Britain’s mid- to late-1930s cycle tracks were modelled on Dutch cycle-specific infrastructure built in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but across the world, there had been earlier phases of provision for cyclists.

The first purpose-built cycleway was constructed in 1892 on Copenhagen’s Esplanaden, a waterfront, tree-lined promenade. An earlier Dutch cycleway — used from 1885 and still in use today — had been converted to a cycleway.

The Netherlands was not a “cycling nation” at the time. Instead, the world’s best 19th-century cycleways were all American. One was even grade-separated. Such vertical separation was common for rail infrastructure — New York’s Central Park also had underpasses for pedestrians when it was laid out in the 1860s — but the elevated California Cycleway made news worldwide when it was erected in the late 1890s.

After forming the “Good Roads” movement in the 1880s, pushing for better roads for all users, especially those on cycles, some American cyclists also started to advocate for “wheelways” adjacent to roads. These “sidepaths” were wildly successful for a short period, with thousands of miles of them across the country, making America by far the most bicycle-friendly country in the world for a short number of years. Side paths were “spreading with unexampled rapidity,” wrote one observer in 1900, and they would soon form a “network of passageways for bicycle riders the continent over.”

By and large, these sidepaths were not created to protect cyclists from other road users but to provide uppity cyclists with smoother surfaces. Separating cyclists from other road traffic has often been divisive.

Starting with Denmark, here’s a country-by-country description of the early provision for cyclists.

DENMARK

“Wherever space is available [in Copenhagen, Denmark], well-paved cycle tracks (about 8 ft. wide) are provided,” Sir Charles Bressey, the outgoing chief engineer at the UK’s Ministry of Transport, wrote to his successor Major F.C. Cook in 1935.

“Pedal cyclists constitute the greater bulk of the road users,” continued Bressey.

“On some narrow roads in the heart of the town, I tried to take a count at a quiet time on a week-day afternoon; cycles were then passing at the rate of 40-45 a minute. At peak times, I do not think I could have counted them.”

This abundance of cycle traffic — which impeded motorists, complained Bressey — was not new. Copenhagen had been a cycling city since the 1890s.

The city’s first cycle track, on Esplanaden, was constructed in 1892. Few others joined it until the 1920s.

“Denmark’s Cyclists Demand Bike Lanes Along Roads!” stated the Danish Cyclists’ Federation (DCF) in a series of adverts placed in 98 newspapers in 1922.

And these bike lanes should be separated with kerbs or bollards, argued DCF.

“If there isn’t a boundary between the car lanes and the bicycle lane, then the bicycle lane isn’t worth much,” said DCF vice chairman Max Tvermoes in 1922.

In Copenhagen in 1923, a separated cycle track was built along Roskildevej to Glostrup. It’s still there. In the same year, use of cycle tracks was made mandatory throughout Denmark.

In 1926, Denmark’s Technical Road Committee (Den Tekniske Vejkomite) published the Dansk Vejtidsskrift traffic guide, which advised placing cycle tracks on filled-in ditches alongside roads or placing them on the far side of the ditches, creating a buffer between cyclists and cars.

The construction of bicycle infrastructure was discussed at the AGM of the Association of County Councils in July 1929. Separating traffic was a compelling necessity, even though it cost money and demanded space, stated vice-chairman Henningsen of the National Tax Council (Landsoverskatterådet) in his AGM speech. Cycle tracks should be of high quality, he argued; otherwise, cyclists would use the road.

County Inspector Troelsen from Aalborg, in a speech about “bicycle stripes,” said that on the country roads of Northern Jutland, cyclists didn’t mind cycling on the narrow painted lanes on the shoulder of the roads. Therefore, the county road administration had widened the asphalt on the sides of the road to allow for one metre on either side for cyclists.

The town of Aalborg had built physically-separated cycle tracks along the roads leading to the town centre but they were little used, the council complained.

In 1930, there were only about 88 km of bicycle infrastructure along roads in Denmark. By 1933, this had increased to 342 km, but that was only four percent of the country’s roads.

1.5 million people — 44 percent of the population — rode bicycles daily in the early 1930s.

Cycle track compulsion, where such tracks existed, was introduced by the Traffic Law (Faerdselsloven) of 1932.

In the mid-1930s, the construction of cycle tracks alongside new major urban highways was made compulsory. The Law on the Establishment of Cyclepaths and Footpaths of November 1938 allowed local authorities to “Build cycle paths and footpaths along roads, where from a traffic point of view they were deemed necessary.”

High-quality cycle tracks were advocated by Danish Road Laboratory’s Road Committee (Dansk Vejlaboratoriums Vejkomite) in Views on the Implementation of Bicycle Lanes, Bicycle Stripes and Pedestrian Paths of 1938.

“Since there are two million cyclists for one hundred and thirty thousand cars, the question of cycle paths is of the utmost importance in Denmark,” said a French cycle touring magazine in 1938. “The Danish judge that the tracks must always be established on both sides of the roadway and that their surface must be perfectly rolling.”

NETHERLANDS

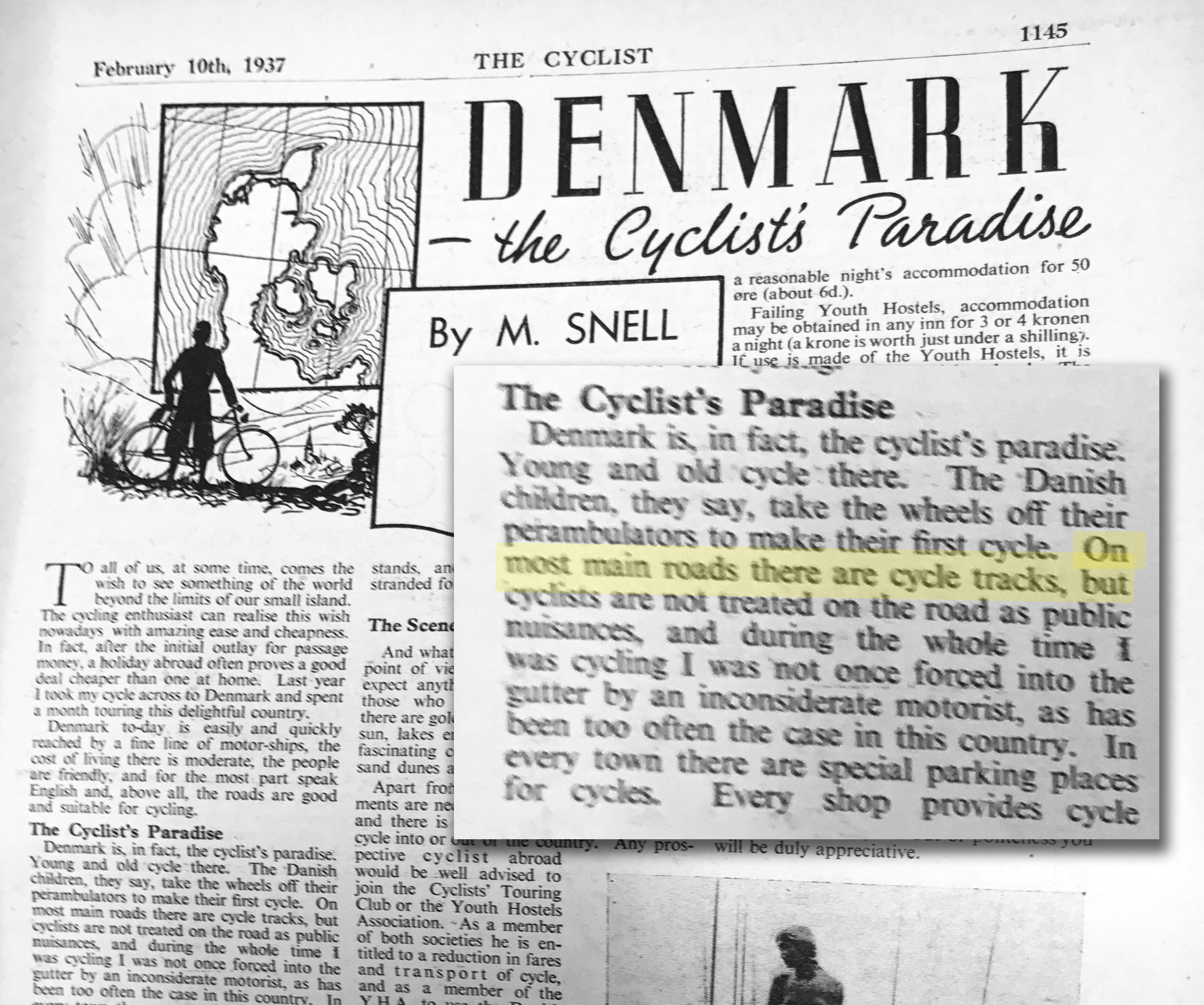

“We Hollanders,” editorialised De Kampioen, the Dutch cycling and motoring magazine, in 1935, “have the finest cycle paths in the world …” This “thick net of cycle paths … is now spread over the whole of the country.”

The Netherlands had been expanding its cycleway network since the 1890s and had become the world’s leading bicycling nation by 1906.

There are compelling cultural, historical, and socio-economic reasons why the Netherlands is a cycling nation. It is not just because the Netherlands is pancake flat (as are many places), or that parking a car is difficult (the same can be said of many cities outside of the Netherlands), or that Dutch streets are wide (many world cities also have wide streets, but no cycling). It’s a mix of all these reasons and more, including, of course, the fact that the Netherlands now has a wonderfully dense network of cycleways, quiet streets and “bicycle streets” where motorists are “guests.”

Much of the Netherlands was constructed by hand, and infrastructure building and maintenance are well funded and prioritised. The Dutch equivalent of “sink-or-swim” is “pump-or-drown” — pompen-of-verzuipen — and inundation is a constant fear for a low-lying country, much of which was reclaimed from the North Sea. Dutch people have a saying: “God created the world, but the Dutch created the Netherlands.” There’s a shorter word for it: maakbaarheid, the need to control one’s surroundings. Saltwater has been turned into grass-and-soil polders since at least the ninth century (“nether land” means “low land,” and polders are areas of reclaimed land protected by dykes). Such reclamations require ingenuity, hard work, and constant vigilance. They also demand communal effort — the rich man’s fields get flooded at the same time as the poor man’s fields, and if they don’t work together to pump the water out, they would both drown. In medieval times, even when different cities in the same area were at war, they still had to cooperate to pump away seeping water. This is believed to have taught the Dutch to set aside differences for a greater purpose. There’s also a deeply held sense that infrastructure is important, that access to this infrastructure should be equitable, and that maintenance of this infrastructure is something for the whole community to sweat over. Dutch people are famously brusque — often to the point of rudeness — but this no-nonsense, straight-to-the-point attitude is thought to have been shaped by finding practical, no-fuss solutions that benefit the common good. Infrastructure is both valuable and valued. It is also constantly renewed.

