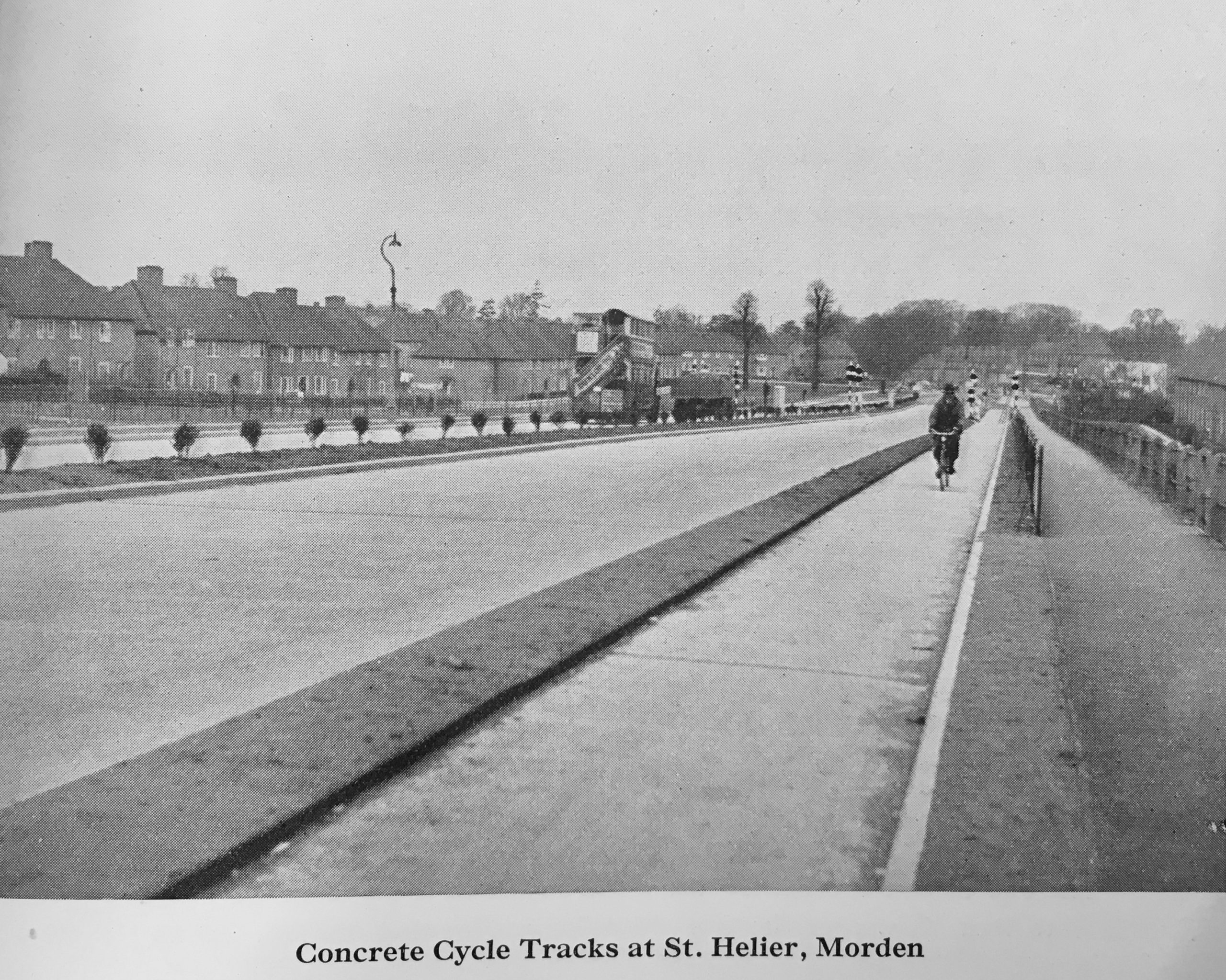

St. Helier Avenue, c. 1936.

“The magic-ray traffic light at Morden was a great success last night with hundreds of schoolchildren,” the Daily Herald reported in April 1936.

“It became visible after dark, and the boys and girls invented a new game which kept the traffic lights continually changing,” stated the paper, adding that the “crossing is at St. Helier Avenue … where there are dual carriage ways, cycle tracks and footpaths, and a 100-yard wire fence divides the footpaths from the road.”

The experimental crossing — on what the press called the Ministry of Transport’s “model road” — was inaugurated by the Minister of Transport.

Southern end of St. Helier Avenue.

“When Mr. Hore-Belisha put the new signals into operation he passed through a gap in the fence and interrupted an invisible ray a little less than three feet above the ground,” added the Daily Herald.

“‘Cross now’ invited a signal between the cycle track and the carriageway,” continued the paper.

“In the middle of the road another light ray was broken, and similar signals gave the Minister safe conduct across the second carriageway.”

This anecdote is one of many which confirms the cycle tracks on St. Helier Avenue were in use from March 1936.

Then and now at the same spot on St. Helier Avenue.

A report in a trade magazine suggests the tracks had been completed the previous month.

“As result of a visit we recently paid to inspect the construction of cycle paths on St. Helier’s Avenue, Morden, we are able to give exclusive details of the design and working of the first all-British machine for the levelling and tamping of concrete road surfacing,” revealed Roads and Road Construction in February 1936.

“The present job being undertaken by this machine is the construction of concrete cycle paths at St. Helier’s Avenue, Morden. Altogether a strip of road, [four and a half] miles in length, is being laid out with these paths.”

As St. Helier’s Avenue is a smidge under a mile long, that additional mileage probably refers to the cycle tracks on the linked Sutton bypass.

The St. Helier estate was built between 1929 and 1934 by the London County Council as an overspill municipal housing estate for people displaced from run-down areas of Inner London. The estate was named for Lady St Helier, an LCC alderman and councillor between 1910-27 and designed as a garden city, with landscaping by architect Edward Prentice Mawson.

By the end of the 1930s there were 9,068 houses and flats on the estate, housing almost 40,000 people who were well served with bus and train links, as well as the cycle tracks. In an aerial photograph from 1949 the cycle tracks on St. Helier Avenue can be clearly seen; clearly seen because there are no cars parked on them.

In another period photograph, above, this time probably from 1936 or so, a man in a white jacket is shown cycling on the cycle track. A chainlink wire fence separates the concrete cycle track from the asphalt-surfaced footway.

Writing in the Daily Herald in 1938, the anti-cycle-track cycling writer Kuklos complained that “use of cycle paths … may be made compulsory on condition that they are adequate and are reserved for cyclists only. This would require those wire fences which the angry householders of Morden broke down on St Helier Avenue.”

The cycle track in this period photo is at Leominster Walk: https://goo.gl/maps/aEB7sMHxzP9soPKd6

The chainlink fence has long since been replaced with a bush. Motorists are allowed to park their cars on what was once the cycle track, an arrangement that’s at least 45 years old, reveals the 1977 photograph above. Today, as in 1977, the adjacent footway is a shared-use path. It’s possible St. Helier Avenue’s cycle tracks were grubbed up soon after they were installed — a news snippet in The Bicycle from November 1936 stated that a meeting of Merton Council heard that the MoT “had agreed to the removal of the cycle tracks” following “agitation by residents” who had “complained that the cycle tracks were a nuisance, were badly placed …” The weekly magazine added: “The carriage-ways are now to be widened.”

Cars block the 1930s-era cycle tracks of St. Helier Avenue, 1977.