting for the builder. Some have signs of still being under the agricultural whip, others have dumps of building materials, and in others stand cows—like mourners gazing at the funeral of Mother Earth.

Houses were being erected on my left, and a service road already existed in front of them.

Land fronting the road, which was worth £4OO an acre before the work was undertaken, has been estimated as being worth £1.600 an acre afterwards! Where building is going on this estimate has probably been proved. ” Are they the forerunners of a great new housing estate, these rapidly springing-up villas! Where traffic rumbles there usually follow shops and houses. Perhaps this side of Coventry will change its face completely owing to the new road! ” There are, surprisingly, not many good views from the by-pass.

I inspected all the tracks, The cycle paths, particularly, because cyclists are opposed to them. They are wide enough for three to cycle abreast, and for two to pass comfortably. The surface is good, and the dips into the highway at junctions, are smoothly finished off.

If people will walk on their own paths—not like the people near the Burnt Post, who were taking a pram along the cycle track—the cycle paths should be useful. I hope that people waiting for a ‘bus. or dismounting, will not leap into the cycle path! I imagined myself a pedestrian trying to cross this wide road. I should leave the house on one side and look carefully before crossing the service road. Then I would cross a verge and look timidly before nipping over the cycle track to the next verge. Then another look for danger before flitting over the main road to the centre island! Then all over again to the other side! Phew!

[17] Wright Miller, Esq., 1, Galen Road, Putney, S.W.15.

Letter to MoT, 24th March 1927, MoT archives.

[18] . They were too narrow — Eric Charles Claxton, The Hidden Stevenage: The Creation of the Substructure of Britain’s First New Town, Remembered, Book Guild, 1992.

[19] This was stressed by a Ministry – Interim Report of the Committee on Road Safety, Ministry of War Transport, H.M.S.O., 1944.

[20] Birmingham Daily Gazette, 9 June 1954.

[21] Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, Committee on Road Safety, Report on child cyclists, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1956. https://archive.org/details/op1265790-1001

[22] Hilary Watts, letter to The Times, public relations officer, British Cycle and Motor Cycle Manufacturers and Traders Union, Allington House, 136, Victoria Strett, London SW1. The Times, Dec 21, 1954.

[23] Segregating The Road Users, The Times, March 13, 1961.

[24] Planning for bicycles, letter to The Times, J. J. LEEMING. The Times, May 11, 1977.

Leeming started working with Oxfordshire County Council in 1924, riding to become Deputy County Surveyor until he left for Dorset in 1946 to become County Surveyor, where he stayed until his retirement in 1964.

Writing in 1969, Leeming described what is now known as “induced demand.”

“Motorways and bypasses generate traffic, that is, produce extra traffic, partly by inducing people to travel who would not otherwise have done so by making the new route more convenient than the old, partly by people who go out of their direct route to enjoy the greater convenience of the new road, and partly by people who use the towns bypassed because they are more convenient for shopping and visits when through traffic has been removed.”

Road Accidents: Prevent or Punish? Leeming, J. J. Cassell, 1969.

[25] Daily Herald, 10 September 1935.

[26] CYCLE TRACKS.

HC Deb 22 May 1935 vol 302 cc334-5 334

Mr. HALES asked the Minister of Transport whether the use of the new cycle tracks on arterial roads is optional or compulsory by cyclists; and, if compulsory, are cyclists using the main roads subject to prosecution for an infraction bf the Highways Act?

The MINISTER of TRANSPORT (Mr. Hore-Belisha) Optional.

Mr. HALES asked the Minister of Transport whether he is aware that the objection of cyclists to the new cycle tracks is owing to the said tracks being frequented by pedestrians; and whether he will take steps to secure that these tracks shall be for the exclusive use of cyclists?

Mr. HORE-BELISHA A census which I recently had taken showed that over 84 per cent. of all cyclists proceeding along the section of Western Avenue, where cycle tracks have been provided, used the tracks. Signs have been erected at intervals stating that the tracks are for cyclists only.

Mr. HALES In the absence of separate tracks for pedestrians, how is the hon. Gentleman going to deal with the problem of the pedestrians and the cyclists using the same track?

Viscountess ASTOR Will there be any penalty on cyclists who fail to make use of these tracks, considering that a high percentage of those killed on the roads are cyclists?

Mr. HORE-BELISHA I have said that 84 per cent. do, in fact, use the tracks.

[27] CYCLE TRACKS.

HC Deb 03 July 1935 vol 303 cc1853-4 1853

§31. Mr. WEST asked the Minister of Transport whether he has decided to make cycle-tracks compulsory on all newly-constructed arterial roads?

§Mr. HORE-BELISHA No, Sir. Where it appears that the proportion of cyclists to other traffic is likely to be appreciable, I shall use my best endeavours to secure that separate tracks are provided as circumstances permit for the use of cyclists.

§Mr. WEST Has the hon. Gentleman considered, as an alternative to cycle tracks, constructing special motor tracks?

§Mr. HORE-BELISHA One arises to some extent out of the other. If cyclists are segregated, motorists are more segregated than at present.

§Mr. PALING If cycle tracks are provided, is the use of the main road prohibited to cyclists?

§Mr. HORE-BELISHA No, not yet.

§Sir W. BRASS Where cycle tracks are provided, are they being used by cyclists?

1854

§Mr. HORE-BELISHA

[28] Daily Herald, 26 May 1936.

[29] Western Morning News, 2 July 1936.

[30] Transport minister Captain Hudson: “We are proposing to improve the lay-out of the Great West Road, including the provision of cycle tracks nine feet instead of six feet wide.”

GREAT WEST ROAD (CYCLE PATHS).

HC Deb 14 March 1938 vol 333 c29 29

[31] “Cycle Census – Great West Road”, September 18, 1937, Ministry of Transport. See: CYCLE TRACKS: Proposed construction, 1926-1943, Ministry of Transport, MT 39/127, National Archives.

By the 1960s, usage had flipped on this road:

“Between 5.30pm and 6pm there were 144 cyclists using the west bound cycle track on the Great West Road in London, and just one using the main carriageway.”

From Pedal cycle census taken on 17th May 1962 outside Pyrene factory, Great West Road, [London], 200 yards west of Firestone Bridge, Ministry of Transport archives.

[32] Barton-Whitwell Diversion A.64. Cycle Tracks. and 118 tracks The figures instant, between the hours of 8.0 a.m. and 10.0 p.m. on the above road was taken

A census of cycles “using” and “not using” the cycle tracks on Sunday 20th June show that 821 cyclists were using the tracks and 118 the dual carriageways.

R. SAWTELL.

County Surveyor. the Divisional Road Engineer, Ministry of Transport, Britannia House, Wellington Street, Leeds, 1. NORTH RIDING OF YORKSHIRE.

County Surveyor’s Office,

County Hall, NORTHALLERTON.

24th June, 1937

[33] Letter 28th June 1937.

[34] This crossing point is still there: https://goo.gl/maps/sJhntwrESjuDHKS27

[35] Yorkshire Evening Post, 7 June 1937.

[36] Leeds Mercury, 9 June 1939.

[37] Nottingham Evening Post, 10 April 1939.

[38] Letter from MR MAURICE G EVANS, Tarrystone, Philip Road, High Wycombe, The Times, 17th April, 1935.

[39] Mr. JOHN A. BEARDER, 151, Huddersfield Road, Halifax. Points from Letters.

The Times , September 30th, 1935