Britain’s Department for Transport/Ministry of Transport started life in 1919 as the Department of Ways and Communications; America’s Department of Transportation was born in 1967. The Dutch equivalent is the Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment — or Rijkswaterstaat — and it was founded in 1798. The Chinese famously take the long view of history, and Dutch nation-builders take the long view of infrastructure.

Because of the folk knowledge that constant vigilance is needed against flooding, the average Dutch person’s attachment to order can reach extreme proportions. When, in the past, poor maintenance of a dyke would result in catastrophic flooding, citizens had every incentive to keep things tidy and well-ordered. An English author observed in 1851: “One of the principal characteristics of a Dutch street is its scrupulous, or it would be more correct to say, elaborate, cleanliness.” This obsessive cleanliness is a cliché, perhaps, but it’s a national trait to want to keep life under strict control. Planning is almost a religion, and everything has to be in the right place. Mixing fast cars and slow bicycles militates against this natural order of things.

“The short distances between housing and facilities (such as offices, shops, schools, nightlife locations, stations, sports centres, etc.) in Amsterdam add to the attraction of cycling as a form of transport,” says Amsterdam’s tourist board. “Cycling is a fundamental part of Dutch culture,” it adds.

Part of the Dutch psyche is said, by some, to be derived from religion. Roughly speaking, the northern half of the Netherlands (where most people live) is Calvinist, a strict and famously thrifty form of 500-year-old Protestantism, and the southern half is Roman Catholic. (Belief in God is not the point here; it’s the cultural baggage that counts.) Cycling goes one theory, appeals to Calvinists because it’s simple, sober, and, above all, cheap. And as Calvinists — and many Dutch people — do not like ostentation or the flaunting of wealth, cycling is the perfect fit, especially on heavy, black, and anonymous Dutch bikes. Riding such a bicycle is egalitarian, not status-enhancing.

Even though plenty of Dutch people do self-identify with these supposed “national characteristics,” and Calvinists do cycle more than Catholics, such explanations have to be taken with a pinch of salt. An eminent Dutch historian believes the “prudent nation” trope to be more of a foundation myth than factual. And according to the author of Why the Dutch Are Different, the Netherlands has never actually been a country “where office workers smoked weed over their desks, visited prostitutes at lunchtime, and euthanised their grandparents in the evening.”

What’s not in doubt is that the Netherlands has been building separated cycleways for longer than any other nation. Even the “unravelling” of modes is not modern. As early as 1595, one-way traffic for carts had been mandated in some of Amsterdam’s alleys, and in 1880 Harper’s New Monthly described a “little town in Holland in the streets of which no horse is ever allowed to come. Its cleanliness may be imagined, and its quiet repose.” The first cycleway in the Netherlands was converted from a sidewalk in 1885 on the Maliebaan, a long, straight road in Utrecht. This gravel cycle path was created for high-wheel riders by 44 members of the Algemene Nederlandse Wielrijders Bond (Royal Dutch Touring Club), ANWB for short, and founded two years previously. Originally a members-only racing track, it was opened for all cyclists in 1887 and was later extended to become a regular cycle path; it’s still used today.

One of the first purpose-built cycleways in the Netherlands was in Eindhoven, constructed in 1896. Factory owners Jacob Tirion and Robert Carlier wanted a cycleway for their workers. Their textile factory was in the hamlet of Eeneind, between Tongelre (now part of Eindhoven) and Nuenen. They originally chose Eeneind because of the railway station — Nuenen-Tongelre — on the track between Eindhoven and Venlo. On June 3rd, 1896, Carlier wrote a letter to the local municipal board of Nuenen asking for permission to create a bicycle path next to the road that runs from the railway station to the centre of Nuenen. The board agreed and the track was created. It was built as a smooth path using coal-ash and clay but was also used by horse carriages, quickly rutting it. In November of the same year, Carlier wrote again to the local municipal board, this time asking for permission to place wooden poles between the road and the bicycle path. This would separate the cyclists from other wheeled traffic. Permission was granted — Carlier paid for the poles. The cycleway was 3 kilometres long and ran from the railway station to the centre of Nuenen, close to where the statue of Vincent van Gogh stands. (The painter often took the train from the Nuenen-Tongelre railway station.) The railway station was demolished in 1972 and from the original bicycle path only the 200 metre piece on the Stationsweg in front of the railway station remains.

The separation of transport modes — alien everywhere else — quickly became standard in the Netherlands. In 1898, The Spectator reported: “On the route from the Hague to Scheveningen there lie parallel to each other a carriage road, a canal, a bicycle track, a light railway, sidepaths regularly constructed…”

The same year, the ANWB created a Wegencommissie, or National Roads Commission, which pressured state authorities to build and improve roads. Later, this cycling club hired its own road engineer to advise local cycling clubs on the technical and legal matters regarding the construction, design, and maintenance of bicycle paths. A. E. Redelé also supplied the clubs with building materials for creating these paths.

Sociologist Peter Cox has said the cycling infrastructure provided for cyclists at this time “played in important role in overcoming the unsuitability of the existing roads because as a policy it was a part of a clear intention to use the cycle roads system to raise the status of cycle users as citizens, indeed to prioritise them.” Those on bicycles at this time were the elites, including those with double names indicating Dutch nobility, and there were not all that many of them. While America and Britain were experiencing the “cycling mania” of 1896—1897, sales of bicycles in the Netherlands were comparatively low — just 94,370 bicycles were being ridden in 1899, a ratio of one bicycle per 53 inhabitants. Six years later, the bicycle total had risen to 324,000, the highest ownership in the world, and by 1911, the number of bicycles owned in the Netherlands had doubled to 600,000, an ownership ratio of one in ten.

Cycle historian Kaspar Hanenbergh has said: “ANWB used their power to lobby for separate roads. Very reluctantly, local government took up this role, but in the early years private initiative was far more effective. The ANWB supported local Rijwielpadverenigingen, or bicycle path societies.”

The first was formed in March 1914 in the Gooi and Eemland region, and others followed, including Drenthe in 1916 and Eindhoven in 1917. These cycle paths were rural, recreational, and largely middle-class. Following the end of the First World War, an economic slump in defeated Germany led to a flood of cheap German-made bikes into the Netherlands, encouraging wider social use of the bicycle, which had already become a national icon. (It also helped that tram-ride prices tripled in the same period.) The excellence of Dutch bike paths was featured in a 1920 report in the German bicycle trade magazine Radmarkt:

We have to thank the efforts of the [ANWB] for the extensive network of good bicycle roads that exist along the main highways of the country. There are equally good bicycle roads leaving the highway into all remote places… In each street there is at least one, but generally at each side, a specially designed “clinker” pavement… [In] Holland accidents fell to a minimum through the exemplary construction of these paths.

In 1921, the Times of London noted “the enormous number of bicycles” in the Netherlands and how it had “ideal road conditions” and an extensive bicycle path network that “testifies to the important place which cycling occupies in the life of the people of the Netherlands.”

“We Hollanders have the finest cycle paths in the world … [This] “thick net of cycle paths … is now spread over the whole of the country.”

De Kampioen, the Dutch cycling and motoring magazine, 1935

According to a Dutch newspaper in 1922, pedestrians found intersections in Amsterdam dangerous not because of cars but because of the sheer number of people on bikes. “That endless, unbroken row of three, four cyclists riding beside each other along the whole length of Weteringschans makes crossing the street deadly!”

On main roads, cyclists accounted for 74 percent of the traffic, compared to just 11 percent for automobiles.

In the summer of 1924, cyclists were slapped with a “bicycle tax.” Initially, it paid for flood defences and schools, but it was soon channeled to cycle-path construction and thereafter also paid for roads for motorists. According to academic Anne-Katrin Ebert, “The bicycle tax put cyclists on the political map and helped create a tradition of traffic engineering devoted to cycling paths and regulation. This would form an important basis for the ‘survival’ of the Netherlands as a cycling nation.”

“Everyone in Holland cycles,” opined a US newspaper in 1924, “and everyone can cycle everywhere” because “there is a wonderful system of roads and pathways for the cyclist…”

In 1926, cyclists were paying more into the Wegenfonds, or Road Fund, than motorists. The following year, the government announced the Rijkswegenplan, a national road-building plan mostly for motorists but paid for mostly by cyclists, although when many of the town-to-countryside arterial roads were constructed in the 1930s, they were provided with separated cycleways, too. Urban cycleways were built on a few major Amsterdam streets in the same period, although cyclists complained that they were often blocked by pushcarts.

The ANWB fought for the removal of the bicycle tax, or at least reduced rates for working-class cyclists. Still, it’s inescapable that by paying this tax, cyclists became important actors on the national scene, and this influence continued even after the tax was later abolished.

Then, as now, Dutch cyclists (especially those in Amsterdam) did not have a very good reputation with other road users. In 1928, an American journalist wrote “traffic in Holland … is as completely dominated by [the bicycle] as in America it is dominated by the automobile, [but the] Dutch cyclist is even more indifferent to the rights of others than is the American taxi driver.”

Because of their sheer numbers, Dutch cyclists ruled on the roads and didn’t pull to one side for motorists, as was expected to happen in Germany. A German visitor to the Netherlands was amazed at how Dutch cyclists had defended “with great doggedness” their right to the roadway. “In Germany, this right has long since been lost,” he noted. “In Holland, this right has remained as a consequence of a true democracy.”

In 1933, Karel Čapek (the Czech writer who introduced the word robot to the world) was impressed not only by the numbers of Dutch cyclists but also how they moved:

I have seen various things in my time, but never have I seen so many bicycles as, for instance, in Amsterdam; they are no mere bicycles, but a sort of collective entity; shoals, droves, colonies of bicycles, which rather suggest teeming of bacteria or the swarming of infusoria or the eddying of flies. The best part of it is when a policeman holds up the stream of bicycles to let pedestrians get across the street, and then magnanimously leaves the road open once more; a regular swarm of cyclists dashes forward, headed by a number of speed champions, and away they pedal, with the queer unanimity of dancing gnats.

An American travel journalist writing in 1934 wondered: “if there really is anything in all this talk about evolution another century will see the Dutch children coming into this world on tiny bicycles.” He added that in the Netherlands the bicycle had become “almost a part of the body.”

A year later, a Dutch newspaper proudly described the nation’s “dense network of cycle paths”:

No other country has started earlier with such an elaborate and systematic construction of special roadways for cycle traffic. What we have achieved … commands admiration from compatriot and foreigner alike. …. With regard to cycling traffic, our country has taken a position like no other. The traffic counts for 1932 have shown that of all traffic on national highways fifty percent is that of cyclists. In such a situation it can be considered important, not only for cyclists, but also for other road users, that cyclists have their own roadways, the cycle paths, as much as possible.

In 1935, the Netherlands had 3,308,000 bicycles for a population of 8,390,000, or 40 cycles per 100 people. At the same time, there were only 89,575 motor cars in the country. In the same year there were 1,396 km of main road cycleways, covering approximately two-thirds of the Dutch road network. There were also 2,400 kms of off-carriageway cycleways.

A giant two-level roundabout was constructed during WWII in Utrecht from 1941 to 1944 — it kept cyclists and motorists apart. The Berekuil — or “Bear Pit” — had been designed in 1936, and is still in use today, although it has been modified over the years.

According to a report in an English newspaper in 1939, Dutch cyclists “had roundabouts of their own at crossroads, and these tracks were sunk below the road level.”

GERMANY

Bremen, Hamburg, Luneburg, Hanover and Magdeburg all had extensive, leisure-oriented cycle path networks by the early 1900s, created by such organisations as the Magdeburg Association for Bicycle Ways, Magdeburger Verein für Radfahrwege, a middle-class cycling organisation founded in 1898. These paths were modelled on those in the Netherlands and led from the city to recreational areas

By 1926, the city had established a 285-km network of tracks, jointly paid for by the municipal council and the Magdeburg Association for Bicycle Ways; the tracks were reserved exclusively for club members. The prime mover behind the 1920s cycle tracks in Magdeburg was traffic planner Dr. Carl Henneking.

While the first cycle tracks in Germany had been wide, well-designed and constructed for the (paying) convenience of cyclists, those that followed in the late 1920s were inferior. The cycle paths called for in 1926 by the Research Association for the Construction of Automobile Roads, STUFA, were good on paper (Henneking was a STUFA member and drafted the group’s cycle track guidelines) but when built by Central Office for Bicycle Ways, Zentralstelle für Radwege, they were narrow, made from cheap materials and indirect. Magdeburg’s model of cycle tracks paid for by subscription — in effect, a voluntary fee — did not work in other cities where the majority of cyclists were working class and could ill afford such fees.

In 1933, Fritz Todt, the Inspector General of German Roads, aimed to reduce bicycle traffic on the streets to favour motorists; cycle tracks were to be used as a deliberately demeaning way of separating cyclists from motorists. The Reich Association for Bicycle Path Construction, created in 1933, absorbed the tasks of the Central Office for Bicycle Ways, supervised by Todt.

The new and inferior cycle tracks were referred to as “the roads of the little man.” A period French cycling magazine estimated that there were 17 million cyclists in Germany in 1936.

Under the Nazi regime, the 1934 Reichs-Strassen-Verkehrs-Ordnung regulated the separation of traffic and the Radwegebenutzungspflicht forced cyclists to use cycle tracks. Use of such tracks, when provided, was mandatory even if the cycle track was poorly designed, surfaced or maintained. There was no outcry from cycling associations because they had been either outlawed or brought within the fascist fold as the Nazi-controlled Deutscher Radfahrer Verband (German Bicycle Association). In the run-up to the Berlin Olympics of 1936, Nazi propaganda crowed: “Let us show the marvelling foreigners proof of an up-and-coming Germany … where the motorist has bicycle-free access not only to the autobahns but to all roads.”

The technical director of the Reich Association for Bicycle Path Construction was the road engineer Hans-Joachim Schacht, who was still involved in German bicycle planning until the 1950s. In 1935, the charity organised a Berlin exhibition, ‘Germany needs bicycle paths.’ The exhibition calculated that the country had 5,000 km of existing cycling paths available and would soon need 40,000 km. Between 1934 and 1939, 6,000 km of new cycle tracks were constructed, mainly funded by municipalities.

In August 1935, Schacht invited the MoT’s chief engineer, Major Cook, to visit the cycle tracks exhibition in Berlin, which would be staged until 7th September of that year. Cook replied that he couldn’t attend but said he would be “grateful for any literature … bearing on the question of cycle tracks.”

Literature was duly sent by Schacht, which Cook said included some “interesting documents” and that the MoT would hope to “take every possible advantage of.”

According to a 1937 article by Schact in a British road construction magazine, Germany had a highway length of 291,000 km, [with] approximately 5,200 km of cycle tracks and 2,100 km of cycle paths.

“In Breslau,” he wrote, “the device the cycle track has been hit upon of subdividing into two paths, a track proper of 1.42 metres wide and safety path of 0.42 metres wide, the latter as a rule not being ridden on but serving only for passing.”

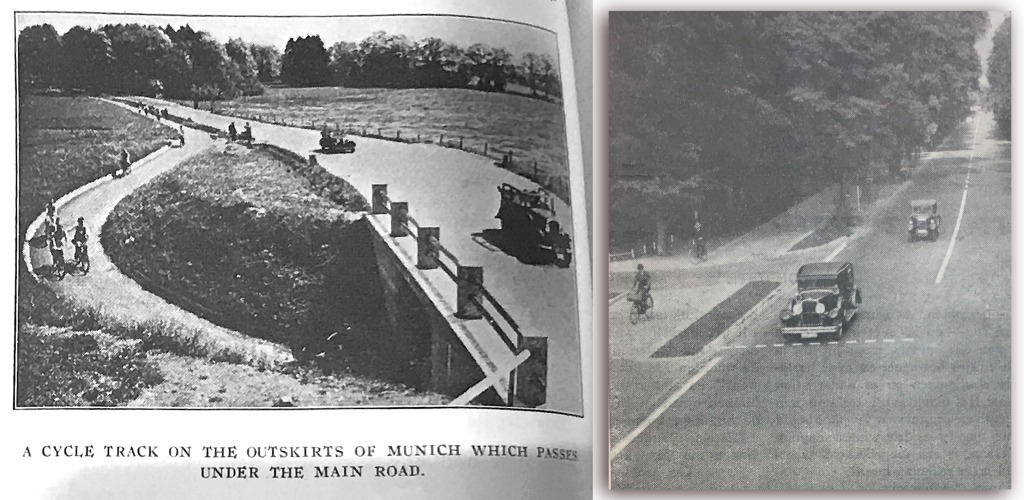

“As a further means to eliminate risks, may be mentioned the precaution taken of leaving the cycle track on the turnpike from Munich to Starnberg below the road. This example has already been copied at five other similar positions in Germany, subterranean cycle tracks have also been built.”

AMERICA

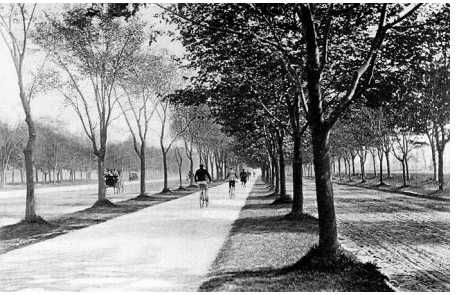

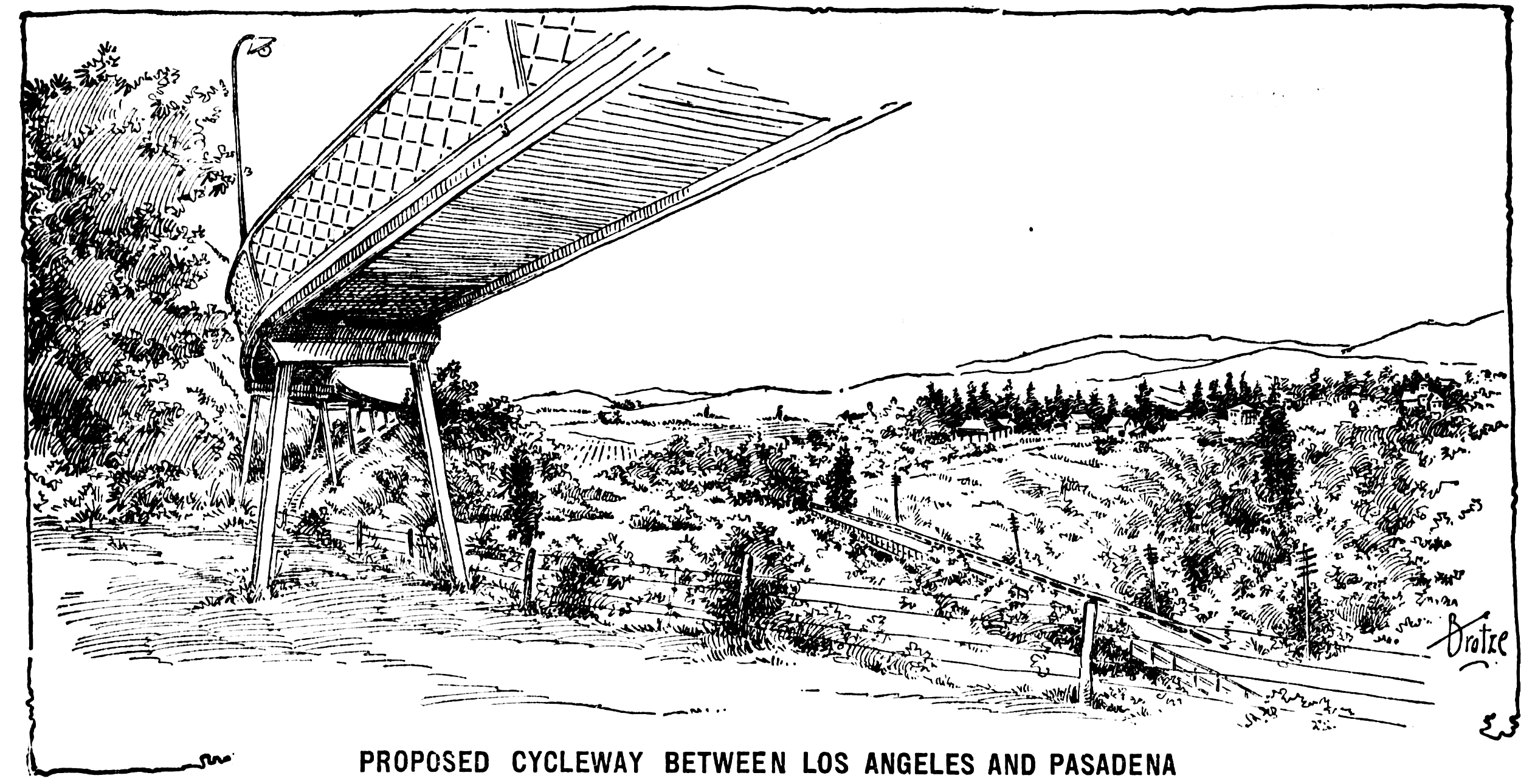

In 1890s New York, there was a wildly popular bicycle-specific “pleasure route” from downtown Brooklyn to the happening resort of Coney Island. On the West Coast, there was an ambitious cycle path on timber trestles, a road-in-the-sky for cycle commuters between Los Angeles and Pasadena.

Elsewhere in America, Good Roads activists — frustrated by the continued poor quality of the nation’s rural roads — took matters into their own hands and built “wheelways” for use by cyclists. These cycle paths — also known as “sidepaths” — were long-distance demonstrations of how Good Roads could be built.

“The paths are being built from city to city and from town to town … and [are] proving invaluable object lessons in the good roads movement,” claimed a newspaper in 1900:

A farmer travelling along an almost impassable road with a dry, smooth and durable cycle path alongside does not need to be told the advantages of good roads. The object-lesson roads built by the Office of Road Inquiry in the mid-1890s were short. Cycle paths were narrower but just as soundly constructed, and there were thousands of miles of them. Today, this forgotten cycle path network lies hidden beneath modern roads. In some regions, the cycle path network was dense. Outing magazine claimed in 1900 that “over one hundred and twenty-five miles of excellent wheelways, perhaps the best in the world, gridiron the territory about Rochester, N. Y.

Some of America’s first cycle paths were utilitarian, built ruler-straight from city to city, such as the 15.2-mile Albany—Schenectady path in New York State, which became the modern State Route 5. Others were meandering and scenic, such as the 41-mile path around Chautauqua Lake, also in New York State. Plans were to connect many of the city-to-city paths into long-distance routes. In 1900, The New York Times reported on the proposed 968-mile “trunk line” cycle path between New York and Chicago. “Work will begin in the near future …” to connect those cycle paths which had “already been constructed.”

Cyclists paid for these cycle paths themselves, paving the way, as it were, for the later taxes on motorists, which helped pay for the interstate roads that, ironically, poured asphalt over the cycle paths, wiping them from the map and memory.

In the late 1860s, Charles Anderson Dana, the velocipede-riding editor of the New York Sun, advocated the building of “an elevated railway from Harlem to the Battery — from one end of New York to the other — for the use of riders of velocipedes only.” This was “to be thirty feet wide, on an iron framework, and the flooring of hard pine.”

The structure remained a dream, but thirty years later, the call for dedicated cycling infrastructure had become louder and more insistent. An elevated bike path between Harlem and the Battery was again considered, with cyclists dreaming of a “delightful tour” on a midsummer night, “catching glimpses of the Hudson at the cross streets, until the moonlit bay bursts upon the view in all its silvery glory!”

(Of course, the reality would have been far different, with cyclists close to trains and facing the not inconsiderable difficulty of how to get a bicycle onto a trestle without long, shallow and space-hungry ramps.)

There were also proposals for cross-country cycle-path trestles. In 1895, one newspaper reported that “it is proposed to construct an elevated cycle roadway, 16ft wide, of wood paved with asphalt, between Chicago and Milwaukee, a distance of 85 miles …”

During the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896-9, an American entrepreneur proposed building the “greatest bicycle roadway in the world” in order to help those would-be prospectors setting out to reach Canada’s Yukon region on bicycles. Many miners-to-be set off from Seattle on beefed-up “Klondikespecial” bicycles, but they never got the “Klondike bicycle track.”

Today, the concept of a city-to-city grid of bicycle paths would be considered for recreational use only (outside of the Netherlands, that is). In the 1890s, city-to-city bicycle paths were built for day-to-day use. A significant number of cycle paths were created in upstate New York, Denver, Minneapolis, Portland and California. In 1900, cyclists believed long-distance cycle paths would enable them to “go from New York to any point in Maine, Florida or California on smooth roads made especially for them.”

While bicycle-only paths were the fervent desire of many cyclists (to get away from pesky teamsters — the truck drivers of their day — and at least have a well-surfaced path, even if it was a narrow one), this desire was not shared by all — the building of bicycle-specific routes divided cyclists. There were arguments over whether or not the provision of paths diverted attention from the need to improve roads for all users.

Officials in the League of American Wheelmen (L.A.W.) were torn — some felt that their 20-year push for Good Roads had achieved little in the way of tangible improvements and that, despite a great deal of cajoling, it had been shown that farmers had no genuine interest in joining with them in demanding better highways; others believed victory was in sight and that to create bicycle-only routes would detract from the we-are-all-in-this-together message.

The widest and grandest path of them all — the Coney Island Cycle Path in New York — was loved by many cyclists, but not all. Some refused to ride on it, believing such dedicated routes, while superior to the rutted roads of the day, would become the only ways open to cyclists. They feared being restricted to a few recreational wheelways, and banned from all other roads.

Many in the broader Good Roads movement wanted cyclists to keep fighting to improve all roads, and not be diverted by improvements to just part of the highway.

However, an editorial in the L.A.W.’s house magazine in 1895 showed which way the wind was blowing: “The time is getting ripe for wheelmen to demand separate roads or cycle tracks of their own along the leading highways and such plans should be made and provided for in the new systems of roads which are being planned and built.”

Chief Consul Isaac B. Potter expressed a change in L.A.W. strategy in newspaper interviews and was condemned for it by many members of the organisation he led. An editorial in The New York Times in 1896 was also dismissive, hoping that Potter would “consider, on more mature reflection, that his suggestion was a mistake.”

For the wheelmen to seek provision of their own cycle paths would be a “public calamity,” thundered the newspaper, adding:

What is needed is to convince the rural public that good roads are economical, so economical that they cannot afford to have bad roads. Even if the wheelmen were to agree that, so long as a cinder path was provided for them, they would not object to the rest of the road being by turns a mud-wallow and a dust-heap, they would defeat their own purpose, for the full and combined force of all the elements enlisted in favor of good roads is necessary to produce good roads, and has not yet availed for that purpose.

Potter refused to budge. In a follow-up article, he wrote:

It is perhaps unfair to say that the public roads should be improved at great expense because bicyclists alone should seem to demand it, but it is not unreasonable to ask that a narrow wheelway should be improved at moderate expense on many country roads, which would otherwise be impassable to the great body of cyclists who have occasion to pass over them.

Perfecting just a slice of the public highway smacked of elitism, worried the Times:

More or less talk is now heard concerning special paths for cycling. Money is being raised, too, in some sections to cover the cost of building them — some by contributions, some by taxation the wheelmen only being levied upon for the necessary sums. [It] is doubted to be wise by many wheelmen to promote the building of pedal paths. It is better, they argue, to have good roads, which are a benefit alike to all classes, not to … merely those who ride bicycles … It has been the aim of the leading officials of the League of American Wheelmen to impress upon the minds of the members that no special path favors were desired, only good macadam roads …

That cyclists could one day find themselves confined exclusively to “their” part of the highway was felt by many to be a slippery slope, and for some, it was “class legislation,” a big no-no.

The author of an article on the “Gossip of the Cyclers” page in The New York Times — a weekly page in 1896 — reported that the construction of cycle paths was “assuming large proportions,” and that:

The wheelmen have for years been anxious to assist in the improvement of country highways, but since others who use the roads have not been as enthusiastic, the wheelmen have preferred to avoid further delays and secure what they might on their own account.

However, on the same page on the same day, the civil engineer General Roy Stone — who was not a wheelman — urged cyclists to stay within the wider Good Roads movement rather than go it alonThe general movement for improved highways in the State of New-York through the action of the existing legislative commission has taken such promising shape that I earnestly hope the influence of the wheelmen of the State will not be diverted in the direction of constructing separate cycle paths. Their help will be greatly needed in bringing about the general improvement of highways in the State, and such combined movement … will be of great value in its effect on the Legislature and upon public sentiment generally. If the bill for State aid which will be offered by the State legislative commission prevails, you will see many hundred miles of good roads built in the State of New-York …

This plea from General Stone went unheeded, in some quarters at least. Many cyclists had seen the future and it would be one of separation from the inferior road network, with superior provision for those riding bicycles.

Even the powers-that-be, it seemed, were often in favour of what detractors thought was pandering to pedallers. In 1895, Charles Schieren, the Mayor of Brooklyn, said:

… the cyclers rightfully demand good roads or paths for their accommodation. We must therefore plan additional facilities and build practicable roads for the exclusive use of the wheel … We must … set aside a portion of the roadway for the exclusive use of bicycles, or make additional paths for them … Good streets and roads will attract many people to a city or town which has them … Brooklyn is now seriously considering a plan for building a system of good roads and cycling paths … which will give from twenty to thirty miles of excellent paths to the lovers of the wheel, and will prove a great attraction.

In later years, cyclists demanded cycle paths as a form of protection from motor cars, and motorists were staunch supporters of cycle paths because this would remove cyclists from “motoring roads.” However, in the 1890s, those pushing for separate cycle paths were doing so to provide cyclists with a superior running surface.

Potter was not originally a supporter of cycle paths. He had long advocated “Good Roads for all.” His 1891 Gospel of Good Roads was a widely distributed L.A.W. pamphlet that demonstrated with data how good roads would benefit farmers economically. It encouraged them to join with cyclists to call for a radical overhaul of the antiquated system of building and maintaining roads. Conservative, stick-in-the-mud farmers, suffering from an agricultural depression in the early 1890s, would have no truck with radical ideas, especially those espoused by “them bicycle fellars.”

Most bristled at the idea of having to pay taxes to make good roads — at that time, they were still “paying” for roads with annual statute labour, a form of sweat equity. Farmers also feared that all-weather roads would be of most benefit to the urban elites on their recreational bicycles.

Potter despaired of this rural stubbornness and, by 1896, he was arguing in favour of cycle paths, in tandem with the provision of good roads. “I do not for a moment admit that this work for cycle paths can be substituted for the wheelman’s agitation for better roads,” he wrote, “but rather do I regard it as a valued auxiliary for the greater cause, which seems to have taken new impetuous [sic] in those sections where cycle paths have been put down.”

In 1898, Potter published Cycle Paths, an 86-page booklet which claimed that:

Every cyclepath is a protest against bad roads, a sort of public notice that the public wagon ways are unfit for public travel, a wit sharpener to every highway officer who has seven holes in his head, and a splendid example of the charming relations which the [bicycle] and the roadway may be made to sustain each other.

Potter wrote that cyclists paid “heavily to maintain a wasteful system of mere mudways and whose every effort for improvement is opposed by the ‘old settler,’“ — by which he meant farmers — “who insists that the road is good enough.” He added that the farmer was “not easily converted, and we may wait for centuries before he or his ilk will shout for better roads.”

Other wheelmen went further. “Why should the bicyclist carry the farmer like a millstone around his neck?” complained a cyclist in 1896, asking: “What has the farmer, the man most interested, done for good roads when left to himself?”

Another wrote:

… we gladly welcome every law which tends to give us better roads. But while we are waiting for the action of the State, and the County Board of Supervisors, and the farmers we are quietly building some good roads of our own, which we call “side paths” …

These sidepaths were to be examples to spread the Good Roads message, wrote Potter in Cycle Paths:

The bicycle path is a great object lesson for good roads and should be encouraged instead of frowned upon … It is a declaration of independence which for the time being lifts the bicycle out of the mud and puts the wheelman on a firmer ground of argument for good roads, takes from his critics the charge that the cyclist’s warfare is a selfish one and supplies to every traveller an impressive exhibition of the value of a good wheelway.

Before the building of cycle paths, cyclists had created short stretches of object lesson roads in towns and cities, with the L.A.W. advocating such methods from 1891. In 1894, the L.A.W.’s Sterling Elliott — editor of the organisation’s Good Roads magazine — was the first to push for the construction of short stretches of rural roads in order to “impress upon the farmer the value of such roads,” but it was the network of cycle paths in rural areas that were the first long-distance model roads. By 1897, the creation of “object lesson roads” had become the most important activity of the Office of Road Inquiry.

In its day, the Coney Island Cycle Path was the finest bicycle path in the world. Petitioned for from 1892 and finally built in 1894, it extended from Prospect Park in Brooklyn to the popular resort of Coney Island, a distance of 5½ miles. It added to the 1870s Ocean Boulevard, a “pleasure parkway” from “the City of Churches” to the Atlantic Ocean. Opened in mid-summer, the Cycle Path was an instant success — so successful that the path’s crushed limestone surface had to be repaired within a month of opening. A year later, three feet were added to the original width of 14 feet.

Those who owned stalls, rides and eateries at the Coney Island pleasure beach thrived from the increase in business brought by the cyclists following their “straight run to the sea.”

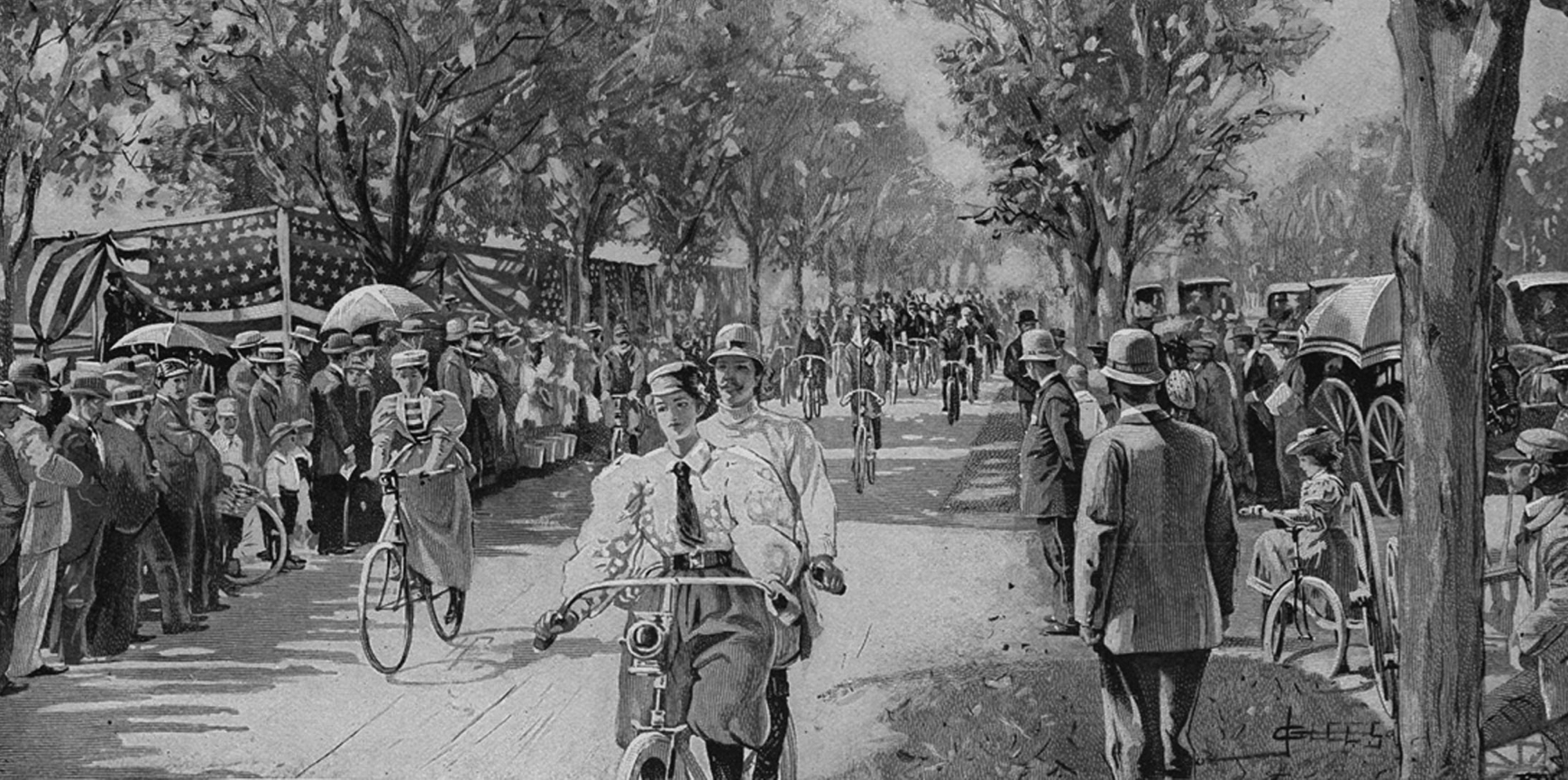

In June 1896, a return path was built on the opposite side of the boulevard. This was opened with a gala parade organised by the L.A.W., attended by 10,000 cyclists and upwards of 100,000 spectators.

The New York Times reported:

Attired in holiday garb and colors, the throng presented a picture pretty to look upon. That nearly every person in it was a cyclist or wanted to be was very apparent … Every public house on the boulevard was decked in flags and bunting, and many private residences were prettily decorated for the occasion … [a] juvenile rider had on a snow white Fauntleroy waist and red stockings with shoes to match. He was a cute little fellow, and somebody named him the ‘Red Spider’ … The bloomer girls received much attention, as usual. One plump lassie startled the reviewing stand with her green bloomers, but she didn’t mind.

The Coney Island Cycle Path was “for the exclusive use of the silent steed” — carriages used the macadam road, and equestrians were provided with a soft, sand path. The bike route was paid for in part by cyclists.

The L.A.W. paid $3,500 of the $50,000 necessary for its creation. Monies were raised by individual contributions, by newspaper campaigns (the Brooklyn Daily Eagle stumped up $50) and by fund-raising events such as theatre productions.

An appeal in The New York Times in August 1894 spelled out the advantages of cyclists part-paying for the proposed cycle path: “It is now within your power to have the most delightful and attractive wheelway ever provided for the exclusive use of cyclists: a smooth, clean continuous wheelway …”

The cycle path was “the first path in the world devoted exclusively to bicycles,” claimed the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, incorrectly.

“No wheelman who has ridden on it has complained, as the completed sections are so perfect that it is not possible to find fault with them,” continued the newspaper.

City authorities liked the path because it got cyclists off the road, away from pleasure carriages and horse-wagons. According to The New York Times, “the path is looked upon as an improvement [because] wheelmen do not interfere with driving at all, as the large driveway is now used exclusively by the lovers of horses and carriages.”

Brooklyn’s Transport Commissioner “had two roads constructed on the Ocean Parkway entrance so that the bicyclists may enter or leave the Park without danger of collision with vehicles … At the Plaza entrance, he has had Flatbush Avenue asphalted, so that the bicyclists may cross the [tram] tracks safely, and this path has been carried through one of the walks in Reservoir Point Park, so as to enable the bicyclists to reach the Eastern Parkway cycle path without danger.”

By and large, the Coney Island Cycle Path was for leisure rather than being a practical route, a point made snootily by Referee magazine in 1895:

Did you ever hear of the Coney Island Cycle Path? Never? Then you have not been in Brooklyn this season, for no cyclist can step his foot into that sleepy town and draw a full breath before he gets this shot at him: “Seen our Cycle Path? No? You should do so at once. Finest thing in the country. Just grand, sir; perfectly GRAND.” There is nothing like the Path. It is the favorite haunt of [the] boulevardier and is thronged each afternoon by crowds of these butterfly riders, who meander up and down its level stretches and call that cycling.

As Brooklyn had an estimated 80,000 cyclists it was perfectly natural to cater to the needs of a large, politicised and active group of citizens. With numbers, and the support of high society, creating bicycle infrastructure was a given. New York City’s Park Commissioner Timothy L. Woodruff was a wheelman. It was he who led the parade of 10,000 cyclists that celebrated the opening of the return Coney Island Cycle Path. In a speech to the cyclists, he said:

I am prepared, in my official position … to do everything within the limits of my powers as such to care for and advance the interests of the wheelmen of Brooklyn. I am anxious to do this not that I may cater to the comforts of a certain class of citizens, not because I am actuated by personal devotion to wheeling, but because I believe the safety bicycle is the most beneficial instrumentality of this wonderful age.

The cycle paths that came to national prominence in the late 1890s had been metaphorically built on the foundations laid by Charles T. Raymond of the canal city of Lockport, close to Niagara Falls, New York State.

“When our numbers were few, the road was good enough,” Raymond wrote in 1894, “but now our number is myriad and we need a road of our own which shall always be dry, smooth and hard, and may be used as comfortably in rainy weather as in dry.”

Raymond didn’t like the term “cycle path,” preferring “side path.” He had been the founder of the Niagara County Side Path League, founded in 1890, and which used club subscriptions to pay for short stretches of urban cycleways. (His organisation also received cash from the Pope Manufacturing Company and the Overman Wheel Company.) Raymond became convinced that cyclists would pay directly for improved rural paths, and he “adopted and promulgated the doctrine that ‘what all use, all should pay for.’”

Sidepaths were cheaper to build than improved roads — “Good sidepaths can be constructed at a cost of $100 to $300 per mile, while good roads cost from $2,000 to $5,000 per mile,” he wrote in 1898 — and “every mile we build makes the wheelmen hungry for more.”

In 1896 he helped to draft a county law allowing Niagara to tax bicycle owners and build cycle paths with the proceeds. Naturally, not all bicycle owners welcomed this general tax, and when there was a proposal for the tax to be extended state-wide, the Niagara chapter of the L.A.W. came out in opposition, urging “all wheelmen to strenuously oppose the passage of any such bills.”

Newspaper claims that the “sidepath movement” was “growing with irresistible momentum” were threatened when cyclists mustered to block further taxation on their activity. Cyclists in the city of Rochester in Monroe County, New York — “the greatest bicycle town in the country,” claimed the local newspaper in 1895 — argued against a tax on bicycle ownership. Urging the state governor to veto the bill, the editor of the Rochester Post Express railed against the “vicious principle” of “class taxation.” He wrote that “there is no more reason why the bicyclists should be taxed for cinder paths than that owners of vehicles should be taxed for the construction of better highways.”

Raymond pushed on and, following a sidepath convention held in Rochester in 1898, he helped to draft state legislation that encouraged localities nationwide to build cycle paths funded not by taxation on all cyclists but only on cycle-path users. New York’s General Sidepath Act of 1899 allowed a county judge, “upon the petition of fifty wheelmen of the county,” to appoint a commission of five people, “each of whom shall be a cyclist,” to represent the cities and towns of the county. These commissioners were “authorized to construct and maintain sidepaths along any public road, or street.”

Those cyclists who chose to use cycle paths had to attach “sidepath badges” to their bicycles. “Spotters” stationed themselves on cycle paths, checking which bicycles sported up-to-date “tags.”

Paying for cycling facilities was a familiar concept. Cyclists in Denver funded a 50-mile cycle path to Palmer Lake entirely by subscription. And in 1895, in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis—St. Paul, Minnesota, city workers built six miles of urban cycle paths paid for by cyclists, with the St. Paul Cycle Path Association stumping up the majority funding for another 14 miles of cycle paths in 1897 and 1898.

Payment for a cycle path “bicycle tag” was, in effect, an annual user fee and was to be the only money raised for building and maintaining cycle paths. Central Point, a small city in Jackson County, Oregon, passed a law in 1901 to construct “bicycle paths on either or both sides of all public highways of the state for the use of pedestrians and bicycles.” Cyclists — but not pedestrians — had to pay an annual tax of $1, for which they received a tag which, the law decreed, “must be securely fastened to the seat post of each and every bicycle.”

The “object and intent” of the law, the legislature said, was “to provide for a highway separate from that used by teams and wagons.” A similar law in Jacksonville, six miles from Central Point, said: “It is made unlawful for any person to ride a bicycle upon a bicycle path without having paid the license tax.”

This “provides a license for riding and [was] not a tax upon the bicycle.”

Portland, Oregon, had a turn-of-the-century network of 59 miles of six-foot-wide cycle paths, paid for by a cyclists’ user fee. Many American states had no legal mechanisms for raising taxes to pay for road improvements. Cycle-path taxes helped to usher in funding regimes that would be later used very successfully to raise money from motorists.

In 1949, an Oregon newspaper reminded readers that the “road tax” levied on cyclists was “the precedent for and the granddad of the present system of automotive licenses, gasoline taxes, fines and penalties which were established … and dedicated to the task of constructing the state highway system.”

However, there was a major difference, as revealed in 2012 by American historian Christopher W. Wells. He showed that the Interstate highway network was successful because of the invisibility of its financing, hiding the cost from end-users and not allowing the funds raised to be used for anything other than building yet more highways, a self-perpetuating system.

Not everybody was in favour of setting aside a portion of the public highway for bicyclists. Court cases in 1900 halted the construction of several cycle paths. In Spokane, Washington State, property owners secured injunctions against a proposed cycle path, claiming — as many anti-bike-path campaigners do today — that such a path would be “an obstruction of the street … that it shortens the width of a highway already none too wide … that it is a menace to children … and prevents owners of vehicles from reaching their conveyances with ease.”

Authorities countered by saying the path would be an “ornament to the street” and that the “path is desired by the thousands of wheelmen in the city.”

(4,000 of the 17,000 adult population of Spokane at the time were cyclists.)

A “wealthy resident of West Islip, [Long Island]” argued that the building of a cycle path in front of his house was “unconstitutional.” All of the court cases were lost, and county Sidepath Commissions felt emboldened to extend both urban and rural cycle paths. For two years there was a frenzy of cycle-path construction. Abbot Bassett, editor of L.A.W. Magazine and Good Roads, wrote in 1900 that cycle paths were “spreading with unexampled rapidity” and that they would form a “network of passageways for bicycle riders the continent over.” He asserted that “no other feature of cycling life … has a greater hold upon the hearts of American cyclists.” Cycle paths were the “very thing essential to their happiness,” and cycle paths “defeated bad roads in a manner not foreseen by those foes of progress who decried the cause of improved highways.”

While he admitted that cycle paths “[benefitted] none but wheelmen,” he wrote that it was “bosh” to claim that their provision amounted to “class legislation”:

When the first sidewalk was legally constructed, the law took into consideration a difference existing between pedestrians and [horse carriage] drivers … If pedestrians are by law entitled to a portion of the highway set aside for their exclusive use, why are wheelmen, when they exist in numbers sufficient for the law to take recognition of them, not entitled to a portion of the highway for their exclusive use?

Cycle paths were segregated both from the adjoining highway and from sidewalks, and were for bicycles only — other traffic could be fined for using them (and this use was tempting because cycle paths, while narrow, were far better surfaced than the adjoining roads).

Many cyclists — especially long-time riders, who were older and tended to be richer — were heartily in favour of cycle paths. They even had their own magazine, Sidepaths, published in Rochester, New York.

However, as localities quickly found out, not all cyclists took kindly to being charged for using cycle paths, and avoidance of the “bicycle tax” was rampant. Even if every cyclist in a town paid the annual $1 fee for a “bicycle tag,” this wasn’t enough to pay for a dense network of cycle paths or to maintain the existing ones.

When the town of Hoquiam in Washington State tried to prosecute a tag-free cyclist, the action was overturned by the state Supreme Court, with justices ruling that the “streets of the town are … public highways, common to all the citizens of the state,” and that access could not be denied to unlicensed cyclists.

Many bicycle advocates had long argued that local and national governments should fund infrastructure projects out of general taxation rather than user fees. Historian James Longhurst wrote that

… voluntary funding streams were insufficient for the construction and maintenance of serious infrastructure … Like roads, sewers and water works, the sidepath project required large-scale physical infrastructure demanding a steady and long-term investment. Voluntary funding was neither of these things. … Weak, partial funding for infrastructure might as well be no funding at all.

America’s most ambitious turn-of-the-century cycle infrastructure aimed to secure a more regular funding stream — the elevated California Cycle Way was a toll-road, barred to all but ticket-holders.

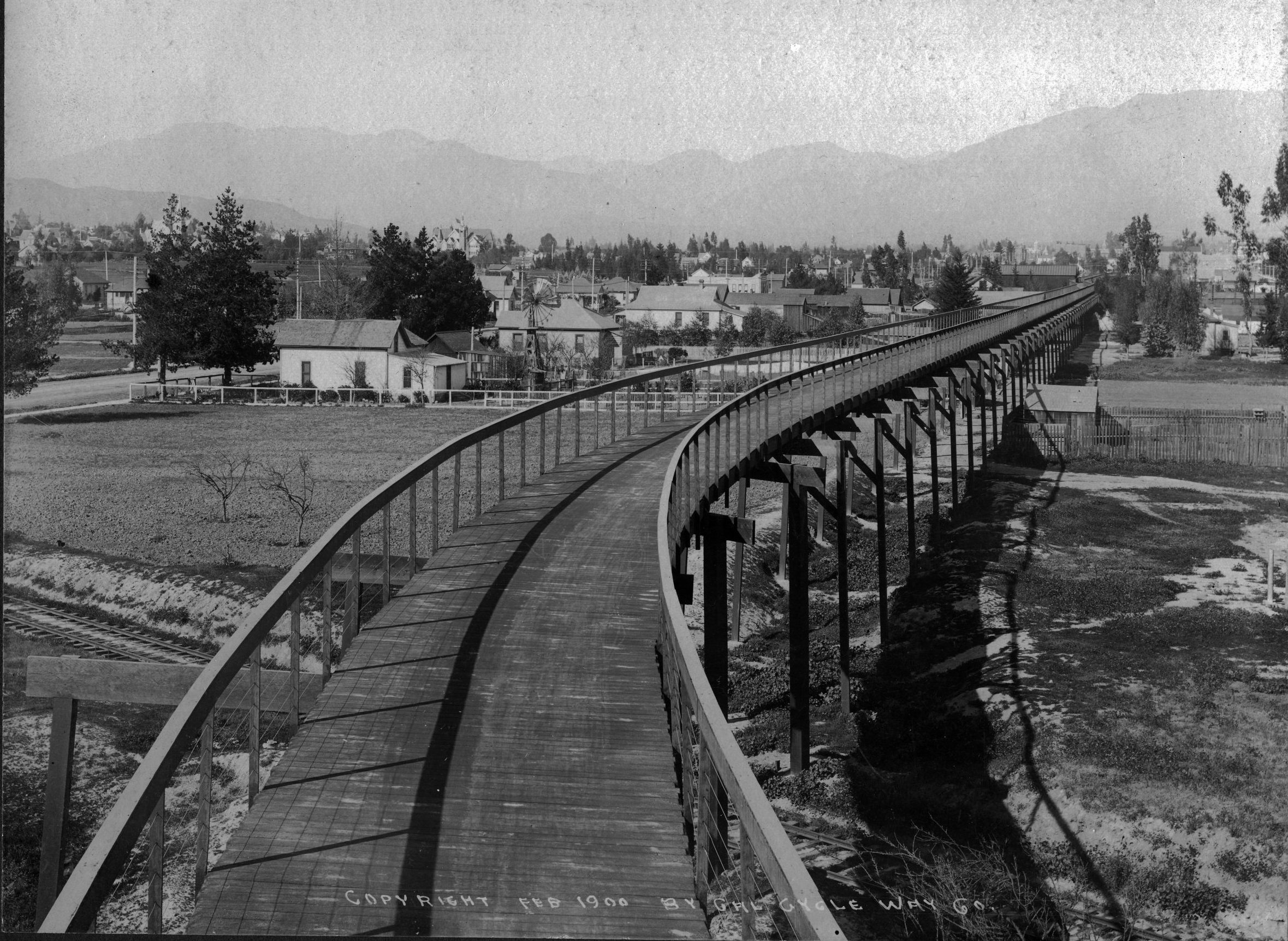

The first elevated highway between the cities of Pasadena and Los Angeles was built by one of the region’s richest residents, and paid for with tram-style journey tickets. In the first year of the 20th century this grade-separated highway towered over train tracks, road junctions and slow-poke users of the rutted roads beneath. The wooden trestle was billed as a “speedway” and was to provide a flat, fast scenic route for Pasadena’s thousands of cyclists, who could fly 50 feet high over the deepest section of the oak-studded Arroyo Seco river valley.

California Cycleway, 1900

The “ingenious scheme” was to be an uninterrupted “paradise for wheelmen.”

The reality for the California Cycle Way turned out to be far different. Only the first mile-and-a-bit was erected, which wasn’t long enough to attract sufficient paying customers. Within just months of opening, the cycleway had become a loss-making stub of a route rather than a profitable commuter cycling road for Pasadena’s wealthy cyclists. Had it been built to length the year after it was first proposed, the cycleway might have turned a profit, and could have become the “splendid nine-mile track” that, in 1901, Pearson’s Magazine (falsely) claimed it was.

Built with pine imported from Oregon, and painted green, the would-be superhighway had a lot going for it. For a start, it had high-society support: it was constructed for a company controlled by Horace Murrell Dobbins, Pasadena’s millionaire mayor, and the investors included a former governor of California, as well as Pasadena’s leading bicycle shop owner.

The California Cycle Way was first mooted in 1896. “The idea was originated by Horace Dobbins … who is himself a wheelman,” said the Los Angeles Herald.

The cycleway was meant to run for nine miles from the upmarket Hotel Green in Pasadena down to the centre of Los Angeles. The first 1¼-mile stretch opened to great fanfare on New Year’s Day, 1900, as part of the route of that year’s Tournament of the Roses Parade. Three hundred and fifty bicycles, decorated with floral displays, took part in the main parade and no doubt many of them were ridden down the wooden track by some of the 600 cyclists who took part in the cycleway’s inaugural ride.

In 1899, Scientific American called Dobbins’ plan an “elaborate wheelway” where “cyclists will … be permitted to view the beautiful scenery without having to look out for ruts in the road.”

The cycleway was wide enough for four cyclists to ride side by side, with another nine feet available alongside to plank another lane. This add-on was never needed: the cycleway was scuppered, in part thanks to rights-of-way objections lodged by a railroad magnate. Henry E. Huntington didn’t want speedy competition for his growing streetcar network. (The competition would be cheaper, too — a trolley car ride from Pasadena to downtown Los Angeles cost 25 cents, while the cycleway cost 10 cents one way and 15 cents for all-day use.)

Dobbins and Huntington’s Pacific Electric Railroad company would continue to fight over the rights-of-way for the cycleway long after the cycleway had ceased to exist as a route for cyclists. The California Cycle Way Company secured an injunction against plans for new lines from Pacific Electric and, in turn, Pacific Electric tried to condemn that part of the cycleway that it wanted to cross. It wasn’t until November 1902 that the two companies agreed to compromise.

By this time, cycling was on the wane in Pasadena and Los Angeles. The future, it seemed, was in fast public transit, with the building of streetcar lines the sensible thing for speculators to invest in.

A local newspaper reminisced in the 1950s: “Many Pasadena old-timers have happy memories of moonlight rides up and down that historic strip … the Cycleway was Pasadena’s pride and joy.”

Pride and joy it may have been but as a usable route it was short lived. By August 1900, a local newspaper reported the “Cycleway will do no more work now …”

Because the truncated cycleway wasn’t terribly long, didn’t go where people wanted to go and didn’t have enough entry and exit points, it was of little practical value, and hence not used and not profitable.

A built-to-length cycleway would have had an income of approximately $20,000 a month “if half of the wheelmen in two cities patronize the road once a month,” the company’s prospectus had claimed. Most of the period photographs of the cycleway show it empty. This wasn’t because there were no cyclists in Pasadena. The small city had 15 bicycle shops in 1900 and, according to the *Los Angeles Herald, in 1898 the city’s 9,000 residents owned 4,000 bicycles, with the Los Angeles area having “fully forty thousand bicycles.”

Pasadena’s many cyclists shunned the cycleway because its enforced short length made it more of a fairground attraction for hotel guests than a transportation option for locals.

Had the full nine miles been built in 1897, the cycleway would have been the quickest, slickest way to get from upper Pasadena to downtown Los Angeles (the plan was to also offer one-way rental of bicycles). Dobbins also imagined that it would be used at the weekend as a fast, flat way of getting from downtown Los Angeles to the foothills of the Sierra Madre and San Gabriel mountains.

The plans for the cycleway had been ambitious. The idea was for it to be grade-separated, to fly over the rutted dirt roads of the city and to soar over the Arroyo Seco river. Its incandescent lamps, at 50-foot intervals, would make the curving cycleway visible at night down in Los Angeles. There were also plans for the cycleway to snake past a lavish casino to be built in the Moorish style, complete with “a Swiss dairy … for the refreshment of the thirsty.” Neither the casino nor the Swiss dairy ever got off the drawing board.

Dobbins had begun acquiring the rights of way down the Arroyo Seco valley at the height of the bicycling boom in 1896. He incorporated the California Cycle Way Company on 23rd August 1897.

The company prospectus said that the route would be open to “bicycles or other horseless vehicles” (motor bicycles, rather than motor cars).

Dobbins was the company president and majority stockholder. Other investors included Henry Markham, who had been Governor of California two years previously; Ed Braley, owner of Pasadena’s biggest and oldest bike shop, the Braley Bicycle Emporium (now a Scientology church) and “Professor” Thaddeus Lowe, a Civil War balloonist who, in 1891, had helped create the Pasadena & Mount Wilson Railroad Company, which ran a steep-incline railway to the top of Mount Wilson.

From 1900 to 1901, Dobbins was chairman of Pasadena’s Board of Supervisors (precursor to the City Council — mayor in all but name, then) but, despite this leading role, and earlier elevated positions in the city’s administration, he had been initially unable to secure permission for his cycleway during the first year of his company’s incorporation. It took another city vote in 1898 before he got the required licence, a costly delay.

Erection of the structure didn’t start until November 1899. The Patton and Davies Lumber Company of Pasadena supplied the Oregon pine, and builders erected the first stretch of cycleway in just three months (grading cuts through the foothills had taken place in the preceding two years). On the first day of construction, the Pasadena Daily Evening Star said the “first section” of the cycleway would be “rushed to completion.”

The cycleway ran downhill from the luxurious Hotel Green, adjacent to the Sante Fe railroad station, to The Raymond, a resort hotel with its own nine-hole golf course. Pasadena was not yet friendly to “autocarists.” Arthur Raymond, owner of The Raymond, didn’t much like the first vacationing motorists. A sign outside his hotel read “Automobiles are positively not allowed on these grounds.”

Another sign outside the hotel pointed the way to the Dobbins’ Cycleway, which is how the route was known locally. To the outside world it was the Great California Cycleway and it was claimed to be a rip-roaring success. In September 1901 the mass-circulation Pearson’s Magazine devoted three pages to the cycleway.

“On this splendid track cyclists may now enjoy the very poetry of wheeling,” puffed T. D. Denham.

At Pasadena they may mount their cycles and sail down to Los Angeles without so much as touching the pedals, even though the gradient is extremely slight. The way lies for the most part along the east bank of the Arroyo Seco, giving a fine view of this wooded stream, and skirting the foot of the neighboring oak-covered hills. The surface is perfectly free from all dust and mud, and nervous cyclists find the track safer than the widest roads, for there are no horses to avoid, no trains or trolley-cars, no stray dogs or wandering children.

Denham claimed that “industrial activity will be so quickened [by this splendid track] that the country will enjoy such prosperity as it has never known.”

His article stated that the California Cycleway was nine miles long, as did most of the other press reports about the structure. Given that the cycleway had closed for business a year before, it’s rather strange that Pearson’s Magazine printed such a misleading piece — the magazine also reported as fact the supposed existence of the casino and the Swiss dairy.

Pearson’s wasn’t totally wrong — the cycleway did exist in September 1901 and it was probably still used. (The moonlight trips mentioned in the 1950s newspaper article may have been illicit rides — and dangerous, too: “A Mexican boy took hold of a live electric wire on the cycleway and received a shock which made him unconscious,” reported the Los Angeles Herald in 1906.)

In March 1901, a local newspaper reported that the cycleway was “to come down from Central Park tract” and that Dobbins “agrees to turn his franchise back to the city free of cost — to be paid only what that section of the structure cost.”

In October 1900, Dobbins told the Los Angeles Times: “I have concluded that we are a little ahead of time on this cycleway. Wheelmen have not evidenced enough interest in it …”

There are photos of the cycleway still standing in 1905, although by 1906 a newspaper said that it was “an eyesore to some people.” The following year, the Los Angeles Herald said the “old wooden trestle” was “objectionable” and that Dobbins had applied for it to be pulled down. Permission for the demolition wasn’t granted because the Board of Supervisors believed Dobbins “desires to use the old right of way for other purposes.” He did; he wanted to build a rail-road.

While at least parts of the structure may have been extant in 1919, most of it was pulled down in stages, and the lumber sold off. Some of those parts of the right of way owned by the city were used for a curving, scenic motor road. In December 1940, at the opening ceremony for the Arroyo Seco Parkway, Governor of California Culbert L. Olson declared it to be the “first freeway in the West.”

The 45-mph Parkway used short stretches of the former cycling route. Today, there’s a modern cycleway that follows some of the flood-control channels down the Arroyo Seco and this also uses a few short stretches of the Dobbins’ Cycleway route.

In 1958, Pasadena mayor Harrison R. Baker said that Dobbins was “way out in front of all of us” in dreaming up what would become, in part, the main asphalt route between Pasadena and Los Angeles.

An urban myth has since grown up around the California Cycleway. Newspapers and blogs claim that the cycleway was killed off by the motor car. “The horseless carriage … caused the demise of the bikeway,” wrote the Public Information Officer for the City of Pasadena on her blog in 2009. In 2005, a feature for the Pasadena Star News claimed that “Automobiles spelled doom for the cycleway.”

Numerous mentions of the cycleway have trotted out the same angle. In January 2014, the architecture correspondent for Britain’s Guardian even claimed that the structure, abandoned in 1900, was “destroyed by the rise of the Model T Ford,” a car not introduced until 1908.

There’s no proof that the advent of the automobile had anything whatsoever to do with the financial collapse of the cycleway. In 1900, motor cars were still fresh on the scene and very few people thought they had a certain future, and even fewer thought they had an all-dominant future. It was another 15 years before automobiles started to proliferate in the Los Angeles area.

Ironically, there’s a photograph from 1900 showing Dobbins on the cycleway in his steam-powered Locomobile motor car. He told the Los Angeles Times that “we will lie still for a time and use [the cycleway] for automobile service,” but this would have been 14 years too early and it would have also needed a great deal of modification. A short pleasure track for automobiles would have been just as pointless as a short hotel-to-hotel cycleway.

AUSTRALIA

“In Sydney,” reported a Scottish newspaper in March 1901, quoting the Sydney Morning Herald, “a Public Cycle Paths Committee has been successful in getting a ten-feet wide cinder path, nearly two miles length, laid down in Moore Park, one of the principal parks of the city, and the committee has now in hand … to have a cycle path ten miles in length formed on both sides of one of the best roads leading out of Sydney.”

According to the Spectator “in Sydney the cycle has its asphalted separate course,” stated an English newspaper also in 1901.

FRANCE

“The history of cycle paths in France … is little more than a series of hopes met with very few achievements,” complained a French cycle touring magazine in 1938.

“Before the [Great War], there were 1,180 kilometres of cycle paths on our territory. Their number was especially significant in the northern regions where the roads were paved. Everything was well maintained and the cyclists were satisfied with it. In short, this network was perfectly suited to the time when two million, eight hundred thousand cyclists were travelling, and when the number of motor cars was still insignificant. In short, it was more a question of convenience and comfort than a question of security.

“The problem today is no longer the same. On the one hand, the tracks were no longer maintained. Some even, like the famous Luzarches track, were broken up as soon as they were finished. Most are cut off by gutters, cluttered with materials or rubbish, in a word usable only on short sections.”

“On the other hand, the roads have been resurfaced using a new technique which has given our roads perfectly rolling surfaces. The result was that cyclists abandoned the cycle paths which had become impassable for the roadway, and often even declared themselves hostile to cycle paths in the face of the excellence of the roads.

“In the plan of major national works, which in 1935 provided for the creation of major highways, there was not once any mention of cycle paths.

“Just fragments of cycle paths are being built here such as on the National Road 10, between Paris and Rambouillet [near Chartres].”

“It is obvious that the cycle path will only really constitute progress in the traffic problem if it will offer cyclists as much comfort as security. Until recently, cycle paths were abandoned to their fate, and very quickly became rutted. Following complaints made to the Ministry of Public Works, it instructed Chief Engineers to better maintain the tracks laid out on the national roads.”

Despite the poor quality of French cycle tracks their use was mandatory, cheered a British motoring journalist. H. E. Symons, the Birmingham Daily Gazette’s motoring correspondent, wrote in 1936 that the “compulsory use of cycle-tracks has been introduced,” adding that on the “busy road from Fontainebleau onto Paris there is one rather narrow track on one side of the road only and at all intersections are newly erected discs warning cyclists that they must ride on the track.”

Recognising that this narrow track was inferior provision, Symons imagined that the “French cyclist would think himself in Heaven if he were given cycle tracks like those which Mr. Hore-Belisha provided alongside our newest by-passes: wide, well-surfaced and often available on both sides of the road.”

ITALY

“The development of cycle paths is recognized as necessary and around large cities work is being done to establish them,” reported a French cycle touring magazine in 1938.

SWEDEN

The modal share of bicycle traffic in Stockholm increased from 20 to over 30 percent during the 1930s, and reached higher levels during the Second World War, exceeding 70 percent.

Beginning in the late 1920s, bicycle lanes were established on some access roads to Stockholm.

In the 1936 Regional Plan for Greater Stockholm, the engineer Einar Nordendahl was dismissive of cyclists: “The construction of separate cycle and pedestrian lanes is largely motivated by the desire to free the road from such traffic elements that reduce both its traffic capacity and safety. This is particularly the case with the pedal cyclists.”

BELGIUM

The Touring Club of Belgium and the Belgian Cycling League were responsible for installing cycle paths in Belgium, according to a French cycle touring magazine in 1938. “The results are magnificent,” said the magazine. “Out of nine thousand kilometers of roads there are already nearly three thousand kilometers of cycle paths. Their width is just 1.5 m and their construction is excellent. The track is almost always separated from the roadway by a strip of around 50 cm which is generally grassed or covered with rolled stones.”

Since January 1936, “cyclists can no longer follow the roadway unless the public road is devoid of a cycle path or if the latter is impassable or congested,” noted the magazine. “In this case [cyclists] must line up at the far side and wait for the approach of another user!”

“In Belgium, out of the total road mileage of 5,500, 1, 800 miles (32%) are furnished with cycle tracks,” reported Britain’s Transport Advisory Council in 1938. Representatives of the body visited Belgium, and other countries, seeking information on cycle tracks.

SWITZERLAND

A French cycling magazine said that Switzerland “has recognized the need for cycle paths to reduce the number of accidents and has put the problem under study. However, implementation is not yet very advanced due to the difficulties encountered in widening the roadways.”

BRITAIN

The experimental two-and-a-quarter-mile “Track for Pedal Cyclists Only” retrofitted to London’s Western Avenue in 1934 was the first of the 102 such cycle tracks built in the 1930s and 1940s, but transport minister Oliver Stanley hadn’t been the first to call for such measures. Since the late 1890s, several other groups and individuals had called for similar infrastructure, at first to provide smoother ways for cyclists and only later to protect them from the growing numbers of motor cars on Britain’s roads.

British cyclists had started wobbling along Britain’s roads at the end of the 1860s. These riders, generally from the elite of society, didn’t require separation from the road traffic of the day because this road traffic, at least outside of cities, was light, sporadic, and generally far slower than the cyclists. Instead, the pioneer cyclists — on large wheel bicycles — essentially had Britain’s roads to themselves. So did those cyclists, including women cyclists, encouraged to take to cycling thanks to the introduction of the lower-to-the-ground Safety bicycle in 1885. For the best part of 30 years, cyclists ruled the road. This created in cyclists a feeling of ownership (and guardianship) of roads, helping to explain why the later motor-age imposition of separated cycle tracks rankled with many from “organised” cycling, especially touring cyclists who had travelled long distances on former turnpike roads that had fallen into disuse after the arrival of railways and the collapse of the stagecoach trade.

Similar to the impetus for “sidepaths” in the US, the first calls for British cycle tracks were for the amenity of cyclists.

In an 1897 article in the Christmas number of The Rambler, a weekly cycling magazine created by Daily Mail founder Alfred Harmsworth (who had been editor of Bicycling News in his youth), a writer asked, “Why Not Cycle Paths Everywhere?”:

Cycling is such an established institution now-a-days … that it is quite time something was done towards providing special bicycle paths on our roads … At present in this country there are over one million bicycles in use … Thus a greater proportion of persons ride bicycles than use carriages or ride on horseback … it is quite possible … to lay an asphalte strip on main roads for the exclusive use of cyclists …

A “strip” sounds rather narrow, while civil engineer Sir John Wolfe-Barry, the son of Houses of Parliament architect Sir Charles Barry, imagined a future with “bicycle roads.”

“No one who has lived in London can doubt that the pressure on the streets is getting yearly heavier and heavier, and becoming more and more unmanageable,” Wolfe-Barry said in a speech given at the Imperial Institute in Kensington in November 1898. Wolfe-Barry was speaking in his role as chairman of the Royal Society of Arts. His long speech, published as a pamphlet the following year, was one of many similar plans for fast-growing London, which was crippled by chronic congestion long before the motorcar.

In an obituary, it was reported that Wolfe-Barry, the person in charge of building London’s now famous Tower Bridge, had an “interest in traffic problems.” Sir John was “clear about two things: the immense pecuniary loss resulting from congestion and overcrowding, and the unwisdom of temporary makeshifts to alleviate those evils.”

What the 1918 obituary did not mention was that Wolfe-Barry’s congestion-busting proposal was for London to build wide arterial thoroughfares with separate “bicycle roads.” In his November 1898 address to the Royal Society of Arts, he used the word “bicycles” eighteen times. He mentioned motorcars not once. Motoring was still at the teething stage in Britain by 1898 and Wolfe-Barry clearly had little inkling that motorcars would soon clog the streets of London.

In his speech, Wolfe-Barry recognised that the building of London’s public transport network had done little to alleviate congestion. In fact, it had added to it as more people started to make more and more journeys, which had a knock-on effect once people exited the stations.

“My plea then,” urged Wolfe-Barry, “is that what is wanted to meet the requirements of the traffic of London is not so much additional railways, underground, or overground, traversing the town and connected with the suburbs, but rather wide arterial improvements of the streets themselves.”